The convivial discussion group I belong to meets monthly and discusses Japanese poetry in translation. Recently we’ve been looking at the eighth-century collection of poetry called Manyoshu, first of the great imperial anthologies. There are 4516 poems in all, some dating back as far as the fifth and sixth centuries. We’ve been focussing on the Best 100, which you can view for yourself. It’s rewarding stuff, and the conversations have been so rich we’ve only managed about ten short poems in two hours.

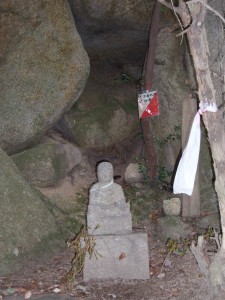

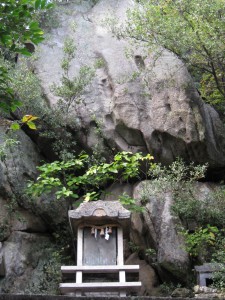

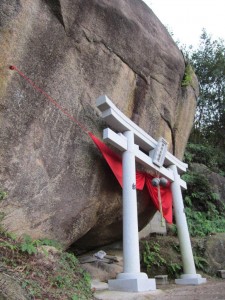

Amongst the Manoyshu verse can be found glimpses of the early religious sentiment of the Japanese. ‘Shinto’ as a concept was first used in the Nihon shoki of 720, to differentiate the native tradition from imported Buddhism. Before that there was a holy mess of differing cults and beliefs, comprising everything from fertility rites to shamanistic rituals and rock worship.

The Yamato basin showing one of its three hills

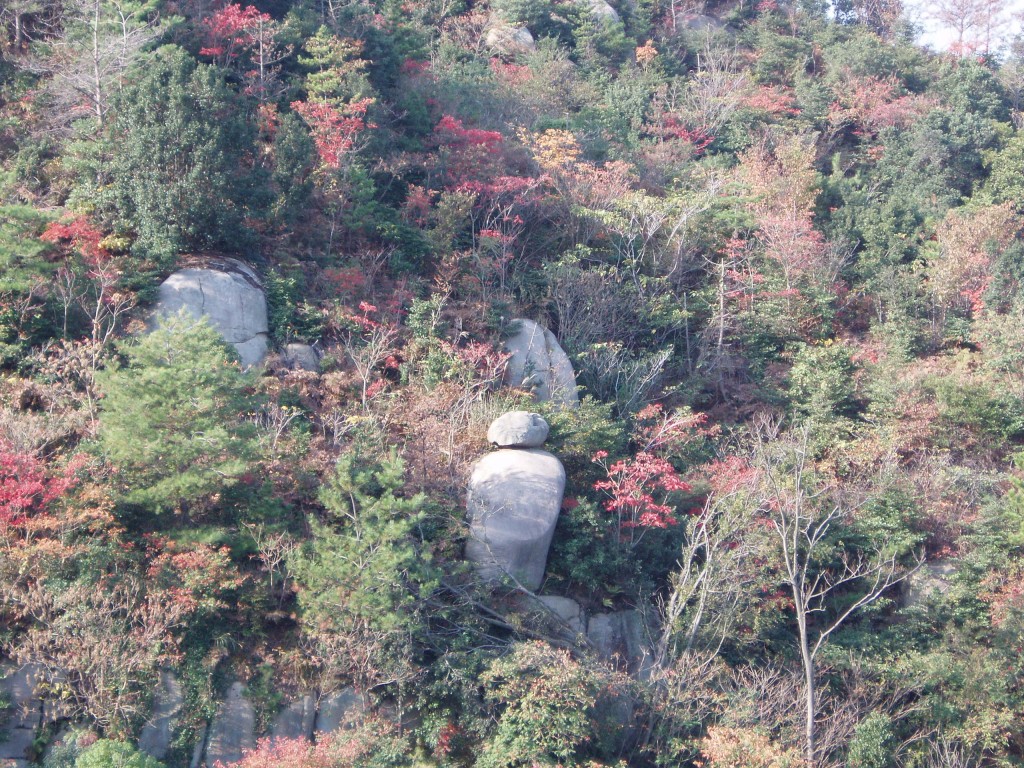

One of the most famous poems concerns the three hills of Yamato, the ancient heartland of Japan located near modern-day Nara. About five years ago I took part in an organised outing around the three hills, which made for a pleasant day’s hike full of historical associations. The walk finished at Mt Unebi, at the base of which Emperor Jimmu was supposedly buried and where Kashihara Jingu now stands.

In the poem the three hills are imagined to be in a love triangle, with two males vying for the hand of the female.

Mt Kagu strove with Mt Miminashi

For the love of Mt Unebi;

Such is love since the age of the gods;

As it was thus in the early days

So people strive for spouses even now.

Naomi Kawase, director of Hanezu

By one of those odd coincidences, I saw a film last week based on the poem. It was called Hanezu and featured a love triangle in present-day Yamato, where a young woman living with one man was having an affair with another. The film has a slow pace, voice-over rendition of the poem, and a rural lifestyle suggestive of unchanging ways and traditional patterns. It isn’t ‘a must-see film’, for the characters were not fully developed and the story unconvincing. It did give a sense though of the ancient poetry being embedded within the landscape, and within the Japanese soul.

Religious sentiments

But what of the proto-Shinto elements in the Manyoshu? There’s an interesting piece about this in the foreword to 1000 Poems from the Manyoshu written by Seichi Taki. He was writing at a time of State Shinto in 1940 and glosses his remarks with sycophantic imperial sentiments as one might expect. Nonetheless, he makes some key points.

The spirit of the sun, personified

1) The move from non-personfied to personified

At the beginning of the Manyo period (around the fourth and fifth centuries) there were various beliefs in non-personified mysterious powers, through natures spirits, to personified deities such as ancestral and tutelary beings.

With the rise to hegemony of the Yamato state, personified kami come to dominate. In other words, as the power of the emperor increased, so did the significance of Amaterasu and clan deities allied with the imperial cause. This encouraged the personification of nature and other spirits.

2) The will of the gods

The will of the kami made itself felt in a variety of ways, through dream, divination, oracles, omens, superstitions and the random acts of everyday life (such as being struck by bird droppings – there’s an amusing story of Abe no Seimei pondering the mess on the head of one unfortunate nobleman). Official divination, carried out by the Urabe clan, included deer shoulder and tortoise shell techniques, which from what I’ve gathered consisted of reading the cracks in them after they had been roasted, much like reading tea leaves.

One of the techniques particularly appeals to me: the Evening Oracle. This comprises going to a crossroads at dusk and listening to the snatches of conversation of passers-by. The words would contain hints as to the will of the kami. How very New Age! A Dark Age equivalent to the I Ching casting that was so popular in the 1960s…

As for omens, the coming of a lover was signalled by an itch in the eyebrow, a sneeze, or the girdle coming loose (!). One of the poems makes reference to the belief that thoughts of those at home are transmitted in some way to those travelling.

As I pass over Mt Shiotsu,

My horse stumbles;

Perhaps my dear ones at home

May be thinking of me.

3) Styles of worship

Worship was either in supplication or thanksgiving. The description Seichi Taki gives of “Manyo man” is oddly familiar and yet engaging in its directness and difference from the modern day…

“Generally in worshipping his god, he set in the earth before the altar a sacred jar filled with saké brewed with special rites of purification; hung up mirrors and beads on the sacred posts; tied his shoulders with a cord of yu fibre, presented the sacred nusa (purification wand) ‘with the sakaki branch fresh from the inmost hill’, and bending on his knees receited his litany (norito)… It was his ideal of life that he should keep himself clean in body and soul, and in constant communion with his gods, to obtain their protection and thereby live and work in a happy world. The Manyo man lived in a world peopled by multitudes of gods and spirits, genii and fairies.”

Next week I’ll be going to see that multitude of gods at the kamiari festival at Izumo on the Japan Sea. All of the country’s eight myriad kami gather there and are welcomed in an ancient rite held on a beach at dusk. It should be an exciting occasion. More of that anon….

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’