An Inari subshrine with ‘tama’ offerings that look relatively recent though the shrine is clearly untended

The first place I turned to in an attempt to get to the bottom of the Oiwa mystery was Fushimi Inari Shrine, since the Inari connection seemed so strong. However, one of the shrine staff assured us by telephone that there was absolutely no relationship with Oiwa Jinja.

The practice of putting up otsuka stone altars to Inari had started at Fushimi in Meiji times, he said, when people in trouble or ill health turned to ogamiyasan (mediums) who advised them on erecting otsuka with individualised names. No doubt the practice had spread to nearby Oiwa Jinja, he suggested. As for the present situation of the shrine, Fushimi Inari knew nothing and had no involvement.

So with the Fushimi connection proving fruitless, I determined to try the owner again. This time fortunately there was someone at home, and in response to my enquiry an elderly woman opened the door tentatively as we stood in the rain at the gate. For a few minutes it seemed she was going to dismiss us as she fended off our enquiries with polite but meaningless answers, but eventually she relented and invited us into the genkan (entrance area). For the next half an hour we were able to sit on the edge of the raised floor as she knelt before us and answered questions.

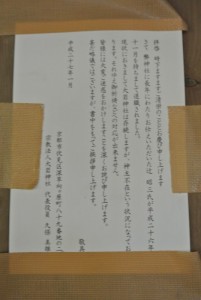

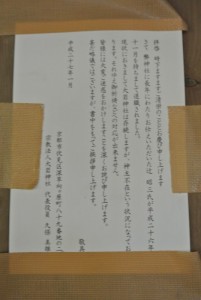

The small handwritten notice of abandonment

Information came in dribs and drabs, but a rather sad story emerged. She had married into the family, and her husband who had inherited the shrine had died unexpectedly at 50 without having told her much about it. The oldest son, who had been going to train as a priest, had also died. I got the impression that with the death of the son, the chance of saving the shrine had passed.

The youngest son, now married, lived with her but had his own career and no interest at all in the shrine. She herself seemed to have little interest in Shinto (at one point she could not remember the word for ‘the rope thing’ i.e. shimenawa), but had left everything up to the priest who had been in charge for the past forty years. Last year he reached the age of 85 or 86 and was no longer physically capable of running the shrine.

Because of the lack of income, the priest had only been part-time (I asked if the family had paid him; ‘a very small honorarium’, she replied). His main source of income had come from another job, and the priest’s son, an obvious candidate to take over the father’s job, had indeed become a priest but had taken the more financially secure route of working for Yasaka Jinja, where he was now one of the senior staff.

Before the war, Oiwa had apparently been a flourishing shrine with members from an Osaka fraternity visiting and donating. There had been too a tea room run by the priest’s wife for visitors. But things had changed after the war, with fewer visitors. Perhaps some of the believers had been killed, perhaps the new generation did not believe as their parents had, perhaps the Osaka fraternity had lost its charismatic leader.

The house of the Oiwa Jinja owner, substantial by Japanese standards

With an elderly priest and falling patronage, Oiwa Jinja had been on the decline for years. The person who kept the misogi place clean had become old and stopped his caretaker duties. Others who helped out had died off too with no one to replace them. Financially too, the shrine had become a burden. When her husband died, there had been hefty inheritance taxes to pay. And when torii or stones started to fall over and be a danger to the public, her family had to pay for the repairs. The priest’s retirement appeared to have brought matters to a head.

I wondered what would happen to the shrine now? She didn’t know, she said, she was thinking about what to do. Kyoto city was not interested in conserving it. She might ask Jinja Honcho (Association of Shrines). How about a business sponsor I wondered, but she dismissed the idea as impossible. Perhaps she could sell it someone, I suggested? No, she said. Impossible. It was a family heritage. It had to be kept out of respect to the family’s ancestors.

Stone altars stand in front of the abandoned shrine

She likened her position to the British aristocracy, saddled with debt and taxes but unwilling to give up the family estate. It seemed a good analogy. The aristocracy had to make compromises, living in a corner of their stately home and opening it to visitors. Perhaps she too would have to compromise in some way… but with no priest and a son who was uninterested, it was difficult to see an easy solution.

Perhaps there was land to sell off? Different parts of the mountain belonged to different people, she said. The bamboo forest for instance belonged to different people. Even the pond next to the lower portion of the shrine was not hers, and in fact there was a conservation group for it. Perhaps then that was a possible means of salvation – an Oiwa Jinja conservation group! It would of course take a good deal of initiative and good will to set up, requiring the energetic input of younger people. And there was little sign of that.

When it came to the history of the shrine, she said she knew nothing at all and advised asking the younger brother of her husband. He too said he knew nothing. So I was left to imagine what might have happened from the information I’d got so far. and my surmises were that after the Meiji Restoration a rich individual in the area of Oiwa Hill had decided to revive the local shrine. Perhaps he employed a priest called Tsuji, for the recently retired priest with that name was said to be the fourth generation.

The goreisho is an area of thanks which honours the spirits of all those who worked on behalf of the shrine

The newly restored Oiwa Shrine must have won the favour of ogamiyasan living in the area, and through the recovery of someone with TB the shrine won the reputation of curing people with lung diseases. Perhaps it was one such person who in prewar years had started the fraternity in Osaka, as a result of which the shrine had seen a profusion of otsuka and Inari subshrines.

Now they stand forlorn and abandoned, but the sacred rocks remain as a poignant reminder of the numinous power of nature. Japan’s decreasing population in an age of secular values mean that such scenes are going to be increasingly common. It means the ‘land of the kami’ will have to face a time of falling numbers too as the Age of the Gods fades further into the past.

The abandoned shrine will need a lot of money and energy if it is ever to be restored

7/7 (July 7) might be considered lucky indeed. And in Japan it’s closely associated with stars and lovers. How come?

7/7 (July 7) might be considered lucky indeed. And in Japan it’s closely associated with stars and lovers. How come?