Yoko Makino, talking of Hearn’s view of the kami

‘Japan, the Land of the Kami as Perceived by Lafcadio Hearn’ was the title of the Lecture Event put on at Meiji Jingu to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Irish-Japanese diplomatic relations. The Japanese for the event was ‘Koizumi Yakumo no mita kami no kuni, nippon’. The use of the Japanese name for Hearn seems to suggest the country has taken him to heart as one of their own. The second of the two talks served to confirm that.

Yoko Makino, professor of Seijo Univesity (Faculty of Economics), is a former pupil of Sukehiro Hirakawa, and her talk was titled ‘The Image of Shinto Shrines in the Works of Lafcadio Hearn’. The theme was that he had better understood the appeal of Shinto than his illustrious contemporaries, B.H. Chamberlain, William Aston and Ernest Satow.

For foreign scholars, Shinto was intellectually void for it lacked dogma, doctrine and ideology. Not only was nature worship regarded as primitive, but the shrines were seen in terms of plain wood with little artistic merit whereas Buddhist temples with their cosmology and ornate decorations were worthy of high respect. Chamberlain even quoted with approval the comment of one visitor to Ise Jingu who complained they had nothing to show and made a great deal of fuss about showing it.

Shinto, so often spoken of as a religion, is hardly entitled to that name… It has no set of dogmas, no sacred book, mo moral code.

Hearn by contrast was a Romanticist, more concerned with feelings. His explicit aim was to see into ‘the heart of the Japanese’, to which end he intended to live among Japanese as if one of them. In this way he came to a sympathetic understanding of Shinto, remarkable for his age (he wrote at a time when Western values were automatically assumed to be superior).

Yet something of what Shinto signifies… may be learned during a residence of some years among the people, by one who lives their life and adopts their manners and customs. With such experience he can at least claim the right to express his own conception of Shinto. (from ‘Household Shrines’)

Lafcadio Hearn’s image on a shop front in Matsue, indicative of his place in Japanese society

Makino illustrated her point with three passages from Hearn that showed how deep was his appreciation of indigenous practice. These consisted of 1) the approach to the shrine; 2) the shrine building; 3) the kami inside the shrine. With their setting on hillsides and in sacred groves, the locations of shrines are often as striking as they are appealing, something for which Hearn showed great awareness.

Of all peculiarly beautiful things in Japan, the most beautiful are the approaches to high places of worship or of rest, – the Ways that go to Nowhere and the Steps that lead to Nothing… Perhaps the ascent begins with a sloping paved avenue, half a mile long, lined with giant trees. Stone monsters guard the way at regular intervals. Then you come to some great flight of steps ascending through green gloom to a terrace umbraged by older and vaster trees: and other steps from thence lead to other terraces, all in shadow.

Hearn goes on to describe the architecture in remarkable detail, commenting on how there is no artificial colour but plain wood which turns under the influence of rain and sunshine to a natural grey ‘varying according to surface exposure from the silvery tone of birch bark to the sombre grey of basalt.’ He then writes of the ‘august house’ of the kami as a haunted room, a spirit chamber, in which live ancestral ghosts. [See here for his writing on ghost-houses.]

There are three beliefs which underline ancestral worship, he says, whether in Japan or elsewhere. 1) The dead remain in this world. 2) All the dead become gods (in that they have supernatural power). 3) The happiness of the dead depends on the respectful service of the living.

Imagining the kami

Hearn’s ability to enter imaginatively into the world of the Other was nicely brought out by Makino in a passage from Hearn’s ‘A Living God’, in which he wonders what it would be like to be a kami, guarded by stone lions and shadowed by a holy grove. He would have no form or shape, but like a natural vibration he could pass through walls ‘to swim in the long god bath of a sunbeam, to thrill in the heart of a flower, to ride on the neck of a dragonfly’. Here, the speaker interjected, Hearn was clearly reaching back to the fairy folklore of his youth, yet in his description of the interplay of worshipper and kami Hearn was able to summon up the essence of Shinto in unparalleled manner.

From the dusk of my ghost-house I should look for the coming of sandaled feet, and watch brown supple fingers weaving to my bars the knotted papers which are records of vows, and observe the motion of the lips of my worshipers making prayer…

Sometime a girl would whisper all her heart to me: ‘Maiden of eighteen years, I am loved by a youth of twenty. He is good; he is true; but poverty is with us, and the path of our love is dark. Aid us with thy great divine pity! – help us that we may become united, O Daimyojin!’ then to the bars of my shrine she would hang a thick soft tress of hair, – her own hair, glossy and black as the wing of the crow, and bound with a cord of mulberry-paper. And in the fragrance of that offering, – the simple fragrance of her peasant youth, – I, the ghost and god, should find again the feelings of the years when I was man and lover….

Between the trunks of the cedars and pines, between the jointed columns of the bamboos, I should oversee, season after season, the changes of the colors of the valley: the falling of the snow of winter and the falling of the snow of cherry-flowers; the lilac spread of the miyakobana; the blazing yellow of the natané; the sky-blue mirrored in flooded levels, – levels dotted with the moon-shaped hats of the toiling people who would love me; and at last the pure and tender green of the growing rice.

The muku-birds and the uguisu would fill the shadows of my grove with ripplings and purlings of melody; – the bell-insects, the crickets, and the seven marvelous cicadae of summer would make all the wood of my ghost-house thrill to their musical storms. Betimes I should enter, like an ecstasy, into the tiny lives of them, to quicken the joy of their clamor, to magnify the sonority of their song.’

In this way, nourished by the devotion of worshippers, the kami participates in human life and the seasonal cycle. In a superlative flight of fancy, Hearn has the kami transcend its ghost-house to enter into bird-bodies and become the very voice of nature. Here in imaginative form is the essential spirit of Shinto, and for anyone who doubted the genius of Hearn the brilliance of the writing is surely more than sufficient proof. Like all visionaries, he was a man of extraordinary insight and a hundred years ahead of his time.

******************

For Part One about the lecture by Sukehiro Hirakawa, please see here.

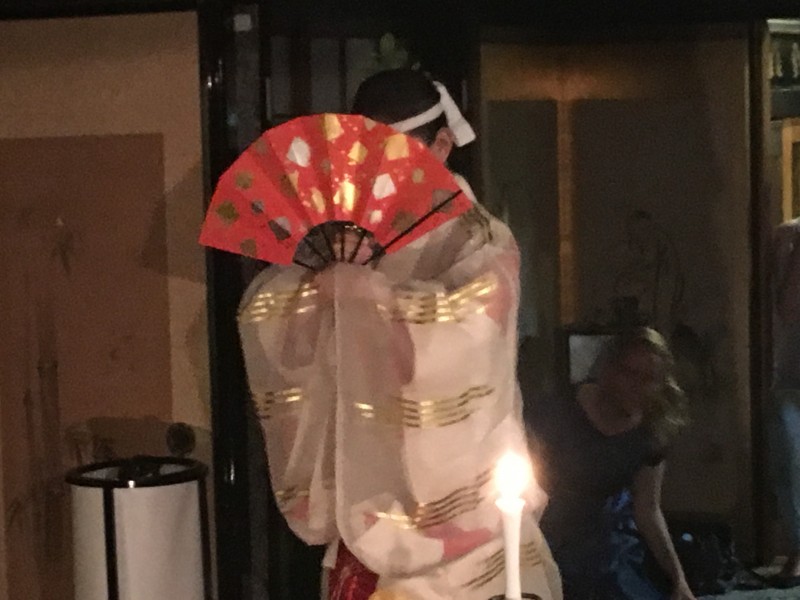

Yoko Makino talking on the Image of Shinto Shrines in the writings of Lafcadio Hearn with particular reference to his essay on ‘A Living God’