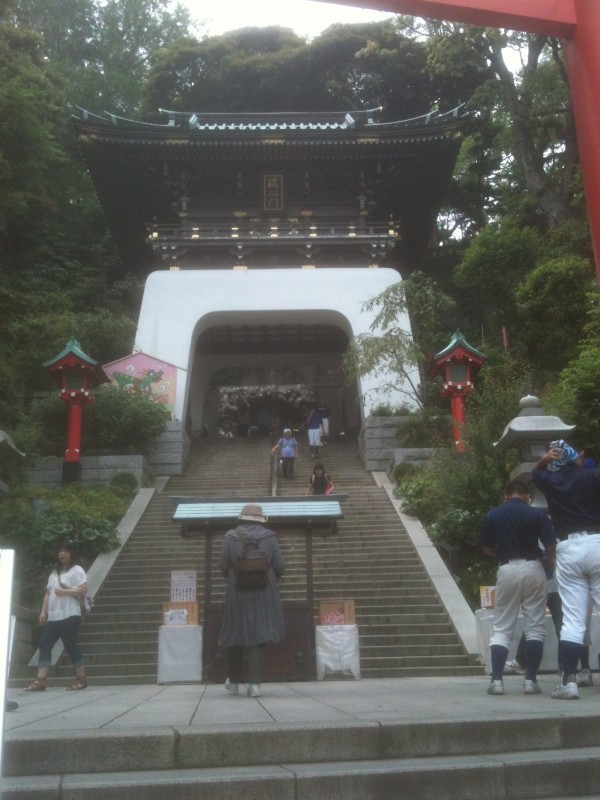

The entrance to Nobeno Shrine in Hisai, Mie Prefecture, where Florian Wiltschko is working as a priest

Green Shinto is delighted to carry an interview with Florian Wiltschko, a foreigner who has become the first non-Japanese in history to obtain an official priest’s licence through the Jinja Honcho system. There have already been postings about Florian on this site (see here for instance), so it was a pleasure to meet the young Austrian in person recently at his shrine in Mie Prefecture and to hear from him directly.

****************

1) How did you come to be interested in Shinto?

I was interested in traditional Japan since my early teenage years. I visited for the first time when I was 14. Then I started to read about things like Budo, Sado, Shodo etc. and found that all these traditional ways have one and the same origin: Shinto. And I was fascinated by the way that Japan takes foreign cultures and adapts them. In 2007 I was introduced to the Ueno-Tenmangu shrine in Nagoya, where I was able to train in Shinto. [The Ueno-Tenmangu Shrine has compiled a useful listing of English articles about Shinto here.]

2) What made you decide to be a priest?

After becoming interested in Shinto, I began to practice by worshipping the KAMI at home. While I was taking the first steps along this long road, I became interested more and more and finally decided to make it my lifestyle. I was attracted by the openness of Shinto, which is not the kind of religion with a membership. The torii for example are open to all, so no one is excluded. In Austria and Europe, people’s identity depended on what church or religion they belonged to. But Shinto does not create that kind of division. In fact it’s not a religion in a Western sense at all. I like the aesthetics of Shinto too, such as the design of shrines. Everything has a purpose and it belongs to a profoundly beautiful view of the world. But becoming a priest was not an easy path, and it took a lot of hard work and endurance.

3) How exactly did you go about getting a licence?

3) How exactly did you go about getting a licence?

In Nagoya I was introduced to the Prefectural Shrine Headquarters, where they do training for one month to get the basic license [for those who have already served at a shrine]. Later, it was suggested that I apply for a higher license, so I decided to take the one year course at Kokugakuin University in Tokyo. I was worried of course about how I would be treated because there were no other foreigners. But I was encouraged by those around me, especially by the advice that not allowing foreigners to enter the priesthood would be ‘un-Japanese’! I see a fundamental part of Shinto as being open to all.

4) How did you get your first position at a shrine in Shibuya?

After graduating from Kokugakuin, I was given a chance to work at Konno Hachimangu, very near the University. One of my classmates who became headpriest there introduced me, and I was treated sympathetically and was able to understand Shinto in a deeper way. I didn’t feel people treated me as a foreigner, but they accepted me as a priest.

5) Why and when did you move to your present position?

I moved to Nobeno Jinja in Hisai (Mie prefecture) in May 2016, where my wife is the head priest’s daughter. Now I’m involved with working on the shrine and helping to improve it. My duties are mainly with shrine rituals as the head priest is concerned with the kindergarten we run. I also helped run the annual festival this year, and we could restore the traditional way of carrying the mikoshi on the shoulders after having used a van to carry it for many years. We also have a big anniversary coming up soon for which we have various plans.

The Honden, Heiden and Haiden at Nobeno Shrine are housed in three buildings joined to each other

The interior of the main building has recently been restored with some choice materials: hinoki (Japanese cypress) for the Honden, imported Thai ironwood for the Heiden, and marble for the floor of the Haiden.

*************

For more about Florian, see this 2014 article from the Japan Times. There is also an extensive interview with him on the nippon.com site here. For an article covering the whole range of foreign priests in Shinto, please see this Japan Times article.

Readers living in Tokyo may well be interested in this talk by a leading figure in the world of Shinto Studies….

Readers living in Tokyo may well be interested in this talk by a leading figure in the world of Shinto Studies…. One of the striking aspects of Shinto is the vagueness and multiplicity that characterize descriptions of the gods (kami). The general understanding today is that kami are spiritual (immaterial) entities that attach themselves to particular things (rocks, trees, mountains, etc.); however, there are also beliefs that natural objects are divine in themselves. In addition, human beings can, in certain cases, be deified as well. The notion of kami also shares some semantic elements with concepts such as mono (entity endowed with supernatural powers), tama (spirit), and kokoro (mind). In this paper, I present some aspects of premodern Japanese discussions on the body of the kami (shintai), with their multiplicity and ultimate irreducibility, with special emphasis on medieval doctrinal texts and early modern philosophical treatments by Confucians and Nativists. I will suggest that a shared feature of the theology of the kami throughout history is a constant oscillation (and indecision) between materiality and spirituality, a structural oscillation that is responsible for both the constancy of certain themes and religious innovation.

One of the striking aspects of Shinto is the vagueness and multiplicity that characterize descriptions of the gods (kami). The general understanding today is that kami are spiritual (immaterial) entities that attach themselves to particular things (rocks, trees, mountains, etc.); however, there are also beliefs that natural objects are divine in themselves. In addition, human beings can, in certain cases, be deified as well. The notion of kami also shares some semantic elements with concepts such as mono (entity endowed with supernatural powers), tama (spirit), and kokoro (mind). In this paper, I present some aspects of premodern Japanese discussions on the body of the kami (shintai), with their multiplicity and ultimate irreducibility, with special emphasis on medieval doctrinal texts and early modern philosophical treatments by Confucians and Nativists. I will suggest that a shared feature of the theology of the kami throughout history is a constant oscillation (and indecision) between materiality and spirituality, a structural oscillation that is responsible for both the constancy of certain themes and religious innovation.

This is part of a series on Lafcadio Hearn, a Shinto sympathiser 100 years ahead of his time. Though he was not as proficient in language terms as his great Shinto contemporaries, such as B.H. Chamberlain and W.G. Aston, he had a mastery of words which was striking enough to win worldwide attention.

This is part of a series on Lafcadio Hearn, a Shinto sympathiser 100 years ahead of his time. Though he was not as proficient in language terms as his great Shinto contemporaries, such as B.H. Chamberlain and W.G. Aston, he had a mastery of words which was striking enough to win worldwide attention.