A pair of Meoto rocks at Nobeno Jinja

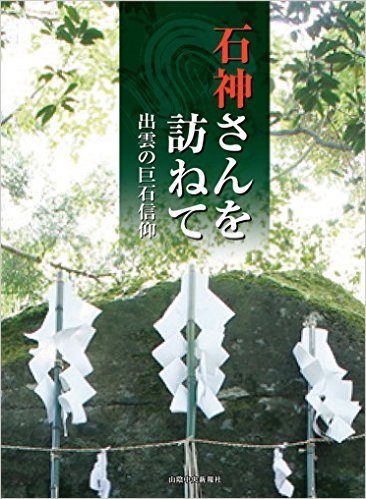

I happened to come across a Japanese book the other day that very much took my fancy. It was called Ishigami san o tazunete (Visiting Stone Kami) and was produced by the editorial staff of a local publisher in the Matsue area, Sanin Chuo Shinposha. It featured photographs of Shimane Prefecture’s sacred rocks together with an introduction by ‘Big Rock Hunter’ Suda Gunji.

It seems that Suda Gunji shares my own fascination with sacred rocks. Even before coming to Japan, I was fascinated by the standing stones of the Avebury stone circle and pondered what had driven ancient Britons to move these megaliths such long distances. For me, sacred rocks are the heart of Shinto, yet they are sorely overlooked by the post-Meiji fixation with emperors and imperial ancestors. Some apparently see the rocks as belonging to an ancient and mysterious past which is no longer relevant. The downplaying (even removal) of phallic and vulvic rocks is a classic example. By contrast contemporary Shinto emphasises the ancestral side of the religion.

Big rocks impress, they don’t change or age like humans, says Suda Gunji in his introduction. We respect them because of their monumental nature. He then goes on to identify four basic types:

- those with myths attached to them

- those that formed the origin of a shrine

- those into which kami descended

- those with a special shape that became part of local folklore

Personally this strikes me as a rather strange classification system. There are after all plenty of rocks into which kami descended which then became the origin of shrines. There are rocks with myths about kami descending into them, and there are rocks with a special shape to which myths accrue. In short, many if not most rocks fall into more than one of the groups. Rather than shedding light the classification seems rather to create false borders.

The book contains a map of Shimane Prefecture showing the sites of some hundred special rocks. I’ve always been impressed by the number of sacred rocks along the Inland Sea coast, seeing them as the legacy of Korean shamanism spread by traders and emigrants on the main trading route between the continent and the seat of the Japanese government. The prevalence of sacred rocks in the Shimane area may be due to a similar link with Korean shamanism in the Silla origins of the Izumo clan.

Of the 100 sacred rocks in Shimane, Suda Gunji has inspected 44 of them (he’s been photographing rocks for over 20 years). He can sense the energy given off by rocks, and the most powerful he’s come across is Izumo-shi Tateishi Jinja (Standing Rock Shrine in Izumo City). It stands in a forest amidst a group of rocks, the entrance to which is marked by gohei. It reminded him of an Okinawan utaki, he writes. Since the shrine is for a rain god, it gives him a sense of antiqueness, as if stretching back to the primitive rain practices of Jomon times.

Modern people think rocks are silent, notes Suda Gunji, but Norito prayers from the past show that people in ancient times had a sense of them talking. Native Americans also think rocks communicate spiritual power (interestingly, they may have been racially and culturally linked to ancient Japanese).

For Suda Gunji rocks have mystical import and a sense of presence. His photographs back up his assertions. Once numinous rocks with awe-inspiring qualities were the only shrines people needed for their nature worship. Now however they have come to occupy a peripheral or subsidiary position away from the Sanctuary, hidden in the woods or housed in an Okunoin (back shrine).

For ‘Big Rock Hunters’ like myself, however, these sacred rocks are central to the religion, for they resonate with the energy of the universe. Mighty and magnificent, they stand in sobering contrast to the transience of human life. There is, after all, good reason why kami descend into them!

****************

For previous entries about rocks, please see Shigemori Mirei and the power of rocks, or this one on Alan Watts, or an extract from The Stones Cry Out, or the awesomeness of Okayama rocks, or even The Dao of Rock.