Shinto garden by Shigemori Mirei at Matsuo Taisha

In my investigations into Zen this morning, I had something of an epiphany – or perhaps I should say, an awakening. Both Zen and Shinto share roots in Daoism (Taoism). Zen it has been said is the result of Indian Buddhism colliding with Chinese thought. And Shinto was conceived linguistically as shendao – the Way of the Gods. In other words, the thinking behind the Way of the Tao is fundamental to both. As Alan Watts explained in his very last book (1975), Tao is the Watercourse Way, flowing through the universe like an animating force.

Rock worship at Kamigamo Jinja

So, you may ask, if Zen and Shinto both share this in common, why are they so very different in form and belief? Why is one kami-oriented and particularist, while the other is self-oriented and universal? Why does Shinto look to this life, while Zen dwells on another?

Well, the thought struck me that they may not be as different as they seem. Both are after all based on intuitive understanding and repudiate logic and words. Zen prides itself on a transmission outside the scriptures. Shinto has no scriptures. Both in short treasure non-verbal understanding. ‘He who knows does not speak; he who speaks does not know,’ said Lao-Tzu.

In the Tao Te Ching, it is said the Way can never be known or defined. It can, however, be sensed or experienced, and its principles are observable in Nature. In Zen this is internalised as people seek their true inner nature. In Shinto there is the concept of kannagara, which in effect means following the laws of nature. Both seek the Way, but whereas Zen looks inside, Shinto looks outside. The former goes to the mountains to get closer to self, the latter goes to the mountains for closeness to the kami. And here perhaps is the vital difference between them, for whereas the former is deeply personal, the latter is community oriented. Zen tells you to sit in silence. Shinto encourages communal celebration.

Living rocks at Togakushi Jinja

It may be no coincidence then that both religions treasure rocks. (Landscape architect Shigemori Mirei has done rock gardens for both.) Zen temples are full of rocks in their beloved dry landscape gardens. Shinto shrines are full of sacred rocks, bedecked with shimenawa straw rope or shide paper strips. Rocks in Zen may trigger enlightenment. Rocks in Shinto are sacred vessels into which kami descend. Both religions see them as something more than mere stone – they’re representational, mini-mountains, spirit-bodies. On another level, they’re symbols of silence, of the non-verbal, of the eternal.

Here again Daoism lies at the root. Daoist practitioners went into caves to meditate, and what are caves but hollowed out rock? Significantly, in the Zen garden rocks stand for Mt Horai, the Blessed Isles of the Immortals where Daoist sages live. They may also symbolise moments of time in a vast ocean of raked gravel. And beyond that they symbolise the biggest rock of all, the one on which we’re spinning round the solar system. In this way they’re symbolic of Mother Earth, which, to quote Alan Watts, produced humans in the same way that trees produce apples. We are then the children of rock, because the earth-rock has ‘peopled’ us into existence. When Shinto followers worship rocks, they’re worshipping their ancestors in a very real sense.

It turns out then that in both Zen and Shinto rock is a means to salvation. Don McLean was on the right lines all those years ago. Rock truly will save your mortal soul!

Zen garden by Shigemori Mirei at Zuiho-in, Daitoku-ji with Mt Horai at the far end, from which a peninsula stretches out towards an individual rock, marooned and all at sea.

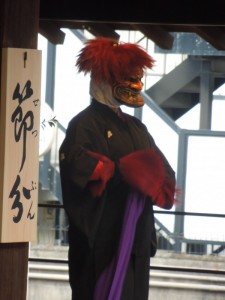

Yes, it’s that time of year again, and the shrines and temples will be open on Feb 3 (some on Feb 2) for bean throwing to dispel the demons that accumulate in the long dark nights of winter.

Yes, it’s that time of year again, and the shrines and temples will be open on Feb 3 (some on Feb 2) for bean throwing to dispel the demons that accumulate in the long dark nights of winter.