Sanzan means three mountains, in this case referring to Mt Haguro (414 m / 1360 ft), Mt Gassan (1984m / 6509 ft) and Mt Yudono (1504m / 4934ft ). The three sacred mountains in Yamagata Prefecture are said to represent the past, present and future, but practically speaking the small hill of Mt Haguro acts as entry point for Mt Gassan, where ascetic exercises are performed. The more remote Mt Yudono, only accessible by walkers, serves as holy sanctuary, and in the past worshippers were required not to speak of what they saw there.

According to tradition, Mt Haguro grants happiness, Mt Gassan consolation, and Mt Yudono rebirth. Since I was not looking for rebirth, nor did I feel in need of consolation, I decided the gentle slopes of Mt Haguro would suit me just fine. In fact I had visited once before and remembered fondly the magical sight of its five storied pagoda – a work of art in harmony with the surrounding cedars. Santoka, the wandering poet, wrote of Westerners conquering mountains whereas Easterners contemplate them, while he himself ’tasted’ them. I knew what he meant, for the fine taste of Haguro lingered on my lips.

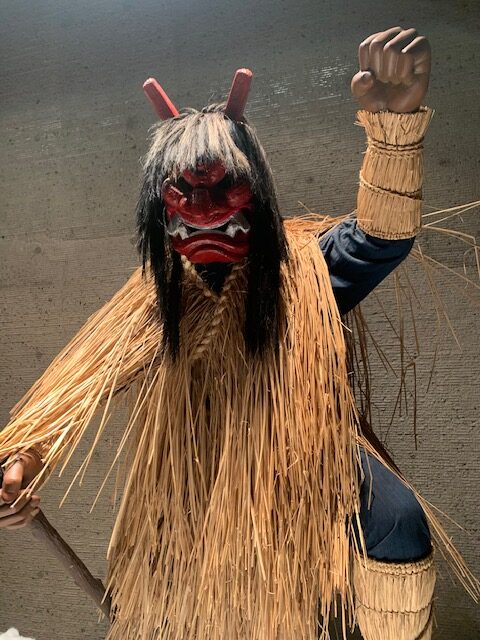

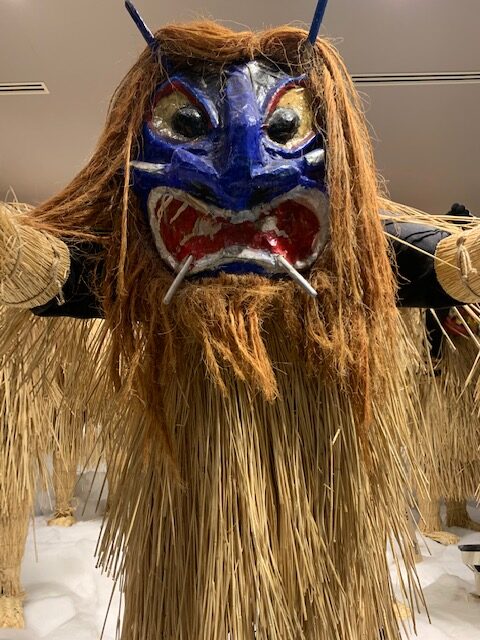

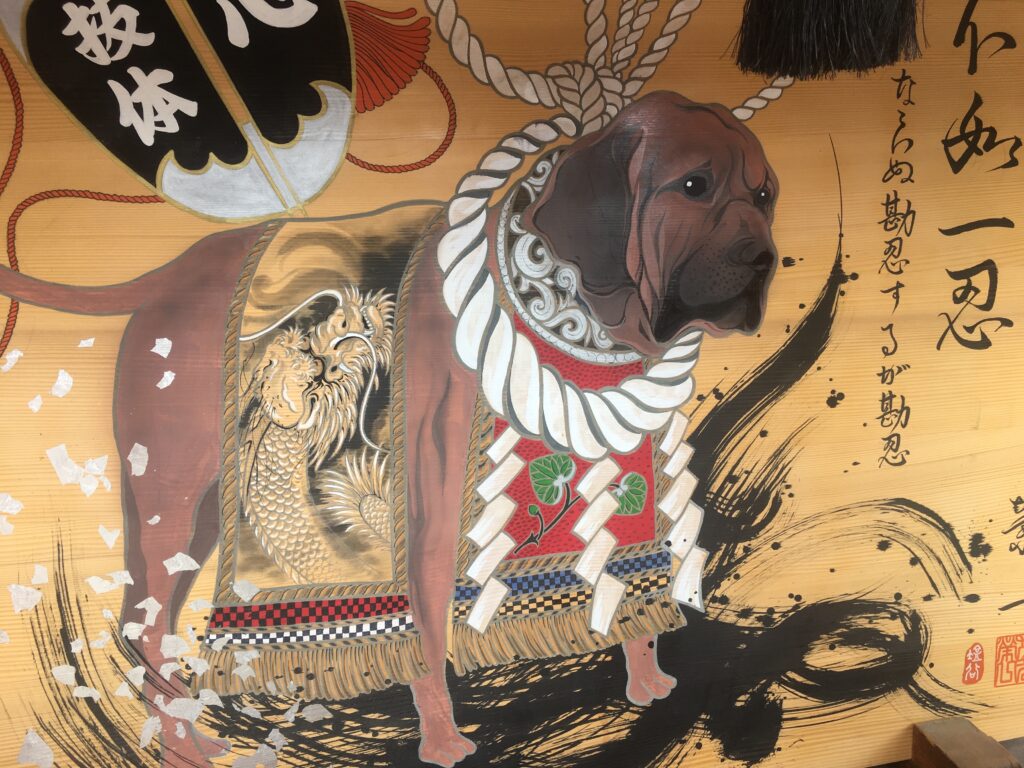

The bus from Tsuruoka emerges into a timeless landscape in which tiny figures in farmer’s clothing are dwarfed by misty mountains, as in a Chinese ink painting. When we reached the foothills, a large torii straddling the road announced we were entering the realm of the kami, and to either side were conspicuous signs of religiosity – shrines, buddhist statues, and shimenawa rice rope denoting sacred objects. Most striking of all was an enormous oversized haraegushi (purification stick) that looked like a relic from the Age of the Gods, when heroic figures and giant ogres strode the countryside.

At the entrance to the trail up Mt Haguro stood a run-down public toilet, placed strategically for the relief of visitors to the realm of the sacred. Despite its mosquito-ridden condition, someone had taken the trouble to place social distance markers on the floor. It was impressive. Even here, alongside the ancient traditions, modern hygiene prevailed.

Immediately on entering the woods the fresh fragrance of cedar became apparent and it was noticeably cooler, welcome relief indeed on such a warm day. Noticeboards announced with a concern for precision that the pathway had 2446 steps, and that lining the righthand side were 281 trees while lining the left were 301. This was thanks to the 50th head priest, who had laid out the approach over a period of thirteen years in the seventeenth century.

The pathway into the woods begins with a gentle descent, accompanied by the refreshing sound of water running down either side. Since my last visit there had been a significant change in that signs were bilingual for the benefit of tourists, and in front of a small wooden shrine was an announcement in English; ’Presiding kami Amenotajikarao no mikoto, Divine virtue: Proficiency in arts and sports.’ It seemed an invitation to pray, and praying in Japan means paying, so I tossed a coin into the offertory box and prayed for proficiency in arts. The sports I was willing to forego.

Further along the trail, the outline of a pagoda became apparent. From a distance it was barely discernible amongst the trees, for though it is an impressive twenty-nine meters high (95ft), it nestles beneath the canopy of the surrounding cedars. The result is a harmonious blending of art and nature. The impossibly tall trees have slender trunks stretching skywards as if reaching for heaven, while the pagoda exhibits elegance combined with stunning craftsmanship. If you stand below it and try to work out how the joints fit together, your brain is sure to get scrambled. And all that interconnecting complexity is done without the use of nails.

At this point, covered in a film of sweat, I decided I had had enough. Foolishly I had not brought any water, and my back was aching. I had intended to press on to the thatched buildings of Dewa Shrine, but I knew the kami would forgive me if I turned back. On the bus to Tsuruoka, I watched the mountains recede into the distance and thought of Basho. Trained in Zen, he was open to all forms of spirituality as is the Japanese way, and he had managed the full course at Dewa Sanzan, austerities and all. But then, I consoled myself, he was a mere forty-five at the time. When he visited, It had also been a warm day and he wrote of relief from the summer heat.

The coolness

And a faint three-day moon –

Mount Haguro

After a week at Minamidani (South Valley), Basho climbed the more demanding Mt Gassan and did ascetic exercises, before proceeding to Mt Yudono. Given the taboo on revealing what happens there, he cleverly wrote of it by not writing of it. (The Tsuruoka tourist board are less compliant, for their brochure explicitly describes the sacred object of worship.)

Yudono

of which I may not tell –

sleeves wet with tears

The mountain experience stimulated the poet’s imagination, and brought out his playful side too. The ‘De-’ of Dewa Sanzan means exiting, or emerging, and Basho used this in a haiku that sees him emerge from the mountains not to some great spiritual insight, but to vegetables. The ‘first of the season’ eggplants were prepared specially for him by his pupil, Nagayama Juko.

How unusual –

emerging from Dewa

to first eggplants

*********************

For another Green Shinto piece on Dewa Sanzan, please click here.