Groups of young people, especially women, have become a common sight at shrines in recent years

In an interesting article on the net, religious scholar Shimada Hiromi examines the religious boom which has been evident among young Japanese in recent years. Personally I attribute much of this to the increase in nationalist sentiment, as a new generation reared on ‘patriotic education’ and pride in Japan turn to examining the roots of their culture rather than opening their minds to the outside world. With Abe’s right-wing government in control, there has been a palpable upturn in self-congratulation. TBS airs a programme called Rediscover Japan!, and ABC has Japan Astounds the World. Among the bestselling books is one by Tsuneyasu Takeda, Why is Japan the Most Popular in the World?

In the article below Shimada Hiromi seems to agree with this thesis, while adding an overview that looks at recent trends in Japan’s religious landscape. Along the way he examines power spots, the low cost of shrine visiting, the ‘new new religions’, the connection with roots and with nature, and he ends with a warning about the possible danger involved. He also makes what to my mind is a controversial statement about Shinto’s supposed uniqueness, based on its continuity and longevity. (For the original article, click here.)

*********************************************

Young Japanese men and women drawing inspiration from Japan’s ancient spiritual heritage.

by Shimada Hiromi (Originally published in Japanese on March 4, 2014.)

Queues at times of religious festivals can be impressively long, as here at New Year at Uji Jinja

As a religious studies scholar who writes a good deal on the subject of Japanese religion, I am a frequent visitor to Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples. These days I rarely go to any shrine or temple without running into a throng of young Japanese visitors.

This was not always the case. Not so long ago, touring temples was mainly a hobby of the elderly. But nowadays I encounter older people there much less often. One still runs into the occasional senior bus tour, but not that many. The most enthusiastic habitués of Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines nowadays are unquestionably young adults.

Record Turnout at Ise Grand Shrine

Among the most popular religious destinations last year was the venerable Ise Grans Shrine in Mie Prefecture. A record number of visitors made the pilgrimage in 2013, [eager to be present on the occasion of the shikinen sengu] and to see the buildings in their pristine new state. The Inner Shrine and Outer Shrine recorded a combined total of 14.3 million visits, well in excess of the 13 million predicted.

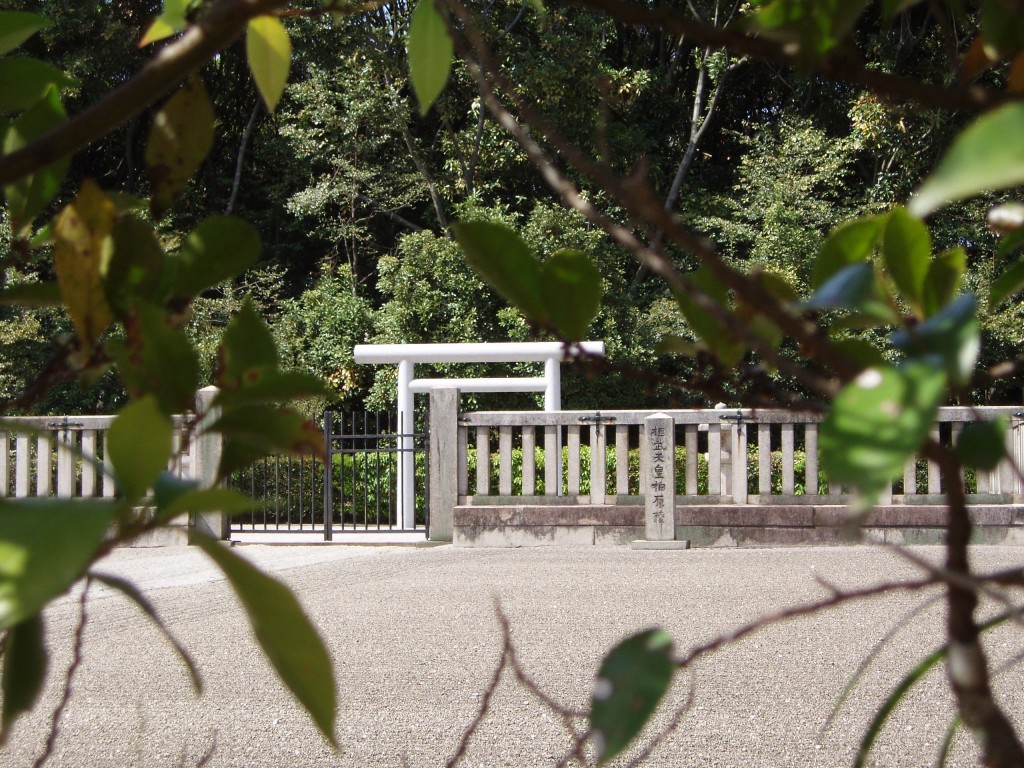

Particularly noteworthy, it seems, was the unprecedented number of youthful visitors to Ise. This was certainly the case when I made my own first post-sengū pilgrimage near the end of the year. Moreover, the young people I saw there had studied their Shintō rituals well — for example, bowing whenever they passed through the torii gate, whether entering or leaving. Their behavior suggested that they were there as something more than curiosity-seekers.

Kamigamo Jinja in Kyoto, which has recently undergone its twenty-year renewal

I had the same impression when I visited Kamigamo Shrine in Kyoto on a similar occasion three years ago. In preparation for its own shikinen sengū, scheduled to take place in 2015, the shrine was offering special tours in which visitors had the rare opportunity to view the Main Sanctuary close up. Before paying their respects at the shrine, they were also invited to hear a presentation by the head priest. I was surprised to find that the audience consisted almost entirely of young adults, who listened to the priest with the utmost attention.

I cannot tell you exactly when temples and shrines became such a popular destination for the under-25 crowd, but there is no escaping it. More importantly, it seems clear that these young visitors are not there just to see the sights. They have come to get in touch with the divine.

“Power Spots” and Budget Outings

Of course, the “power spot” craze surely has something to do with this phenomenon. In recent years Japanese magazines and websites have sought to capitalize on the popular new theory that certain sites have a spiritual energy that one can marshal for one’s own benefit. Mount Fuji has figured prominently in Internet rankings of power spots since it was designated a World Heritage site in 2013.

I cannot deny having overheard young visitors to temples and shrines whispering to one another they could “feel the power.” I have also heard people of that generation react to a Buddhist images in a museum or exhibition with comments like “This one has amazing power.” Still, I am convinced that this is more than just a passing fad.

The queue to pray at Tokyo Daijingu, a noted 'power spot'

Economic factors probably contribute to the trend as well. Despite all the talk about stimulating the economy, conquering deflation, and boosting wages, incomes remain stagnant, and steady jobs are hard to find. The younger generation is by no means insulated from the stresses and strains of this economy situation. The bottom line is that they have less money to spend on leisure activities, and visiting temples and shrines is a cheap and accessible form of recreation. Nowadays a day at Tokyo Disneyland costs at least ¥10,000 per person. But one can tour the grounds of Ise Shrine for nothing at all, apart from a few coins tossed in the offertory box. “Power spots” in general are a good choice for the budget-minded, and Shintō shrines, which typically charge no admission at all, are especially attractive from this viewpoint.

Still, while budgetary considerations doubtless play some role, they do not explain why the young visitors arrive at these temples and shrines so well versed in religious etiquette. To my mind, the best explanation for their behavior is that they have a genuine interest in religion.

Millennial Cults of the 1970s

The shin shūkyō (new religion) that thrived in the heyday of rapid economic growth and urbanization lost momentum during the 1970s, particularly after the economic slowdown precipitated by the oil crisis of 1973. Sōka Gakkai’s problems were exacerbated by a wave of bad publicity in the media following its attempt, during 1969 and 1970, to suppress the publication of a book harshly critical of the organization.

As the shin shūkyō stagnated, a new crop of cults and sects sprang up to fill the gap. These were dubbed shin shin shūkyō, or “new new religions.” One of the major forces shaping the religious movements of the 1970s was a surge in apocalyptic and millennial thinking, epitomized by two of the top-selling books of 1973, Nosutoradamusu no daiyogen (Prophecies of Nostradamus) and Nihon chinbotsu (Japan Sinks). Where the shin shūkyō of the 1950s and 1960s had promised the worldly benefits of health, wealth, and peace, the shin shin shūkyō (new new religions) emphasized the approaching “end times” and promised followers the ability to survive the apocalypse.

Buddhism too has benefitted from the upturn in religious sentiment amongst the young

As in the 1950s and 1960s, the rise of these new orders and cults was fueled predominantly by young seekers. This time, however, the majority of converts appear to have been individuals born and raised in or around major urban centers, as opposed to recent migrants from the countryside. Simply put, they were the children and grandchildren of the generation from which the shin shūkyō had drawn their membership. Among the more prominent of these apocalyptic and millennial movements were Mahikari, GLA, and Agon Shū, as well as the overseas-based Unification Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The 1970s were also marked by concerted efforts on the part of the established shin shūkyō to compete with the shin shin shūkyō in attracting young converts. A good example is the Inner Trip movement launched by the Nichiren lay organization Reiyūkai (from which Risshō Kōsei-kai originally sprang). Sōka Gakkai, meanwhile, began holding youth-oriented World Peace Festivals, conceived as opportunities to organize and draw young people into the fold.

A Return to Traditional Values

Both the lay movements of the rapid-growth period and the sects and cults that emerged subsequently have lost ground in recent years. Religious groups of this sort have little appeal for today’s youth.

Sōka Gakkai, which used shakubuku (break and subdue) so effectively to build the organization during its heyday, now relies almost entirely on the children of existing members to replenish its ranks. The newer-style cults, similarly, have lost their impact and vitality and rarely come up in the media. In the realm of religious studies, the term shin shin shūkyō (new new religions) has virtually fallen out of use. With the passage of time, the phenomenon has been subsumed under the general category of shin shūkyō (new religions). And nowadays, shin shūkyō seems anything but new.

Cults and spiritual movements tend to exert a powerful appeal during times of social upheaval, when rapid change breeds deep uncertainty about the future. To be sure, the past few years have witnessed some traumatic events, including the 2008 financial meltdown and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. But notwithstanding these setbacks, Japanese society as a whole is considerably more stable and predictable than it was during the period of rapid economic growth or the economic bubble of the 1980s. In terms of political and social stability, the Heisei era (1989–) thus far bears comparison with the Heian (794–1185) and Edo (1603–1868) periods.

Meiji Jingu: "the lush forest setting in which the shrine is situated helps convey a truly timeless Japanese spirituality."

In such times, traditional and conservative impulses tend to predominate. In the realm of religion and spirituality, this impulse is manifested as a preference for faiths that have stood the test of time, rather than new religions or cults.

Japan’s established religions are among the oldest in the world. Shintō goes back thousands of years, and while it has evolved considerably over time, its longevity and continuity as a system with its roots in primitive folk belief are probably unequaled.

Buddhism cannot be considered an indigenous religion, having entered by way of China and the Korean Peninsula, but its history in Japan goes back almost 1,500 years, to the middle of the sixth century. Since then, Buddhism has lost ground in China and Korea and has all but vanished from India, where it originated. Japan is one of only a handful of places, including Tibet and Vietnam, where Mahayana Buddhism persists as the dominant religion today.

Ise Shrine’s shikinen sengū rebuilding ceremony dates back to the end of the seventh century. Nara and Kyoto are brimming with magnificent monuments to Japan’s ancient religious heritage, Buddhist and Shintō alike. Because Japanese spirituality is inextricably connected with nature, most of these religious sites stress the natural environment in some way, and this element of nature worship accentuates the continuity with ancient religion. Tokyo’s Meiji Jingū, for example, dates only to the 1920s, but the lush forest setting in which the shrine is situated helps convey a truly timeless Japanese spirituality.

It seems to me that, to today’s young people, these ancient traditions offer something new and refreshing. I would suggest that their efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into those traditions.

The nostalgic and conservative impulses underlying this trend are apparent as well in the political orientation of today’s young people. Amid rising political tensions between Japan and its neighbors in the region—particularly China and South Korea—these impulses tend to arouse an intense nationalism. Such feelings are exacerbated by Japan’s current sense of stagnation. Without the endless possibilities offered by rapid social change, the younger generation becomes restless and unconsciously looks forward to some dramatic event or development to relieve the boredom.

For an impulse to gel into a movement requires the leadership of some charismatic figure. It is doubtful that Sōka Gakkai would have grown into such a huge religious community had it not been for two such leaders, Toda Jōsei and Ikeda Daisaku. Likewise, there would have been no Aum Shinrikyō without Asahara Shōkō. Whether a comparable figure will emerge again any time soon is impossible to say. But in today’s climate, the emergence of a charismatic leader capable of focusing the inchoate spiritual longings of today’s youth may be all that is needed to give rise to a major new religious movement in Japan.

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”

“Efforts to honor shrine and temple etiquette reveal an intuitive understanding that adhering to established ritual is the only way to truly enter into ancient traditions.”

Hirano Jinja is one of thirteen Kyoto shrines in Cali and Dougill’s Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion (Univ of Hawaii, 2013). From that we learn the shrine was founded in 782 in Nara, before being relocated to the new capital of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 794. The present buildings date from 1625, and with their unpainted wood and cypress-bark tiles they present an evocative rustic appearance.

Hirano Jinja is one of thirteen Kyoto shrines in Cali and Dougill’s Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion (Univ of Hawaii, 2013). From that we learn the shrine was founded in 782 in Nara, before being relocated to the new capital of Heiankyo (Kyoto) in 794. The present buildings date from 1625, and with their unpainted wood and cypress-bark tiles they present an evocative rustic appearance.