Star of last year’s festival – the Ofune float representing the ship in which legendary Empress Jingu sailed for Korea. Rebuilt after 150 years, following its destruction in the Great Fire of 1864, it is the last in the July 24 parade of floats. On its side it carries sixteenth-century fabrics from Portugal.

The Hachiman float bears a torii, pine tree and shrine dedicated to the kami

It’s been a busy week for Kyoto.

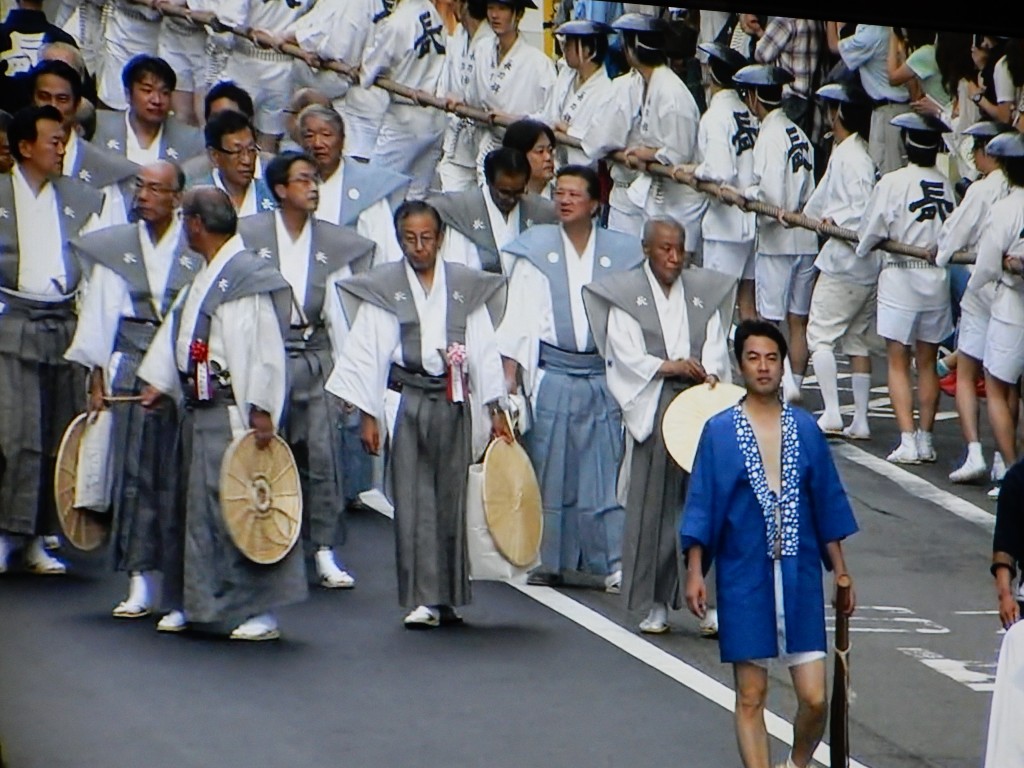

The second parade of the Gion Matsuri, which takes place on July 24, celebrates the return of the Yasaka Shrine kami from their week-long ‘holiday’ in the city centre where they reside in a resting place known as otabisho. The parade of floats takes place in the morning to entertain the kami, who are moved in an afternoon procession of mikoshi known as Kanko-sai.

In the evenings before the parade people are able to walk around the floats and view the treasures on display as well as pray at the shrines. Religious goods are on sale, and there is a general atmosphere of festivity. As this is the second time for this to happen within a week, crowds are far fewer than for the Saki Matsuri (Preceding Festival).

The occasion offers the perfect opportunity to view the floats in greater detail and to talk with some of the participants. It brings one close to the neighbourly nature of the festival. And according to old-timers, it’s much more like the Gion Festival of old when one could wander around at leisure rather than be crushed by the tourist throngs in the sweltering heat.

The three mikoshi from Yasaka Jinja that stand at the spiritual heart of the Gion Matsuri, resting in the centre of town at the ‘otabisho’ where they are on display

Musicians play at the otabisho of the mikoshi in Shijo Street, downtown Kyoto

The quiet conditions of the Ato Matsuri allow leisurely access to the float buildings where the religious purpose of the festival is apparent.

The diversity of float subjects can be seen at the Kurunushi yama, which honours a Heian-era poet, Otomo Kurunushi. One of the Six Saints of Poetry in the Heian Era, he is represented by a sacred figure which dates back to 1789.

The Kurunushi float has cherry blossom, of which the poet was fond. Since Kuronushi means black lacquer, the float is different from others in not being bare wood but black-lacquered.

A political festival fan – and for once it’s not nationalist but a message to Protect the Peace Constitution that Japan has had since WW2 (‘Protect Article 9 – Don’t turn Japan into a war-capable nation’)