Approaching a realm of hills and mists; once a mighty 48 meter shrine might have been visible

When you approach Izumo Shrine these days, it’s along a busy road and past humdrum buildings. Once, however, the approach must have been breathtaking. Nestled against tree-covered slopes, there stood an enormous shrine whose dimensions dwarfed its surrounds.

Today the honden (inner sanctuary) is thought to be half the size of what it was in Heian times. Yet even now it remains formidable. In fact, size is what Izumo is all about. ‘It exudes masculine power, like the hunting lodge of some mountain giant,’ writes Jospeh Cali in the forthcoming Guide to Shinto Shrines.

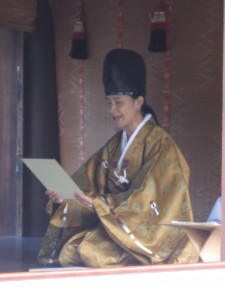

Unfortunately the honden cannot be seen at the moment as it is being rebuilt (for roughly the 25th time since the seventh century). It shows the emphasis Japanese put on continuity. Renewal and continuity. The present head, amazingly, is the 84th generation of the same Senge family who have run the shrine since its foundation. Hereditary succession says a lot about Japan’s conservatism and sense of an enduring self.

Like Ise, the honden here has a symbolic central pillar (shin no mihashira), reflecting the mythological pillar by which Japan’s creators Izanagi and Izanami descended from heaven. As in shamanism, spirits use the pillar to move between worlds. The cosmic connection is built into the fabric of the building.

Model of how Izumo might once have looked

Former shrine

There exists a tenth-century book called Kuchizusami, written to educate noblemen’s sons, which contains a reference to Izumo being higher than the massive 45-meter Todaiji Hall of the Great Buddha at Nara. Could it really be true? For years modern scholars speculated about the likelihood of such a building.

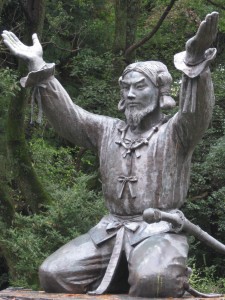

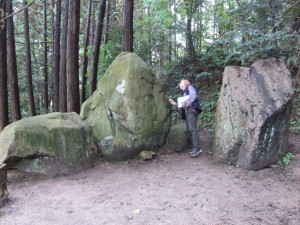

Clues to the possible construction came from a medieval draft held at Izumo, and experts came up with models of how the shrine might have looked Then in 2000 came an exciting discovery in the precincts of the shrine. Three huge cedar trunks were unearthed, which had been bound together to make one huge pillar. It was a vast three meters in diameter. The discovery caused huge excitement, because it showed that a huge shrine could well have existed in the past.

The present consensus is that the find dates from the 1248 construction, which was the last time the tall main shrine of ancient times was renewed. Thereafter circumstances led to the building of a lower shrine, with construction on a reduced scale during the medieval period and the fighting of the Warring States era.

Models of how Izumo’s honden may have looked before the middle ages, when it was the tallest wooden building in Japan, and possibly the world.

Glimpses of former glory

Inside the kaguraden, which copes easily with the masses of daytrippers

Reminders of Izumo’s former glory remain in the majesty of Izumo’s solid structures, such as the kaguraden. Unlike other shrines, this is not an open-sided stage, but a large building of such dimensions that whole busloads of tourists are swallowed whole.

The kaguraden boasts the world’s largest shimenawa (rice rope). It’s a massive affair that weighs five tons, so you want to be careful when standing below. At many shrines around the country, you find Japanese wanting to leave something for good luck – putting a stone on top of a torii is popular at some places. Here in Izumo there’s a tradition of throwing a coin up into the shimenawa. If it sticks, the gods will be happy and fortune will smile on you. I struck lucky with my first throw!

Izumo has pleasant and spacious grounds. Next door is the fascinating Shimane Museum of Izumo History, with the models pictured above as well as videos and explanations of the archaeological record. Fascinating stuff for those with a sense of curiosity about the past. Here at Izumo, history is encoded in the very structure of the place.

Izumo tree covered with fortune slips. This is the country's premier enmusubi shrine (good connections).

The shrine horse, messenger to the gods, getting a pat

Gaijin trying to get a coin to stick in the shimenawa

Reverence at one of Izumo's many subshrines. Who says the Japanese are not religious?

***************************************************************************************************

For an account of Izumo’s foundation, see Part One. For some stunning photos of Izumo Taisha, see ojisanjake’s blogspot.