An Edo era picture of the kami of Japan gathered at Izumo for the kamiari celebration each autumn. How come they all gather at Izumo and not Ise?

“Depending on who speaks for or about it, Shinto may appear as an ancient folk tradition of personal prayers and communal festivals, as a nonreligious tradition of civic rites and moral orientations centered on the imperial house, or as a universal religion with ethical teachings.” – Jolyon B. Thomas in ‘Big Questions in the Study of Shinto’. Review of books for H-Japan, H-Net Reviews. November, 2017. The book discussed below by Yijang Zhong is entitled The Origin of Modern Shinto in Japan: The Vanquished Gods of Izumo (Bloomsbury Shinto Studies), 2016. ( Zhong is a professor at the University of Tokyo: see here.)

****************

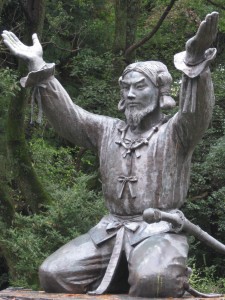

Okuninushi, lord of Izumo, whose legacy may have been usurped by the Yamato lineage

Jolyon B. Thomas writes…

Zhong’s new book persuasively shows that there are many stories to tell about Shinto, and not all of them would position Amaterasu, Ise, and the imperial household at the center of Japanese public life. Rather than focusing on the mythology that prioritizes the legitimacy of the imperial house, Zhong reads past this “official” Shinto to focus on the lineage dedicated to Ōkuninushi and the Izumo Shrine (located in present-day Shimane Prefecture).

Like Nancy K. Stalker’s work on Ōmotokyō as an “alternative Shinto” in Japan’s imperial period (Prophet Motive: Deguchi Onisaburō, Oomoto, and the Rise of New Religions in Imperial Japan [2008]), Zhong’s book shows that modern Shinto has never just been the official cult of the Japanese state. Zhong also shows that Izumo priests were able to successfully make the claim that Ōkuninushi was the only deity in Japan unambiguously associated with “pure” Shinto and not adulterated by Buddhist influence. This claim directly challenged the primacy of Ise and the imperial deity Amaterasu, who was still understood as a manifestation of the cosmic Buddhist deity Mahavairocana.

Zhong persuasively demonstrates in chapter 2 that it was Ōkuninushi, not Amaterasu, who received the lion’s share of popular attention during that time. This was based on a doctrine strategically generated by priestly lineages serving the shrine [in Edo Period} claiming that deities gathered at Izumo in the tenth lunar month to discuss marriages (en musubi). Their decision to conflate Ōkuninushi with the fortune deity Daikoku (one of the Seven Lucky Gods, or shichifukujin) also helped to boost the deity’s popularity, providing yet another challenge to Amaterasu’s authority.

Daikoku – conflated with Okuninushi because his name has the same Chinese characters

Chapter 3 in particular is an impressive argument that shows that modern Shinto came into being in response to external pressures and that National Learning (kokugaku) was inherently a response to the influx of Catholicism, Western astronomy and calendrical practices, and incursions from Russia to the north. Zhong focuses on the figure of Hirata Atsutane (1776–1843) and his 1811 book True Pillar of the Soul, which positioned Ōkuninushi as a cosmic deity with control over death and the afterlife; the book also rendered Shinto as a native epistemology that could hold its own in competition with foreign modes of knowledge.

In Atsutane’s rendering, Shinto became an indigenous tradition associated first and foremost with the terrestrial Ōkuninushi, while the solar deity Amaterasu assumed secondary status. Hirata’s disciples and Izumo priests rushed to disseminate the new doctrine throughout Japan even as political trends were shifting toward the “restoration” of the emperor to direct rule and the concomitant elevation of the imperial cult of Amaterasu. Despite his popularity, Ōkuninushi would eventually be eclipsed by the sun goddess.

*************

For a more in-depth review of the dissertation on which Professor Zhong’s book is based, please see this piece by Aike Rots.

For more about Izumo as an alternative centre of Shinto, see this previous posting.

Izumo Taisha, according to some site of the oldest shrine in Japan

The answer I was given by the friendly priest in the shrine office was that the calligraphy artist Yoshikawa Juichi had been asked to celebrate 160 years of Japanese-French friendship. (Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that the predominant colours are red, white and blue – colours of the French flag.)

The answer I was given by the friendly priest in the shrine office was that the calligraphy artist Yoshikawa Juichi had been asked to celebrate 160 years of Japanese-French friendship. (Eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that the predominant colours are red, white and blue – colours of the French flag.)

One of the most appealing aspects of Japan is the sanctification of history, so it’s interesting to see how a relatively recent episode like the introduction of rugby is being incorporated into the national past. In a board explaining the significance of the event, it said the shrine wished to show through the example of rugby how important it was to cultivate traditional ways. Traditional ways? And yet if one accepts that adoption and adaptation characterises the culture as a whole, then the statement makes sense….

One of the most appealing aspects of Japan is the sanctification of history, so it’s interesting to see how a relatively recent episode like the introduction of rugby is being incorporated into the national past. In a board explaining the significance of the event, it said the shrine wished to show through the example of rugby how important it was to cultivate traditional ways. Traditional ways? And yet if one accepts that adoption and adaptation characterises the culture as a whole, then the statement makes sense….