This is part 22 of a series following a three-month journey the length of Japan, beginning in northern Hokkaido and finishing in the south of Kyushu. This extract from a forthcoming book concerns Fukuoka, which in the form of Hakata Bay was invaded by the Mongols twice, once in 1274 and the second time in 1281.

*******************

For the Japanese, the invasions mark as glorious a victory as the Spanish Armada of 1588 for the English. In both cases an island country was attacked by the most powerful continental force and secured an unlikely victory, leading to an upsurge in national pride. And in both countries the victory was aided by the weather, fuelling the notion that the countries were divinely blessed.

In Japan’s case, the invasion was initiated by the formidable Kublai Khan, who demanded the country become a vassal state. When this was refused, he put together a large force which overwhelmed the outnumbered Japanese and burnt down Hakata Town. The samurai were skilled in single combat, but the attackers used hand-thrown bombs and huddled together in a tight-knit group. Just when it seemed all was lost for the Japanese, a timely storm destroyed some 200 Mongol ships and the invaders fled home.

For their next attempt, the Mongols amassed a much larger force, estimated at 1500 ships and some 70,000 soldiers. This time the Japanese were better prepared and prevented the Mongol army from taking control of the mainland. Instead the invaders set up base on an offshore island. Fighting was more or less at a stalemate when a typhoon intervened. In the chaos that followed, hundreds of ships collided or sank, and over half the invasion force perished. For the victorious Japanese it was proof that the gods were on their side, thanks to what they dubbed kamikaze – divine wind.

There remain some physical reminders of the events even now, centuries later, such as decaying defensive walls and look-out spots. Hakozaki Shrine, razed in the first invasion and rebuilt by the time of the second, still acts as a locus for thanks-giving and bears an intimidating slogan on its tower gate: Tekikoku Koufuku – Submission of Enemy Countries. This is Shinto in its guise of national rather than nature religion.

To get a feel of the past, Hirota san and I headed for Higashi Park, which was the site of fighting in the first invasion. It hosts a Mongolian Invasion Museum in which are shields worn by the two sides, as well as armour made of hardened animal skin. ‘It is said the Mongolians were very cruel,’ said Hirota san. ‘I saw a programme with Marco Polo.’

‘Marco Polo?’ I said in surprise. ‘What did he have to do with the invasion?’

‘They said he was involved in the negotiations.’

‘Really? That must be fiction, surely’

‘Maybe. It was NHK drama, because Marco Polo brought a Japanese to meet Kublai Khan’s son. And there is a manga based on history. Angolmois: Record of Mongol Invasion. It was very popular, so it became anime on television.’

In the middle of the park stood a bronze statue of Emperor Kameyama in an exaggeratedly tall eboshi, the black-lacquered hat worn by aristocrats.’ He was retired, but he kept power,’ said Hirota san. ‘The length of the hat shows masculinity,’ he added. A signboard noted that in a prayer at the time of the invasion the retired emperor had offered his own life in return for peace.

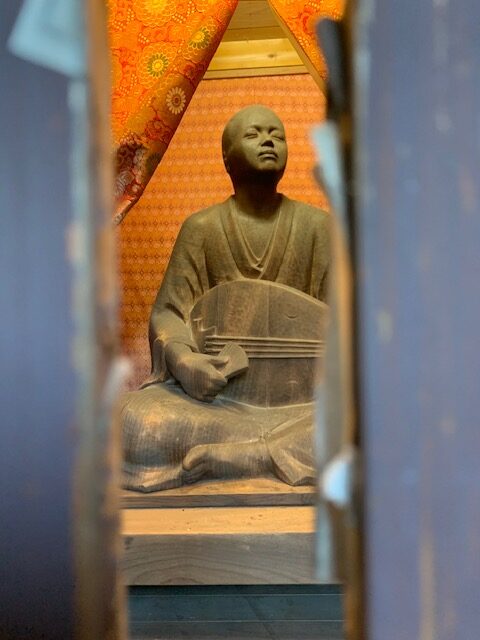

To my surprise the park hosted a much larger statue for Nichiren. Bigger than the emperor; what was that about? His belief in the supremacy of the Lotus Sutra had led him to denigrate ‘false prophets’ who thought differently to himself, and he ascribed to them all the ills of the country. As a result he predicted Japan would be invaded, and when the Mongols appeared it seemed to validate his teaching. For the Buddhist Nichiren, you could say the kamikaze was doubly divine – not only heaven sent, but testimony to the truth of his preaching.