Ray Tsuchiyama has written in with an article which appeared in an edition of Hana Hou!, the magazine of Hawaiian Airlines. Entitled The Last Jinja, it tells the story of the last standing shrine on the island of Maui. When I visited it some ten years ago, it looked forlorn and largely unused. I knew there was an elderly priestess in charge, but Ray’s article below explains the whole history that lies behind the building. It’s a fascinating story.

Ray Tsuchiyama has written in with an article which appeared in an edition of Hana Hou!, the magazine of Hawaiian Airlines. Entitled The Last Jinja, it tells the story of the last standing shrine on the island of Maui. When I visited it some ten years ago, it looked forlorn and largely unused. I knew there was an elderly priestess in charge, but Ray’s article below explains the whole history that lies behind the building. It’s a fascinating story.

***************************

Story By: Ray K. Tsuchiyama

In the uneasy summer after the Great Tohoku Earthquake three years ago, tormented by the fear of another quake and anxiety about nuclear contamination, my wife and I left our beloved Tokyo. We relocated to Kihei, Maui, a land of sunshine, windsurfers and retirees. Rather than reveling in a stress-free paradise, though, we felt uprooted—disoriented and discontented, immigrants in an alien land. We had lived in Tokyo for two decades; we missed its lights, its restaurants, our circle of friends. We tried to feel grateful to be surrounded by the natural beauty, but in truth our lives felt meaningless.

On a New Year’s Day five months after the move, we made our way to a weather-beaten old Shinto shrine—the last one left on Maui—perhaps searching for a link to the life we had left behind. The Maui Jinja Mission was different from the bustling, ornate shrines of central Tokyo: It was serene, almost too quiet. Until we met Torako Arine. The then-97-year-old wheeled herself toward us and in booming Japanese welcomed us to her “country shrine” and apologized for its dilapidated state. She called herself “the caretaker,” but the elderly Japanese entering the shrine addressed her as though she were a priestess—which, I soon found out, she was.

The jinja is a fixture on Maui, completed in 1917 to serve the island’s issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants). In the 1930s a nisei (second-generation) named Masao Arine left Maui to study Shintoism in Hiroshima. That’s where he met his future bride, coincidentally also from Hawai‘i: Torako was born in Waipahu. The couple arrived on Maui in 1941 to lead the shrine, but their timing couldn’t have been worse; six months later Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

The honden (Sanctuary) of Maui Jinja

During the war, Shinto was regarded with suspicion, and not without cause: The Japanese government had co-opted the peaceful religion to serve its imperialist agenda. As a result Shinto priests in Hawai‘i suffered terribly. Though he was an Upcountry Maui boy and an American citizen, Masao endured interrogation and incarceration, the sole occupant of a military prison in Ha‘iku. It was left to Torako to care for their six children. Meanwhile, nisei families continued to visit the shrine, especially at New Year’s—at least until the military police nailed the doors shut. They would remain so until Japan surrendered.

After the war, the jinja’s landlord terminated the lease to make way for Maui’s first mall, but Masao had saved up from his night job tending bar at the Wailuku Grand Hotel. The multitasking priest and his spouse bought land in Paukukalo, near Wailuku, and planned a major logistical project: They rented a crane to lift the jinja and had it towed two agonizing miles to its current site on Lipo Place. In November 1954, nisei families gathered at the new location surrounded by curious Native Hawaiian children. The couple had defied the odds and preserved both the shrine and the community.

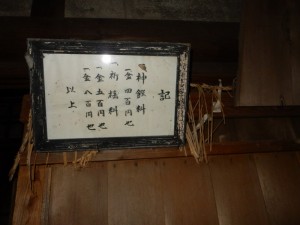

The Worship Hall has a large wooden ema placed above the entrance

When Masao died in 1972, there was no one to take care of the jinja. So at 58 Torako left for Japan to train in Shinto. After, she returned home to Maui and continued her late husband’s mission—a daunting one, as few ordained Shinto priests (barely 7 percent) are women. When I met her that New Year’s Day, I didn’t know anything about her history, about her determination, about how she had become the venerated, spiritual heart of a vanishing nisei community.

She asked whether we lived on Maui, and she must have sensed, I think, the hesitation in my reply. She smiled knowingly and moved on to perform rituals before a simple altar framed by flowers and faded paintings on the walls. She was so confident, so sure of every step, supremely placid and perfect in a building literally falling apart from salt winds blowing off the northern sea.

Last spring Torako Arine died at age 100. I think often of her smile that New Year’s Day. As I stood on that strange ground under a creaking roof, wrestling with my desire to be somewhere else, I watched an aged priestess in a crumbling shrine carry out ancient rituals with absolute presence. And I’ve never left.

Inside the shrine East meets West in a mix of chairs and traditional offerings

***************************

Ray reports that the community still holds services in the shrine, but that the building is tottering due to lack of funds. It is listed on a Historic Register for the State of Hawaii.

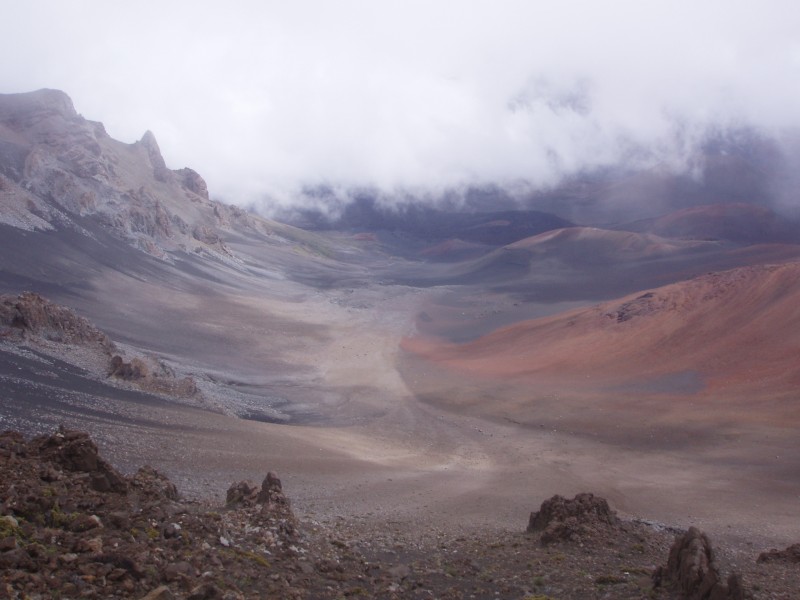

Maui has some awe-inspiring scenery…

… and plenty to be grateful for too.

It’s not often you get to play Indiana Jones, but that’s how it felt on a recent excursion to the overgrown Oiwa Jinja for there is something of the feel of Angkor Wat about the abandoned shrine. Oddly, after more than twenty years in the city I’d never come across this exotic gem before. Or even heard of it.

It’s not often you get to play Indiana Jones, but that’s how it felt on a recent excursion to the overgrown Oiwa Jinja for there is something of the feel of Angkor Wat about the abandoned shrine. Oddly, after more than twenty years in the city I’d never come across this exotic gem before. Or even heard of it.