Japan’s central myth is that Amaterasu, the sun-goddess, retired to a Rock Cave after the upsetting antics of her brother, Susanoo. As a result the world was deprived of her radiant light. Some have interpreted this as a reference to a solar eclipse, but given the festivities put on to draw out the sun it seems more in line with other midwinter celebrations around the world aimed at reviving the dying earth and its waning energy.

Faced with midwinter darkness, the other gods held a festival to rouse the sun-goddess from her cave. The shamanic dance of Ame no Uzume, who exposed her breast and genitals as a sign of fecundity, instigated the process by which the sun was induced to return. In this way light and warmth returned once more. Make merry, runs the message, and the ritual jollity will help ensure a miraculous rebirth!

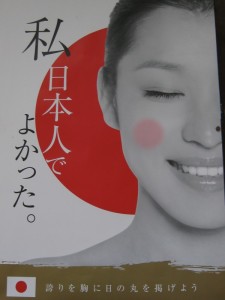

Opening the door of the Rock Cave behind which Amaterasu is concealed

Kyoto today is cold, grey and the sun is hid within a heavenly rock cave of thick clouds. But it’s a time to rejoice, for the shortest day of the year is upon us, and from here on we’ll be heading towards spring, new growth and revival. Let us set up bright lights, feast and drink to dispel the forces of darkness. All hail the eternal cycle of nature!!

Celebration of the midwinter solstice is a worldwide phenomenon, as noted in an article in the Huffington Post:

Opening of the rock cave

“In 2011, the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere will occur on Dec. 22, 2011…. Officially the first day of winter, the winter solstice occurs when the North Pole is tilted 23.5 degrees away from the sun. This is the longest night of the year, meaning that despite the cold winter, the days get progressively longer after the winter solstice until the summer solstice in 2012.

The winter solstice is celebrated by many people around the world as the beginning of the return of the sun, and darkness turning into light. The Talmud recognizes the winter solstice as “Tekufat Tevet.” In China, the “Dongzhi” Festival is celebrated on the Winter Solstice by families getting together and eating special festive food.

Until the 16th century, the winter months were a time of famine in northern Europe. Most cattle were slaughtered so that they wouldn’t have to be fed during the winter, making the solstice a time when fresh meat was plentiful. Most celebrations of the winter solstice in Europe involved merriment and feasting. In pre-Christian Scandinavia, the Feast of Juul, or Yule, lasted for 12 days celebrating the rebirth of the sun god and giving rise to the custom of burning a Yule log.

In ancient Rome, the winter solstice was celebrated at the Feast of Saturnalia, to honor Saturn, the god of agricultural bounty. Lasting about a week, Saturnalia was characterized by feasting, debauchery and gift-giving. With Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, many of these customs were later absorbed into Christmas celebrations.

One of the most famous celebrations of the winter solstice in the world today takes place in the ancient ruins of Stonehenge, England. Thousands of druids and pagans gather there to chant, dance and sing while waiting to see the spectacular sunrise.” (Article by Jahnabi Barooah)

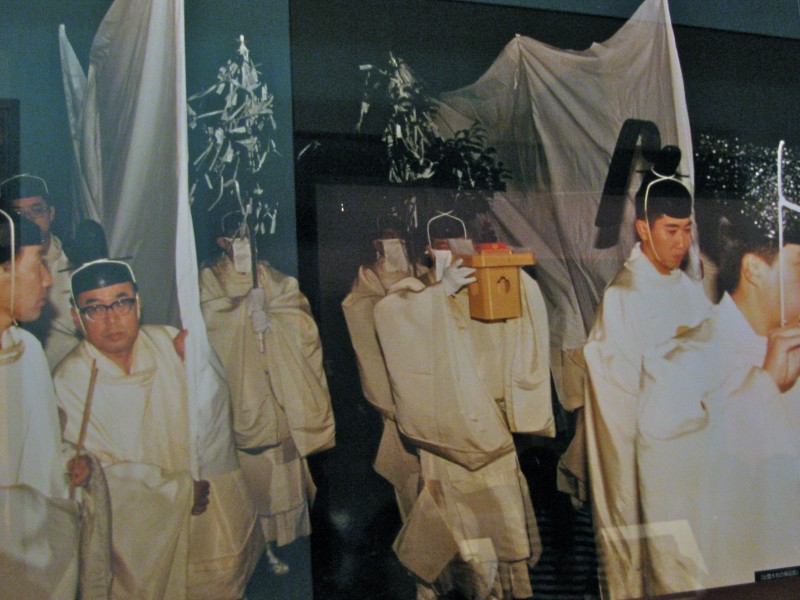

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?

Sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice. Zen or Shinto values?