Kumano Hayatama Taisha, one of the Big Three Shrines in the area

Kumano is one of Japan’s most appealing areas, a spiritual heartland and part of a World Heritage site. It’s winning increasing attention from tourists, particularly for the opportunities for trekking and hot springs. In the article below, from the Japan Times, Alon Adika highlights the religious and syncretic heritage of the region.

***********************************************

By ALON ADIKA (Japan Times, Jan 11, 2014)

An old tale from Kumano tells of a hunter who was out one day with his dogs when he spotted a large boar. Stretching his bow, he took aim and loosed an arrow deep into the body of the beast. With its last strength, the boar fled and led the hunter to a yew tree at Oyunohara, where it lay down and died. After gorging on its flesh, the hunter fell asleep under the tree, only to waken in the night to see that three moons — which revealed themselves to be manifestations of the three Kumano deities — had descended onto the tree.

Those gongen — native gods that merge indigenous beliefs with avatars of Buddhist deities — remain to this day as intrinsic to the verdant mountains of the Kumano region of the Kii Peninsula straddling parts of Mie, Wakayama and Nara prefectures as its rushing rivers, towering waterfalls and magnificent Pacific Ocean coasts.

The Buddhist pagoda overlooking the sacred Shinto waterfall of Nachi

Considered since time immemorial a mystical realm where the boundaries of the celestial and terrestrial worlds are blurred, Kumano — now a Unesco World Heritage Site — has for a millennia and more been crisscrossed by a network of pilgrimage routes. As well as linking with the ancient capital of Kyoto and other sacred sites in the Kansai region of Honshu, these routes also connect the Kumano Sanzan, the Three Grand Shrines of Kumano — Hongu-Taisha, Nachi-Taisha and Hayatama-Taisha.

But no matter how splendid the Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, in Kumano it’s nature that commands center stage. When I left Osaka in the early morning, it was overcast and a little cool. By the time I reached Nachi Station, a light but steady rain was falling. I got off a local bus at Daimonzaka, from where it was just a short walk to Nachi Grand Shrine on a well- preserved portion of the pilgrimage route.

Two large trees flanked the stone path, like a natural gate into the forest. The rain had turned the forest into an enchanting place: the patter of raindrops hitting the dark-green leaves, the slick and shiny stone path and the old trees towering above me made me feel like I had been transported to a different time and space.

After visiting the shrine, I fixed my eyes on the mountain face across from me. I knew it was there; I had seen it in photographs numerous times. However, through the heavy mist, I could not see it. Then, as if someone had waved a magic wand, the mist dissipated and the powerful Nachi Falls were revealed, thundering down a 133-meter cliff and pounding the pool below.

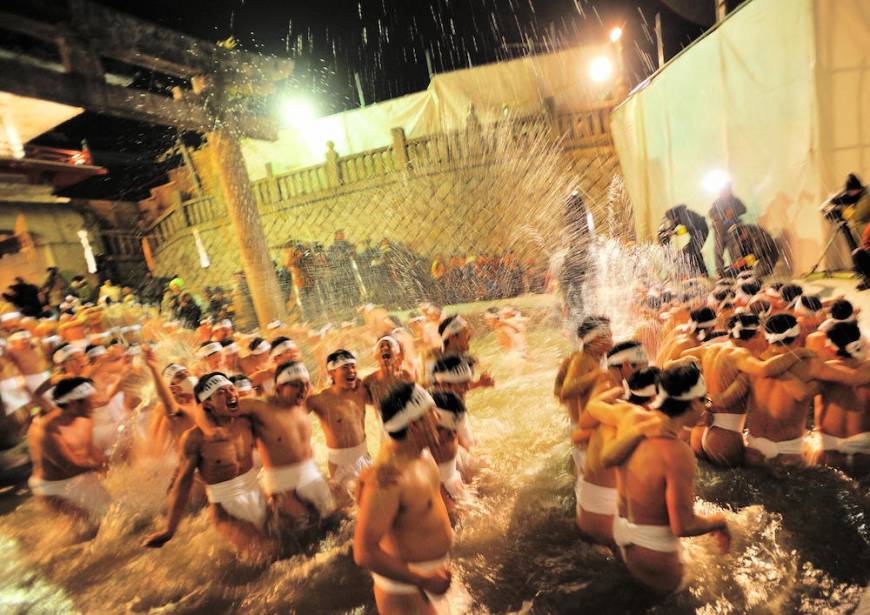

Kumano eventually became an important training ground for holy men and followers of Shugendo, a syncretic faith that fused native Japanese animism, Buddhism and elements of Taoism. They practiced mountain asceticism to gain spiritual and supernatural power.

Legend has it that in the 11th century, the renowned and much-pictured monk Mongaku sat under Nachi Falls in the dead of winter and was saved from certain death only by divine intervention. In more recent times, Hayashi Jitsukaga, a Shugendo practitioner, flung himself over the lip of the waterfall after a session of zazen meditation in 1884. When his fellows found him in the pool below, it’s said his body was still in the zazen position.

Kamikura Shrine with the sacred Gotobiki rock onto which the Kumano kami descended

Thus fortified, late in the afternoon I made my way through the slick streets of Shingu to the Kumano Hayatama Grand Shrine. It was nearly 6 p.m. and the shrine was empty save for a few attendants getting ready to close it for the night. As I admired the shrine, a mother and daughter entered and paid their respects silently in front of the dripping roofs.

I was searching for a sacred boulder, the Gotobiki Iwa: another legendary landing spot of the Kumano deities, which was also the original site of the Hayatama Shrine. A young attendant gave me directions and a map. It didn’t look very far, but little did I know it was up a mountain.

Behind the Shinto gate, a stone stairway led up the hill, the steep and irregularly sized steps seemed never ending. The stones were slippery from the rain and the sun was already low in the sky. Nobody else was around. The combination of the rain, dense foliage and the waning light all made for an eerie atmosphere. Several times I stopped and pondered turning back, only to force myself onward. I later learned there are more than 500 steps up to Kamikura Shrine and the sacred rock.

At the top, a clearing opened up and I saw the great boulder in front of me. It seemed about the size of a small house and was roundish in shape. One explanation for the “gotobiki” in its name, meaning “toad” in the local dialect, is that it supposedly resembles one. I took out my camera and tried awkwardly to take some pictures while still holding up my flimsy umbrella. After a short while, I started making my way back down, not wanting to be on the mountain alone in the dark.

The roofline of Hongu Taisha in springtime, one of Kumano's Big Three Shrines

Relieved to be back in town, I walked through its nearly deserted shopping arcade in search of some dinner. It was only a little after 7 p.m., but most of the shops were already shuttered and the few still open were preparing to close. I ended up getting something from a bento (boxed-lunch) shop and returned to the small Japanese-style hotel I’d checked into earlier.

The next morning I headed off to Hongu, the third of the Kumano Grand Shrines that I’d just learned also have a dim and distant association with the early gods Izanami (Nachi) and Izanagi (Hayatama) who created the Japanese islands — while Hongu itself boasts a bond with Susanoo, the son of Izanagi and mischievous brother of Amaterasu, the sun goddess.

As I again wanted to approach the sacred site on foot via one of the old pilgrimage paths, I took a bus to Hoshinmon Oji, about 7 km distant from it. In contrast to the day before, the skies were deep blue and the sun was shining brightly.

Pilgrimage routes run through the thickly wooded Kumano hills

I first passed through a small mountain hamlet. The buzz of a lawn mower echoed through the valley. There were some unattended stalls, with local products for sale, by the sides of the street. Most had the salty and sour Wakayama umeboshi (pickled plums), which are supposed to be especially tasty.

The path next took me into the woods. Patches of sunlight created a dazzling chiaroscuro on the ground. After a while, the forest, with its scent of damp earth and wet wood, abruptly ended at a road that cut it in two. On the other side in front of a wooden shelter an elderly lady sat by her stall.

I approached and pointed to the succulent-looking cucumbers she had on ice. After choosing one for me, the woman peeled off some of the skin and sprinkled salt onto the fruit. I was just about to take a bite when she had me hold it out and drizzled some honey on top. It was so good that I devoured it in no time — and then had another.

I reentered the forest and took a small detour to a clearing from where I could view the giant torii gate at Oyunohara in the valley below: the place where, in the ancient legend, the Kumano gods revealed themselves to the hunter. Oyunohara is the original site of the Hongu Grand Shrine, which now stands nearby on higher ground after being damaged in a flood in 1889.

Arriving there was somewhat anticlimactic after walking through Kumano’s magical landscape. I had originally planned to walk much more on the old paths and I felt some regret I had not been able to do so. On the train back to Osaka, I studied the pamphlets and maps I had collected, and began planning a future visit I knew I would have to make.

…

A trip to Kumano requires planning. The following websites will help get you started: tb-kumano.jp/en; hongu.jp/en;nachikan.jp/en; kumano-shingu.com

One of the largest torii in Japan, marking the original site of Hongu Taisha before it was washed away in floods

Green Shinto previously carried

Green Shinto previously carried

The piece below comes from the introduction to

The piece below comes from the introduction to