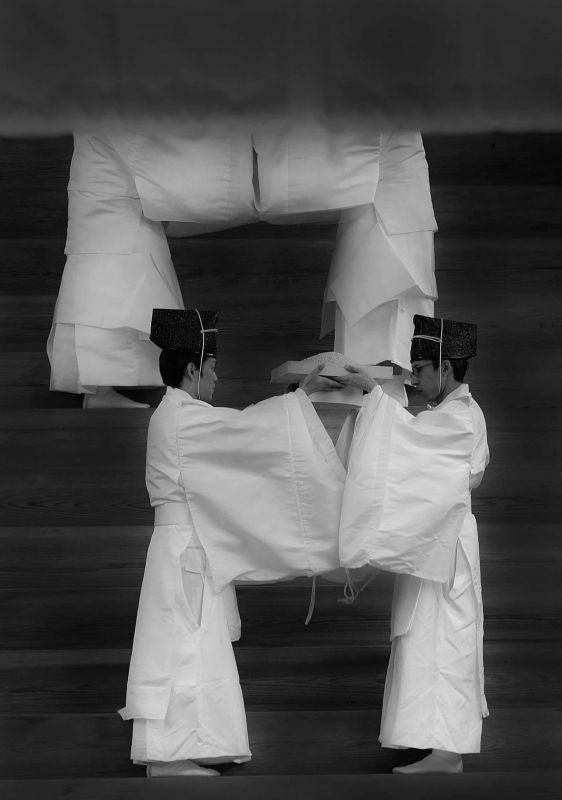

Ryuichi Kimura performs the shishimai (lion dance) at the Sanriku International Arts (Deck)

Ichikawa Kagura: Saving the dances of the gods

by Andrew Deck, Japan Times, Apr 21, 2019

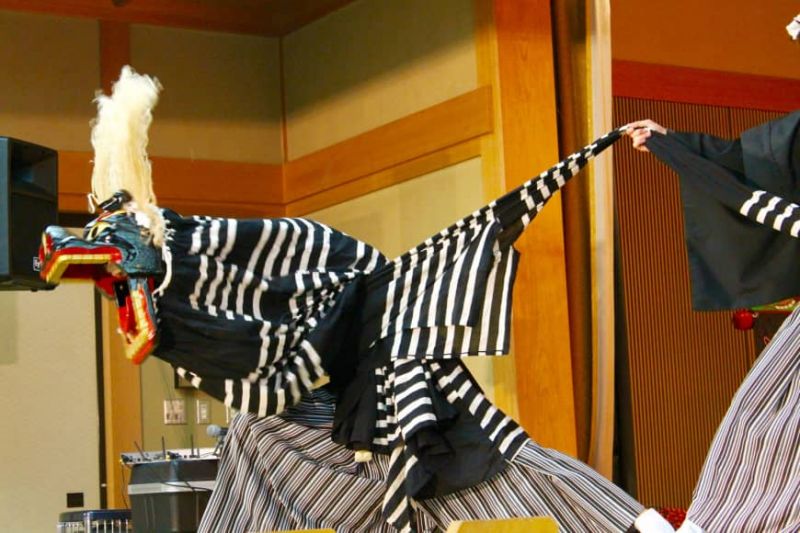

On his hands and knees, he bows toward a black lacquered mask baring menacing golden teeth, before standing and disappearing beneath an indigo-dyed cloth that drapes behind it. The shapeless textile suddenly takes on new dimensions, twisting and contorting theatrically as it becomes the body to the snapping jaws of the mask. Known as shishimai (lion dance), the performance involves a dancer wrapping his body in the cloth to embody the form of a wild animal.

Behind the mask is Ryuichi Kimura, a student of kagura (a type of Shinto theatrical dance) who has been training with the Ichikawa Kagura troupe since elementary school. At just 19, he is notably younger than his fellow members, the oldest having recently turned 93. The visible age disparity is not a coincidence — it illustrates a concerted effort by Ichikawa Kagura to pass on the traditions of one of Japan’s oldest and most endangered performing arts to a new generation.

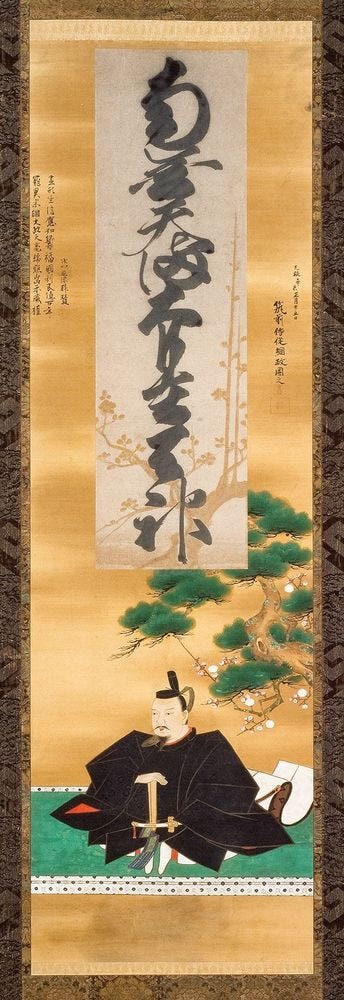

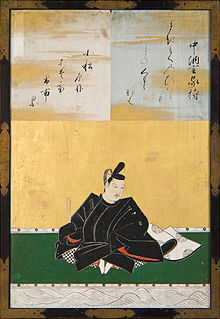

Miko dancing kagura at Kyoto’s Ebisu Jinja

Today, kagura is only practiced in small pockets throughout Japan, with local troupes keeping regionally specific variations alive. Shimane Prefecture and the city of Hiroshima are noteworthy hubs where the dance continues to thrive. Hachinohe, the home of Ichikawa Kagura, is a portside city in Honshu’s northernmost prefecture of Aomori.

The literal translation of “kagura” is “god entertainment,” and for over a millennium the Shinto theatrical style of dance has been practiced in Imperial courts, on shrine grounds and at seasonal festivals. Although kagura has evolved over the centuries, its earliest iterations predate the recognized staples of Japanese traditional performing arts, namely noh and kabuki.

In late February, visitors to Hachinohe’s frosted streets for the Sanriku International Arts Festival saw some of the prefecture’s best kagura — including Ichikawa Kagura’s shishimai. “The influence of Japanese culture is very strong now,” says Norikazu Sato, producer of the Sanriku International Arts Festival. “But many don’t know that there are forms of Japanese folk arts from ancient times that have been passed down for generations.”

With support from the Japan Foundation Asia Center, the festival organizes an annual showcase of regional folk performing arts with events held up and down the Sanriku coast, which encompasses Miyagi, Iwate and Aomori prefectures.

Founded by Sato in 2011, the festival’s original mission was to revitalize areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami through cultural projects.

“After we make a seawall, raise the soil, build new buildings and move forward with the tangible side of things, the next challenge is community in the disaster area,” says Sato. “Establishing a firm base of local culture and art makes it easier for local people to gather, to come together and also be stimulated by people visiting the region to experience that local culture and art.”

The festival has also helped elevate interest in regional kagura at a time when some of its performance styles are on the cusp of extinction. Largely an oral tradition, kagura relies on the minds and bodies of each troupe’s elder members. The Sanriku region, however, is not immune to Japan’s aging crisis and, as small Tohoku towns lose inhabitants to old age, local artforms like kagura are also at risk of dying out.

In 2017, an annual Iwate kagura festival was canceled when the lead dancer suffered a debilitating back injury. As the only performer who had learned by rote the required moves to perform the lead dance, his absence meant the town was left with no choice but to cancel the festival in its entirety.

That same year, a report by Kyodo News stated that 60 traditional festivals and dances — all designated intangible folk culture assets — had been canceled or postponed due to rural population decline.

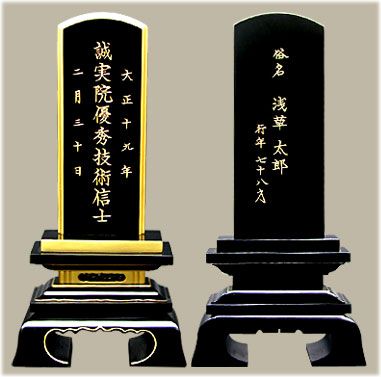

One of the masks used in kagura performances in the Shimane area

Backstage at a Sanriku International Arts Festival event, as elaborately costumed performers pass by in preparation for their moment onstage, Sato explains that during Japan’s prewar period there was a similar decline in the performance of regional folk dance, but that the erosion of regional traditions was later followed by a period of revival in the 1960s. Contemplating the future of kagura, Sato hopes for a similar trajectory.

“Perhaps there has been a decline in folk performing arts recently,” he says. “But if people remain within the art form, I think we will be able to resurrect it again.”

The burden of sustaining the traditions of regional kagura falls on the shoulders of young performers like Kimura, who was first introduced to the Ichikawa Kagura troupe as part of his recruitment program at Hachinohe’s Taga Elementary School.

Unlike most students, who dropped out in their middle school years, Kimura continued to study the art form throughout high school. Now at university, he still devotes time to kagura and his skills on stage are undeniable. Kimura seamlessly transitions between two traditional dance styles, one that includes dramatic spins of a fan with one hand, and another that requires his metamorphosis into the grizzly shishimai creature.

Kimura is also far from a passive member of Ichikawa Kagura. With the help of Ren Kimura and Kouma Izumi, two close friends who also joined Ichikawa Kagura in elementary school, Kimura was able to revive the troupe’s spring prayer ritual last year — a tradition that had been out of practice for more than 20 years.

By restoring the celebration, which entails hundreds of house-visit performances in Hachinohe, the younger generation brought back a small dose of kagura into the homes of the local community.

“Considering the age of our teachers, I feel that it will be up to us to maintain Ichikawa Kagura and make sure it doesn’t come to an end,” Kimura says following his performance, his two friends close to his side. “That is the future of kagura.”

*************

For a piece on the kagura origins of kabuki, see here.

For kagura at Takachiho, see this piece here.

The lion dance (shishi) comes in many guises depending on the region.

March 11, 2011 was a devastating day for Japan. Over 18,500 people perished in the gigantic tsunami that swept over the coastline of Tohoku in the country’s north-east. What’s more it led to a nuclear meltdown, the consequences of which are still on-going.

March 11, 2011 was a devastating day for Japan. Over 18,500 people perished in the gigantic tsunami that swept over the coastline of Tohoku in the country’s north-east. What’s more it led to a nuclear meltdown, the consequences of which are still on-going.

Every 60 years the stunning Izumo shrine buildings are reconstructed. Lafcadio Hearn called it the premier shrine in Japan, and it is thought to be even older than Ise. This is where all the kami of Japan gather every year, and there is a kind of dormitory where the myriad kami are put up.

Every 60 years the stunning Izumo shrine buildings are reconstructed. Lafcadio Hearn called it the premier shrine in Japan, and it is thought to be even older than Ise. This is where all the kami of Japan gather every year, and there is a kind of dormitory where the myriad kami are put up.