Kamo kami

New Year arrow for good luck in the year of the dragon

Living next to a World Heritage site has its advantages, one of which is being able to pop across the road to make the first shrine visit of the new year. I did it rather late this year, on Jan 7, but there were still crowds of people and in front of the main shrine more than 100 in a long queue to pay their respects to the kami: legendary Kamo clan leader, Kamo no Taketsunomi, and his daughter, princess Tamayori. And thereby hangs a tale…

It’s said that Princess Tamayori (whose name means spirit caller i.e. a shamaness) was doing purification at the river one day when a red arrow came floating past. She picked it up, took it home and placed it by her as she slept (one variant has the arrow manifesting as a shining young prince). Lo and behold, she became pregnant and her child turned out to be a young prodigy, Wakeikazuchi. When asked one day about his father, he proclaimed that he was in fact a thunder deity and shot up into the sky. He is now enshrined at Kamigamo Shrine.

In one of the Shimogamo leaflets it explains the spiritual characteristics of their kami. Princess Tamayori, understandably, is a deity of childbirth and parenting. Her father, Kamo no Taketsunomi, is a guardian of Kyoto and by extension of the country as a whole. He also, oddly, is a kami of world peace, which makes one wonder why Emperor Komei in 1863 should have come here to pray that no foreigners be allowed to despoil the sacred soil of Japan.

Rice bundles donated by various companies

In shrine lore, Kamo no Taketsunomi is associated with yatagarasu, the three-legged crow of Japanese mythology (now used as a symbol for the Japan’s soccer team). The crow was an emissary of the sun-goddess sent to aid Emperor Jimmu as he battled his way across the Kii peninsula. My supposition is that a Kamo ancestor – a shaman of the crow clan – aided the Yamato invaders and that sometime later a descendant settled on Mikage hill in Kyoto’s eastern mountain range (Mikage shrine marks the site of his palace). The two figures were possibly conflated in the figure of Kamo no Taketsunomi – but that’s mere supposition.

Later it seems the family moved to the site of the present Shimogamo shrine, where princess Tamayori got herself pregnant. The early death of her son prompted the clan to deify him as a thunder deity, and a split in the Kamo clan led to the setting up of a new shrine in his honour at Kamigamo, followlng a vision that the thunder deity had landed on a stone altar (iwakura) Mt Koyama towards which the shrine is oriented.

(The above is simply my attempt at a literal reading of the mythology, so I hope no one will take it for historical fact. For one thing the priests at Kamigamo assert the primacy of their shrine and claim Shimogamo is an offshoot, so I may be getting myself in hot water!)

Changes

Shimogamo is noted for its antiquity, and no one knows for sure when the shrine was founded. It was here before the capital was established in 794, and remains from Jomon times have been found on the precincts. The pride of the shrine is a forest called Tadasu no mori mentioned in the Tale of Genji (c.1000) and supposedly a remnant of the original primeval forest that once filled the Kyoto basin.

I’ve been living next to the shrine for fifteen years now, and surprisingly there have been some dramatic changes during that time – including to the Tadasu woods. Replanting, path making and restoring an ancient waterway have meant constant activity. It seems every time I visit Shimogamo there’s an innovation of some kind, for the shrine is constantly striving to attract more visitors. It’s a reminder of how even the biggest shrines have to pay for themselves and earn their way.

In recent years I’ve noticed a number of improvements. More noticeboards with explanation and historical information. More leaflets and literature. There’s even a new pavilion for visitors to enjoy a green tea set. It’s said that large shrines like Shimogamo can earn enough for the whole year’s expenditure from the New Year period, so hatsumode (first visit of the year) is big business. It’s an opportunity too for folk to show off their finery…

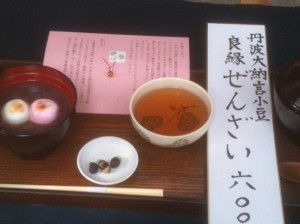

There's a nice tea set too to enjoy

The new tea pavilion in the grounds

Posing for a New Year pic before the torii

This time I made an interesting discovery in the woods, where a pathway has been cleared. Excavations have unearthed a small island shaped like a boat, dating from early Heian times. A noticeboard in English says that in shrine lore it’s known as the Heavenly Bird Boat and is thought to be where the kami descended. Ceremonies were held before it in the woods – nice! On one side is a well, which was the site of rain dancing rituals right up to the Edo period and pre-modern times.

Heavenly Bird Boat Island

The shrine’s currently undergoing its 34th cycle of the shikinen sengu rebuilding, which means buildings being temporarily out of action. The rite is carried out every 21 years, as at Ise, and is due for completion in 2013.

Only about ten shrines still keep to the practice, which originally meant complete rebuilding but at Shimogamo is limited now to repairs. It’s a fundamental part of Shinto’s belief in renewal and revitalisation, and it’s thought that the 21 year cycle is generational in allowing a new breed of craftsmen to learn from their predecessors in the many skilled jobs involved – nailless carpentry, thatching, weaving, etc.

Good connections

One feature the shrine has eagerly promoted since I moved into the area is the Aioi Jinja – a subshrine dedicated to ‘good connections’ (enmusubi). There’s been a boom in recent years for such shrines among young Japanese women, a demographic which is said to have the biggest surplus spending capital anywhere on earth. When I arrived fifteen years ago, the subshrine was in a poor state and pretty much neglected. Now it’s been nicely fenced, prettified with bell ropes, and a small walkway made around the ‘renri no sakaki‘ tree whose intertwined trunks are a symbol of conjugal devotion. I noticed that for the New Year there was an extra touch: flowers decorating the perimeter fence.

Praying for a 'good connection'

Colourful Genji-themed fortune slips

The shrine leaflet points out that prayers here need not be limited to the young, for parents can make requests of on behalf of their children. Nor need the ‘good connections’ be limited to love, for they could also affect other areas of life. But couples who are brought together by the kami in this way are welcomed to celebrate their wedding at Shimogamo – good business for the shrine.

Brightly coloured fortune slips have been made specially for the shrine with a Genji theme, since the Tadasu woods are mentioned in the novel. The colours mirror those of the elegant kimono worn by the aristocrats of those times, and each fortune slip is titled after a character in the book. Mine was no. 50 amongst the males and was named after Azumaya. Apparently if I’m patient, something or someone good is going to turn up, so it looks like I’ll have to bide my time.

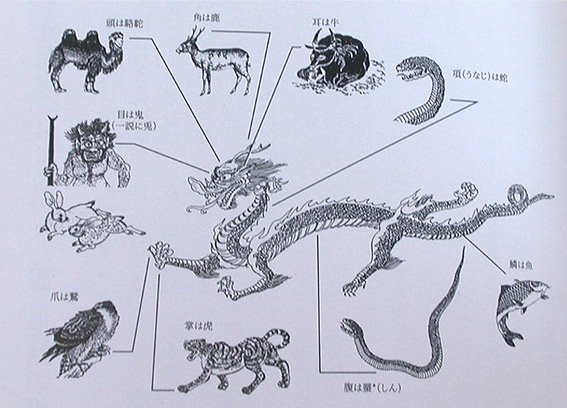

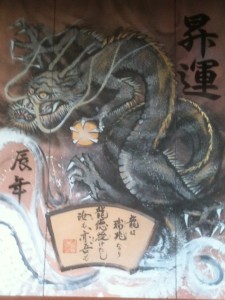

The shrine is doing its best in terms of outreach, even to those unable to visit the shrine for some reason. You can simply phone in your request and the priests will pray on your behalf and send you the relevant amulet. This time too I noticed quite a few extra goods in the shrine shop. Dragons were much in evidence of course, as well as the shrine’s motif of the aoi leaf after which its most famous festival is named. One popular motif is that of yatagarasu, the three legged crow associated with Kamo no Taketsunomi. All in all, this New Year, I got the impression things were flourishing at Shimogamo. Perhaps it bodes well for the year ahead…..

Tie for sale featuring the aoi leaf

Children's kite featuring a happy crow. Count the feet...

Large dragon ema board on display for the New Year

***********************************************************************************************

Both Shimogamo and Kamigamo have websites with some English information provided. Kamigamo also offers English-language tours and purification for visitors to the shrine.