The extracts below from Elizabeth Kenney’s article will bring to mind the 2008 Oscar-winning film called Okuribito (The Departed), which begins with the mesmerising scene detailing the extraordinary care and deference with which the corpse is ritually cleansed. There is however an important step before that known as matsugo no mizu (the last water). Please read on…

*********************

1 . Wetting the lips of the deceased

A close relative of the deceased takes a disposable chopstick with cotton tied to the end, dips it in a small bowl of water and touches it to the lips of the deceased. Traditionally, a writing brush was used. Because today 80% of deaths occur in hospitals, a doctor and nurse may solemnly observe the rite, giving medical professionals a role in the rituals of death.

Symbolically, this last offering of water is the final chance to revive the corpse. Since the dead will no longer drink of the water of the living, this water is both an offering to the deceased and a guarantee that he is truly dead. In addition to providing hope (of revival) and proof (of death), this water is the first in a long series of offerings of food and drink made to the deceased in his new status as an ancestor.

Lying in his hospital bed, the deceased still has an ambiguous status: human yet dead. His last sip of water as a human is also the first he receives as an ancestor. The dead in Japan revert to a condition of babyhood, needing to be fed by living adults. This role reversal (children feeding parents) casts the living as maternal nurturers of the dead. The living provide the dead with the food they need in their new existence… it is thoroughly integrated into Japanese funeral practices, being performed by Shintoists as often as Buddhists, and usually without the presence of any religious official.

2. Washing the corpse

Both the Buddhist and Shinto dead (like the dead in most cultures) receive a last bath. Even today in Japan, it is usually relatives, rather than funeral or medical specialists, who perform this final cleansing. Today, people use alcohol and gauze (which may have been provided by the hospital or by the funeral company), rather than giving the deceased a true bath.

It may be, as several Japanese scholars contend, that the awareness of death pollution is diminishing in modern Japan. Death taboos are less strictly observed, and many young or middle-aged people do not readily think in terms of impurity or pollution (kegare). When asked, for example, why they do not send new year’s cards when there has been a death in their family or why they refrain from entering a shrine after a relative’s death, they will respond that it has to do with “sadness” or “mourning,” and the term “death pollution” is unlikely to be uttered.

Although the notion of death pollution (an intangible condition) may be fading, today’s Japanese (like citizens of other industrialized countries) are squeamish about the actual corpse. As death becomes less familiar to the Japanese, the bathing of the corpse may gradually become abhorrent.

Ritual purification of the body is important in life as in death

Several Japanese college students have told me they were “surprised” to encounter this rite after the death of their grandparent or great-grandparent. But the more important point is that these Japanese students did help wash the corpse or observed the activity (with some reporting that they felt “uncomfortable”). In contrast, American and Australian college students ask, “Isn’t it illegal?”

In Japan, the washing is already sanitized by the hospital setting, the use of alcohol, and the quickness of the procedure. The ritual washing may eventually be entirely in the hands of professionals, as it already is in the U.S.

While the intimate handling of the corpse grants the mourners a last chance to attend to the deceased, it is also the most polluting moment in the funeral process, since it requires direct contact with the corpse. Shinto priests naturally do not participate in the handling of the corpse (and neither do Buddhist priests). If the family needs guidance and support during this act, they will get it from a funeral company employee or from a community group. The Shinto priest does not arrive until the next stage.

The corpse needs not only to be bathed but dressed and made up (“death makeup,”). Buddhist rites focus on the dress of the deceased far more than do Shinto rites. A student told me that when her family bathed the corpse of her great-grandmother, they wore straw wreaths (“like a life-saver”) over one shoulder and across the torso. Her mother explained that the wreath “had the power to keep my great-grandmother from bringing us into the other world with her.”

The wreath is clearly akin to the big straw circles, like freestanding doorways, erected at Shinto shrines at the end of June and December. People step through these straw circles at the liminal times of midyear and year-end in order to purify themselves and ensure health and safety for the next half year.

Vaginal symbolism is surely also part of the meaning (rebirth), especially in the case of the family members attending to the deceased. By wearing the wreath, pushing themselves through the circular opening headfirst, they enact the dead person’s rebirth in the realm of the dead (but do not go all the way through themselves). At the same time, the straw wreath retains its symbolism as an agent of purity and thus protects the mourners from the power and pollution of death.

Stepping through the straw circle is a form of rebirth, whether in terms of a new purified self or of entering the world beyond

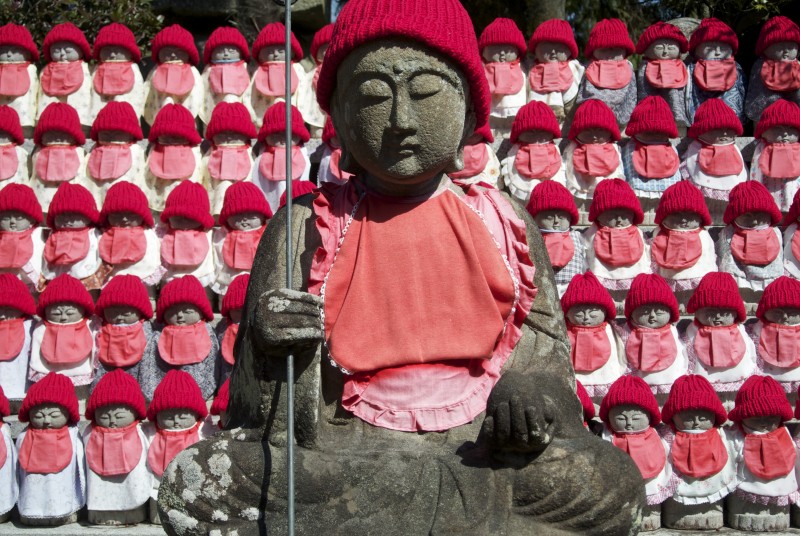

Jizo is the most widespread deity in Japan, to be seen across the country at crossroads, waysides, cemeteries and elsewhere. A guardian of the dead, he is portrayed in monk’s attire and seen as a guardian of the otherworld who ensures safe crossing, particularly for children. Though it’s customary to think of the deity as purely Buddhist, the passage below from

Jizo is the most widespread deity in Japan, to be seen across the country at crossroads, waysides, cemeteries and elsewhere. A guardian of the dead, he is portrayed in monk’s attire and seen as a guardian of the otherworld who ensures safe crossing, particularly for children. Though it’s customary to think of the deity as purely Buddhist, the passage below from

A reminder that tomorrow (Mon 28th) will be the harvest full moon, traditionally celebrated by the Japanese as the most beautiful of the year. There are lots of moon viewing parties, which in the past consisted of poetry making while sipping saké and admiring the reflection in a specially crafted cup. Japanese love of beauty at its best.

A reminder that tomorrow (Mon 28th) will be the harvest full moon, traditionally celebrated by the Japanese as the most beautiful of the year. There are lots of moon viewing parties, which in the past consisted of poetry making while sipping saké and admiring the reflection in a specially crafted cup. Japanese love of beauty at its best.