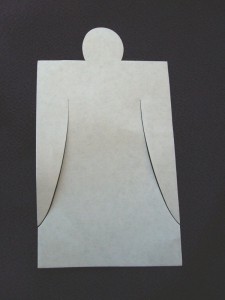

Buddhist style memorial with posthumous names

Transfer of the spirit of the deceased to the memorial tablet

This crucial and special rite, performed by a Shinto priest, usually takes place during the wake. The spirit of the deceased is called out of the body and installed in the memorial tablet. The senrei sai is found only in Shinto funerals. However, Edo-period Shinto funerals do not include the senrei sai, so it is probably of twentieth-century origin.

The Shinto memorial tablet is similar to a Buddhist memorial tablet in form and function, and for that very reason it is called by a different name: reiji, not ihai. The reiji, less ornate than the Buddhist ihai, is usually made of plain wood with the posthumous name painted in black. A mirror, shaku (the wooden pallet that symbolizes priestly authority), or something closely connected with the deceased may also be used as the reiji.

Shinto priests holding the ‘shaku’, symbol of authority. This can be used as the ‘reiji’ into which the spirit of the dead is transferred.

In summary, the rite proceeds as follows:

1 . Priests and mourners enter the ritual site, usually a room in the house.

2. The chief priest bows once, and the mourners then bow.

3. The central rite is performed in darkness (see below for a discussion of the nighttime setting of Shinto funerals). The lights are extinguished, and the priest stands in front of the coffin. The reiji has been placed before the coffin. The priest removes the cloth covering from the reiji and faces the reiji toward the coffin. He may go right up to the coffin, open a small window in the coffin that allows one to see the face of the deceased and hold the reiji near the face (so that the deceased can “see” the reiji? or because the vital spirit comes out with the breath?). The priest may wear a gauze mask over his mouth and nose, so that his own mortal breath (or, worse, spit) cannot defile the memorial tablet or the spirit of the deceased. At the same time, the mask protects the priest from the impurity of the corpse.

This ambiguity — deceased as divine, corpse as polluted — is evident at several points in the Shinto funeral. The priest recites the appropriate prayer, which effectively moves the spirit from the corpse to the reiji — from its fleshly housing to its new abode in the spirit tablet. The priest puts the cover back on the reiji. After the spirit has been installed, the tablet is placed in the temporary ancestral altar. The mourners maintain silence during this rite. Now the lights can be turned back on.

4. The priests and others sit in front of the temporary ancestral altar.

5. Offerings are presented. During this time, musicians may play particular gagaku music used only during wakes and funerals.

7. The priest offers another prayer. This prayer is intended to pacify the spirit of the deceased.

8. Offering of tamagushi [see previous entry for Shinto Death 6].

9. The offerings are removed (or they may be left out).

10. The chief priest bows once. The priests leave the site.

It is through this rite that the spirit of the deceased is transformed into a divine spirit. Thus, it is at this point that the posthumous name begins to be used. The spirit of the newly dead person is volatile, liminal and polluted. It is more dead (so to speak) at this first stage of its spirit life and therefore more polluted, due to its closer association with the impure corpse. One Shinto spokesman states that because the spirit of the deceased is polluted, it is placed in a temporary ancestral altar for fifty days after the death.

A Japanese funeral with photo of the deceased and name tablet (courtesy moviespix.com).

After the spirit has entered the reiji, the reiji should be moved to a separate room until the coffin leaves the house (probably to prevent the spirit from reentering the body, although there is no official Shinto support for this interpretation). The spirit is now considered to be separate from the body, but the body continues to receive attention.

Several Shinto priests described to me a dualistic understanding of the spirit/body relationship (the body is temporary clothing to be outgrown and thrown away; the spirit continues to live for a very long time, maybe forever [none had firm views on eternity]). Nonetheless, it seems to me that in practice Shinto, like most of Japanese religion, views a person as a conjoining of two or more essences that separate at death. One inhabits the memorial tablet; another stays with the bones in the grave. It is important to communicate with and make offerings to both.

It would be hard to argue that the grave can be forgotten (“it’s just bones in there”) and only the memorial tablet remembered. Or vice versa. This double-spirit is reminiscent of the Chinese “souls,” but there is no explicit use of the terms in today’s Shinto.

In twentieth-century Japan, the dead also seem to inhabit their memorial photograph. In funeral processions, three items are carried with equal solemnity: the memorial tablet, the cremated remains, and the photograph. After the funeral, the photograph is usually set in or near the altar and will remain there for decades. Some people tell me that the expression on the photograph changes in accordance with the mood of the deceased.

A look at the popular Japanese books on “spirit photographs” will convince anyone that Japanese spirits have an affinity for snapshots. The Japanese college students whom I teach make presentations using slides they have taken of religious places or objects (temples, shrines, statues, amulets, votive tablets, seldom graves). The students often do not want to keep the slides after they have finished their presentation because they are “afraid” of the “ghosts” or “spirits” in the slides. Throwing the slides out is not a good solution, since it would make the spirits angry. What to do? Give the slides to the teacher.

Finally, the deceased may appear in dreams. It is hard to say whether this is a fourth spirit or one of the other two or three that has left its usual station in order to contact a sleeping relative.

Sometimes two reiji are used and the spirit of the dead is installed in both of them. One of the reiji will be burned with the corpse when it is cremated, and the other one will be installed in the household ancestral altar.

One Shinto priest explained that a person’s spirit is “infinite, limitless, and divisible.” He made an analogy to the divisibility of a kami. During a festival with a portable shrine, part of the kami is in the mikoshi traveling around the shrine neighborhood, while another part of the kami remains in the main building of the shrine.

There’s been a notable upturn in Halloween decorations this year in Japan, and I have the impression the festival is about to be celebrated with more gusto here than in the West. Green Shinto has written before of

There’s been a notable upturn in Halloween decorations this year in Japan, and I have the impression the festival is about to be celebrated with more gusto here than in the West. Green Shinto has written before of