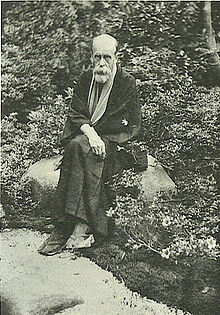

In the prewar years Shinto scholar Richard Ponsonby-Fane was much taken with the area and lived in an old Japanese house

The great scholar and eccentric, Richard Ponsonby Fane, was an interwar resident of Kyoto who turned himself into the foremost Shinto expert of his day – and that includes Japanese! It’s a remarkable achievement, all the more so when you consider he was an aristocrat who had forsaken a stately pile to come and live in Japan. He must have devoted all his leisure time to the mastery of contemporary and ancient Japanese while pursuing local and shrine history. (He had no need to work for a living.) He died shortly before WW2, though his private secretary Sato Yoshijiro continued to live in the city for long afterwards and to cherish his legacy. One person who knew Sato-san is woodblock artist Richard Steiner, and he has kindly written a report below for Green Shinto of the Ponsonby-Fane exhibition now showing at Shimogamo Shrine. (Part One of this two-part series featured family reminiscences of Ponsonby Fane by a descendant of Sato Yoshijiro’s brother.)

Ponsonby-Fane’s country seat in Somerset, England

Richard Steiner writes…

The exhibition house, a large, wooden, very well made, two-story traditional home originally belonged to one of the shrine families, the Itcho clan. It then became the home of one of Kyoto’s mayors, and lastly the home/studio of a well-known Nihonga painter. The shrine got the property, had it preserved and modernized inside while keeping the wood and doors and windows and garden all in working condition. The building is located on the south bank of the Izumi-gawa river (where river means trickle). A magnificent job.The house has many small rooms; Ponsonby’s exhibition occupies two and a half of them, in different parts of the first floor (second floor is closed). On display are lots of documents in English and Japanese, letters, books in Western and Japanese bindings, personal items of Ponsonby’s, one great photograph of him surrounded by the Sato-clan, a stone rubbing and a color photograph of his memorial stone at Kamigamo Shrine, and more. There are also the six published books of Ponsonby’s, the second, red binding edition, sitting on a window sill: (I have the first edition, a blue bound set, which I bought directly from Sato Yoshijiro).All of this life-work is really smartly displayed, thanks to exhibition organiser, Araki san (the young son of Shimogamo Shrine’s present chief priest). We also met Mr Hiyama, a cousin of the Sato’s, who lived in the Sato house until they all passed away, and, ergo, became the keeper of Everything Ponsonby. .He understands this position and honors it completely.This exhibition is the first instalment, with plans for another to be set up after September with interesting material, which is being attended to at present.

The house near Kamigamo Shrine where Ponsonby Fane lived, now taken over by a company