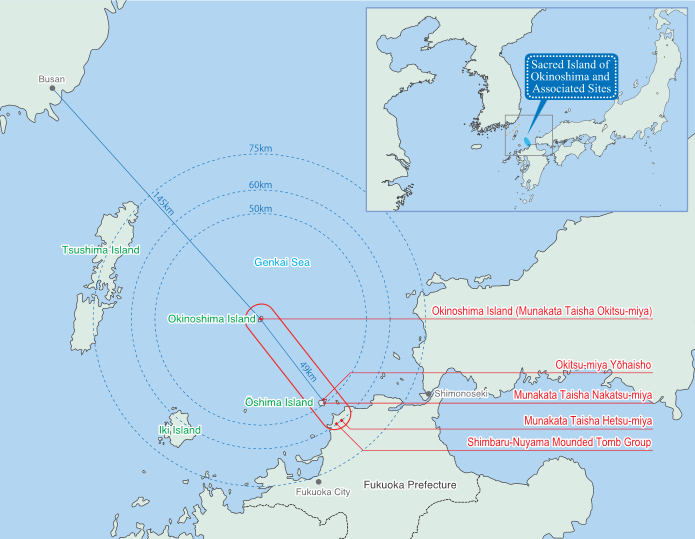

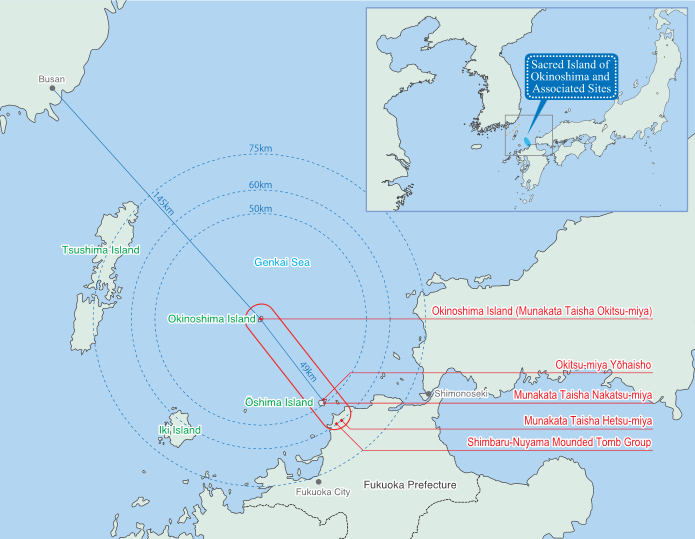

An exciting World Heritage application is in process, and members of ICOMOS, the Unesco vetting committee, have already taken the first steps of visiting the site. The nomination will be made in January 2016 with a view to securing registration as a World Heritage in 2017. The property covers the Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region of north Kyushu. The information and illustrations below are taken from http://www.asahi.com/ad/okinoshima2015/

Okinoshima (Okitsu-miya, Munakata Taisha)

Okinoshima has long attracted the devotion of the local people of the Munakata Region in Fukuoka who have fished the waters near the island from ancient times. Their nature worship of Okinoshima developed into a faith that has been passed down through generations to the present day. The entire area of Okinoshima is still a sacred area, and, due to ancient taboos including strictly enforced entry restrictions, the ritual sites and natural environment of the island have been preserved almost intact.

This property is an exceptional example of the cultural tradition of worshipping a sacred island, which has evolved and has been passed down from ancient times to the present.

The property consists of Okinoshima (Okitsu-miya), Okitsu-miya Yohaisho, Nakatsu-miya, and Hetsu-miya, which constitute the compounds of Munakata Taisha; and the Shimbaru-Nuyama Mounded Tomb Group.

Ancient Rituals on Okinoshima

Along the maritime route to Korea, the people of the Munakata clan, a prominent family in ancient Japan, played an important role in overseas exchange due to their excellent navigation skills. The Munakata clan dominated what is now called the Munakata Region and conducted rituals based on the worship of Okinoshima. As exchanges between Japan and the Chinese and Korean dynasties became active in the late fourth century, rituals were conducted on Okinoshima to pray for safe ocean crossings and successful overseas missions. The large-scale rituals that were performed on Okinoshima are described in this document as “state rituals,” sponsored by the ancient Japanese state, to distinguish them from smaller local rituals. These “state rituals” would have been impossible without the local population’s participation, particularly the Munakata clan. Only through its ties with this clan could the ancient Japanese state conduct these rituals and engage in exchanges with its Chinese and Korean counterparts.

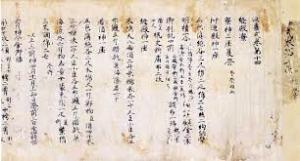

The ancient ritual sites on Okinoshima are preserved today almost intact due to the island’s remote location and local taboos limiting access to it. Archaeological excavations on Okinoshima have yielded some 80,000 precious ritual artifacts, all of which are collectively designated as a National Treasure of Japan. Ritual styles on the island changed over a period of some 500 years, from the late fourth century to the end of the ninth century, in four stages: they were first performed atop huge rocks on the island, then in the shadows of these rocks, then partly out in the open, and finally entirely out in the open. Ritual offerings discovered on Okinoshima include some of the same objects that were used in the formal ritual framework systematized by the Ritsuryo state in later years. The Okinoshima ritual sites are the only archaeological sites in Japan that bear witness to the process by which ancient nature rituals were formalized and developed into a form that still survives today.

Okinoshima Ritual Sites

The Shimbaru-Nuyama Mounded Tomb Group is a group of Munakata clan tombs. Members of the clan had excellent navigational skills and engaged in overseas exchanges. The clan built 41 mounded tombs of various sizes on a plateau overlooking a sea inlet, during a period that almost exactly coincides with the period when ritual practices were flourishing on Okinoshima.

The view from atop this plateau extends seaward to the island of Oshima and beyond it to Okinoshima and the Korean peninsula. The Shimbaru-Nuyama Mounded Tomb Group is intrinsically connected with Okinoshima, a landmark on sea voyages along that route, and bears witness to the local population that worshipped the island.

Shimbaru-Nuyama Mounded Tomb Group

Evolution of the cultural tradition of worshipping a sacred island

From the latter half of the seventh century onward, rituals similar to those performed at Okinoshima open-air ritual sites were also conducted at the highest point on the island of Oshima, and on a plateau facing a sea inlet on the main island of Kyushu. These ritual sites are known as Mitakesan and Shimotakamiya.

Nakatsu-miya, Munakata Taisha

All three sites are mentioned in Japan’s oldest historical records, which were compiled in the early eighth century, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan). They are mentioned by the names of Okitsu-miya (literally, “offshore shrine”), Nakatsu-miya (“midway shrine”), and Hetsu-miya (“seaside shrine”), where the Three Goddesses of Munakata (Tagorihime, Tagitsuhime, and Ichikishimahime), originally worshipped on Okinoshima, respectively resided. This is an extremely rare example of a case where the three existing ritual archaeological sites match and support their descriptions recorded in ancient times.

Munakata Shrine, now called Munakata Taisha (Munakata Grand Shrine), consists of the three shrines of Okitsu-miya on Okinoshima, Nakatsu-miya on Oshima, and Hetsu-miya on the main island of Kyushu, which together form a single vast maritime precinct where the Three Goddesses of Munakata continue to be enshrined and worshipped today.

Okitsu-miya Yohaisho, for distant worship of the Okinoshima sacred island

Okitsu-miya Yohaisho was built on the northern part of Oshima for the purpose of worshipping Okinoshima from afar, since taboos strictly prohibited landing on the sacred island. The existence of this shrine shows the continuity of Okinoshima worship.