Ou, what a relief

Susanoo slaying the eight-headed serpent

Ancient Izumo is a land of legends, associated with Susanoo and the slaying of the eight-headed monster (Yamata no Orochi). it’s also said to be the burial place of the mythological Izanami, who together with her spouse-brother Izanagi, created Japan. She was supposedly buried on Mt Hiba (near modern day Yasugi city), and when out of grief Izanagi visited her dead body, he was chased out by the Japanese equivalent of the Furies. Izanami is so closely associated with the area, that some say the name of Izumo is a nod in her direction.

Within the ancient province of Izumo lay the district of Ou, in which the city of Matsue now stands. Its peculiar name supposedly derives from the Land-Pulling Myth, in which a kami enlarged the province by pulling over some extra pieces of land from Korea. He marked the end of his exertions by striking a rod into the ground and letting out a long ‘Ou’ in relief.

In medieval times six of the area’s most prestigious shrines were formed into a pilgrimage group called the Ou Rokusha (Six shrines of Ou). Walking round the six shrines was popular in the Edo period for those looking to earn spiritual merit while taking a break from their usual routine. I’m not sure how long it took the hearty souls, but in a rented car it took me a little over half a day. Since it’s said the merit you earn is proportionate to the effort put in, i doubt I earned very much!

Entrance to Rokusho Shrine

The Ou Rokusha Mairi

Here are the six shrines. The first two are close together and definitely recommended. They’re not far from Matsue, one of Japan’s most attractive cities, and perfect for a short outing. The two shrines are both unique and charming in their own way.

1) Yaegaki Jinja (a Susanoo shrine). It’s said to stand on the wedding home of Susanoo and his bride, Princess Kushinada. It’s notable for its fertility symbols and an ancient pond which Kushinada used as a mirror and which is now used for fortune telling. For a full report, click here.

2) Kumaso Jinja (an Izanami shrine). The shrine is most notable for its striking architecture, which represents the oldest known example of the Izumo style. It’s a twenty-minute walk from Yaegaki and stands in a clearing up a steep step of stairs. The most atmospheric of shrines. it is in many ways the perfect example of how Shinto consecrates the spirit of place.

An unusual feature in the Kumaso precincts marks an opening in the hillside which once sheltered people taking refuge from persecution

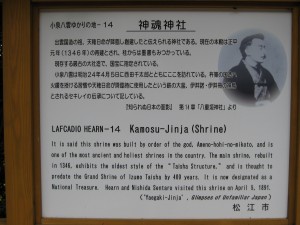

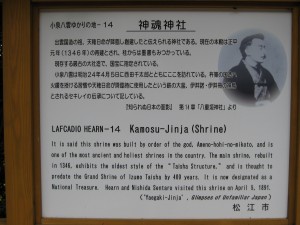

Hearn was here! The sole noticeboard at the Kumaso Shrine notes his visit in 1891.

Kumaso Jinja's distinctive architecture leading up to the honden main sanctuary where the kami resides

3) Rokusho Jinja (dedicated to six different kami, including the fractious Amaterasu-Susanoo siblings) Now a modest shrine in a small village, Rokusho once stood at the heart of the Izumo administrative machine. Behind the shrine is a field showing the site of huge tax-collecting buildings dating from the eighth century.

Steps leading to Manai Jinja

4) Manai Jinja (an Izanagi shrine). An unattended shrine up steep steps, which is associated with a waterfall on the hill behind. I had the feeling there was more to this shrine than meets the eye, for it is mentioned in the Izumo fudoki (chronicles written c. 733), but as yet I’ve been unable to find out much about it.

5) Kumano Taisha (a Susanoo shrine). The biggest of the six shrines, with tourist buses lined up and a tourist hotel set by the entrance. It was once not only the ichinomiya (top shrine) of Izumo, but is said to have been even more popular than the famed Izumo Taisha. It has claims to be the site of the wedding between Susanoo and Princess Kushinada. It’s also said to be the shrine were fire was first made for the gods, significant since Izanami was burnt to death while giving birth to the fire deity. But why on earth is it called Kumano Taisha, since the area of Kumano lies on the other side of the country altogether?

Kumano Taisha with its characteristic Izumo-style rice rope

I asked one of the priests about the name, and he told me that it used to be assumed that people from Kumano had brought their faith with them and set up shrine here. But recently there’s a new theory that people from Izumo had gone to Kumano, and then come back and set up a shrine in honour of the region. Presumably the ancient kingdoms of Izumo and Kumano were allied in ancient times, both of them overcome eventually by the emerging Yamato state. First Emperor Jimmu made his legendary march across the Kii peninsula, defeating the Kumano tribes he met on the way. Later Yamato was successful in pressuring the Izumo king into submitting.

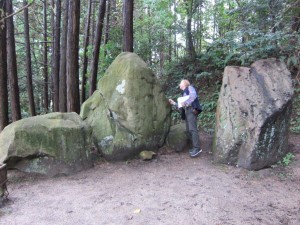

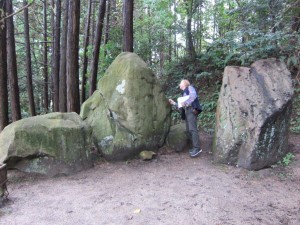

6) Iya Jinja (an Izanami shrine). Last of the six shrines I visited, appropriately, was the one known as Shrine of the Dead. it lies not far from a boulder with which Izanagi blocked up the entrance to the Land of Yomi where the putrefying Izanami lay buried. The boulder looks curiously ineffective, which is no doubt why hungry spirits continue to filter into this world.

The boulder with which Izanagi blocked up the entrance to Yomi and Izanami's tomb

There’s an eerie atmosphere at Iya Shrine, furthered by a reticent priest who appeared intent on not shedding any light on the shrine traditions. The shrine is mentioned in the Nihon shoki of 720 and I’d heard that the unusual banners to one side might represent something to do with Susanoo’s dragon. ‘Tabun,’ was all I could get out of the priest. Maybe he had a point: he who knows does not speak; he who speaks does not know, said the ancient sage. Mystery lies at the core of Shinto, and a sense of awe, reverence and wonder. Enough said!

The Iya Shrine sanctuary roof, showing chigi upright diagonals and katsuogi crossposts

The altar at Iya Jinja: simplicity itself

The peculiar rice rope structures in the grounds of Iya Shrine, representing the yamata no orochi serpent - perhaps

Iya Jinja worship hall with sanctuary behind, masked by trees

The sakaki branch is common in Shintō ceremonies. It’s used on altars, and it’s used as an offering to the kami. It’s used too as a vehicle into which the kami descends, and as a wand for purification. Performers hold sprigs in ritual dance, and it’s sometimes affixed to buildings or torii to signify the sacred quality. What is it exactly, and why should it be so sacred?

The sakaki branch is common in Shintō ceremonies. It’s used on altars, and it’s used as an offering to the kami. It’s used too as a vehicle into which the kami descends, and as a wand for purification. Performers hold sprigs in ritual dance, and it’s sometimes affixed to buildings or torii to signify the sacred quality. What is it exactly, and why should it be so sacred?