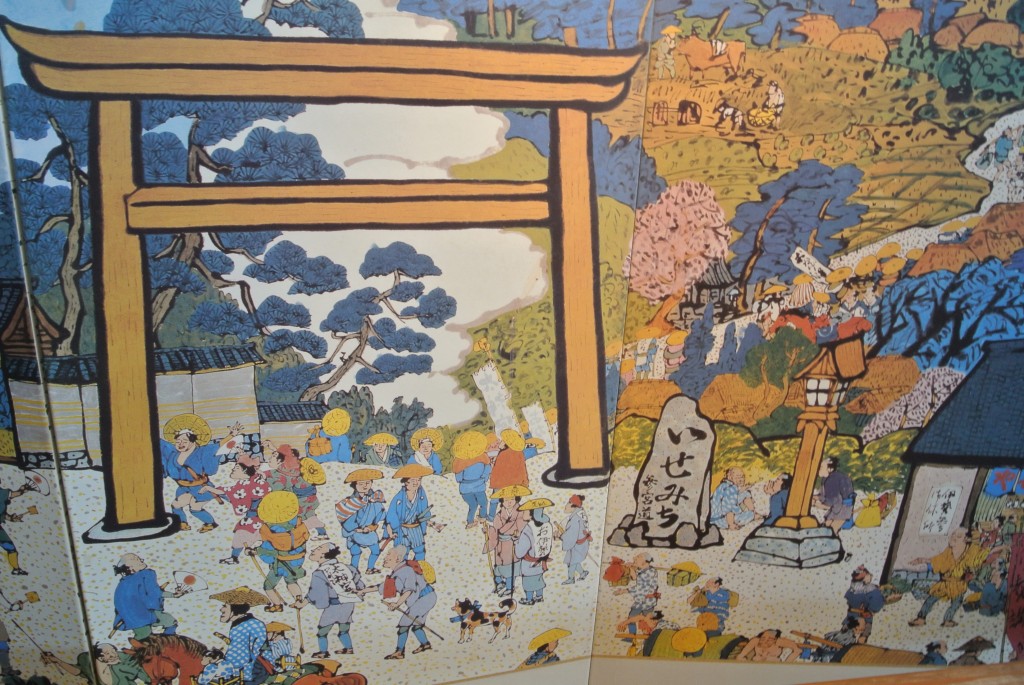

Ise pilgrimage in Edo times – the rich got to ride horses, others paid to have their belongings carried, while those incapable of making the pilgrimage sent dogs in their stead

In the Japan Times this week Green Shinto friend, Amy Chavez, has been writing about the Kumano pilgrimage route. It centres around the three great Shinto shrines known as the Kumano Sanzan. The network of trails is deeply syncretic, embracing several Buddhist sites too including the well-known Koyasan headquarters of the Shingon sect.

It’s said that pilgrimage is the largest collective human enterprise on earth, in which some 300 million people worldwide are engaged each year. Christians do it; Muslims do it; Hindus do it (and even birds do it, if you include migration as a form of pilgrimage!). A quarter of a million people go on the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage each year, while 2-3 million do the Haj to Mecca (one of the five pillars of Islam). But even these numbers are dwarfed by those who undertook the Ise pilgrimage in Edo times, when religion was one of the few valid reasons for travel.

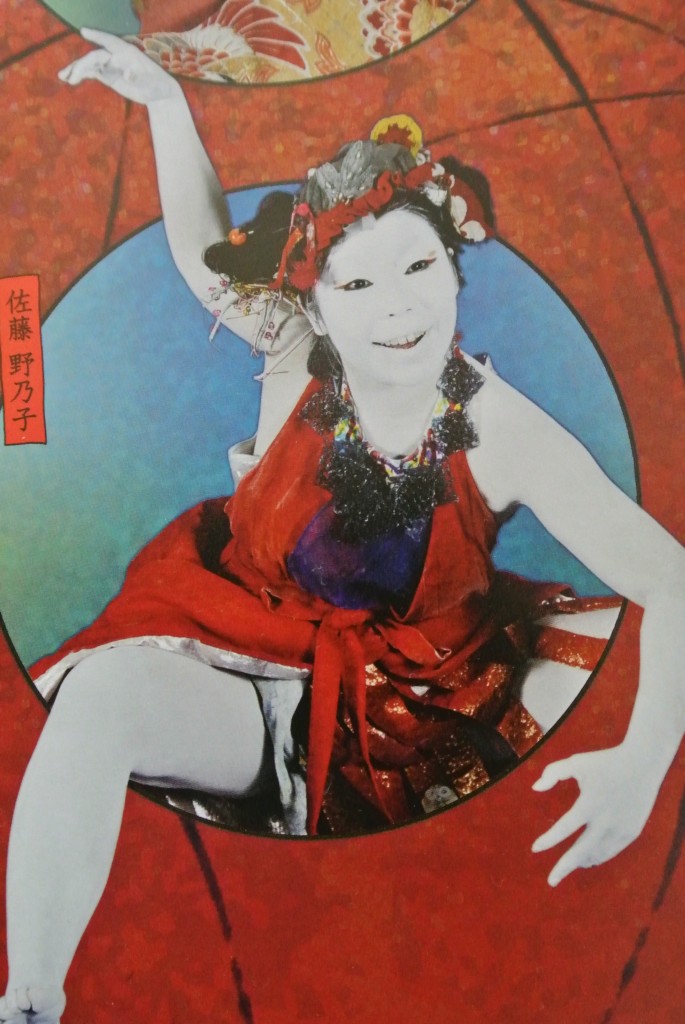

Pilgrimage to Ise in Edo times meant being part of a jostling throng headed for the Outer Shrine (Geku) and the nearby worldly pleasures

The appeal of pilgrimage in modern times goes along with the increasing tendency for people to seek spiritual fulfilment outside the confining rules of religion. The reluctance to join a religion stems from the barriers it creates with an ‘us and them’ mentality. On the other hand, people can take up pilgrimage any time they want without any commitment to a religion. They are free to come and go at their own pace. The destination provides a goal, and there is a tremendous sense of achievement in accomplishing it. When done properly, it can be transformative.

In setting out the pilgrim is embarking on a journey that takes them out of the mundane world of everyday cares and away from their comfort zones. It’s a journey that can make people confront themselves and look inward even as they look outward to the new surroundings. From anticipation and excitement, the pilgrim is led to introspection and self-examination. Physical pain and fatigue are accompanied by downbeat moments of despondency. Like any spiritual journey, the dark moments must be passed through in order to see the radiance at the end of the tunnel.

Modern pilgrimage in Japan often involves transport such as coaches, which could be seen as a symptom of the softness of contemporary life. But walking is an integral part of the process of pilgrimage. It forces the individual to slow down to a meditative pace, and the mind learns to get in step with the regular beat of foot against earth. It’s not by chance that writers and artists often get their best ideas when walking.

Along the way there are chance encounters, and every pilgrim’s story includes serendipitous meetings and chance remarks that prove enlightening. There are life-changing conversations with complete strangers, eager to recount the meaningful experiences they’ve undergone. And there’s a sense of camaraderie in the shared suffering.

Done properly then, the pilgrimage can marry the best of collective experience with the quest for individual enrichment. Shinto pilgrimages in particular often involve journeys into mountains, where the human spirit is refreshed by immersion in raw nature. On returning to reality, everything may seem outwardly the same but the inner self has been purified. The end is but a beginning…

Pilgrims on the Kumano Kodo (Old Pathways), near Nachi Waterfall.

“The function of myth is to put us in sync—with ourselves, with our social group, and with the environment in which we live… One of the most interesting and simple ways to get this message is from the mythologies of the Navaho. Every single detail of the desert in which they live has been deified, and the land has become a holy land because it is revelatory of mythological entities. When you recognize the mythological aspect of Mother Nature, you have turned nature itself into an icon, into a holy picture, so that wherever you go, you’re getting the message that the divine power is working for you. Modern culture has desanctified our landscape and we think that to go to the holy land we have to go to Jerusalem. The Navaho would say, ‘This is it, and you’re it.’ ”

“The function of myth is to put us in sync—with ourselves, with our social group, and with the environment in which we live… One of the most interesting and simple ways to get this message is from the mythologies of the Navaho. Every single detail of the desert in which they live has been deified, and the land has become a holy land because it is revelatory of mythological entities. When you recognize the mythological aspect of Mother Nature, you have turned nature itself into an icon, into a holy picture, so that wherever you go, you’re getting the message that the divine power is working for you. Modern culture has desanctified our landscape and we think that to go to the holy land we have to go to Jerusalem. The Navaho would say, ‘This is it, and you’re it.’ ” “How, in the contemporary period, can we evoke the imagery that communicates the most profound and most richly developed sense of experiencing life? These images must point past themselves to that ultimate truth which must be told: that life does not have one absolutely fixed meaning. These images must point past all meanings given, beyond all definitions and relationships, to that really ineffable mystery that is just the existence, the being of ourselves and of our world. If we give that mystery an exact meaning we diminish the experience of its real depth. But when a poet carries the mind into a context of meanings and then pitches it past those, one knows that marvelous rapture that comes from going past all categories of definition. Here we sense the function of metaphor that allows us to make a journey we could not otherwise make …”

“How, in the contemporary period, can we evoke the imagery that communicates the most profound and most richly developed sense of experiencing life? These images must point past themselves to that ultimate truth which must be told: that life does not have one absolutely fixed meaning. These images must point past all meanings given, beyond all definitions and relationships, to that really ineffable mystery that is just the existence, the being of ourselves and of our world. If we give that mystery an exact meaning we diminish the experience of its real depth. But when a poet carries the mind into a context of meanings and then pitches it past those, one knows that marvelous rapture that comes from going past all categories of definition. Here we sense the function of metaphor that allows us to make a journey we could not otherwise make …”

With their splashes of white and beady intelligent eyes, the seagulls skim at dizzying speeds up and down the river, mostly in large groups but sometimes in pairs or singly. As the day darkens, they whirl up into a dizzying spiral that reaches up to the very heavens before flying off to bed down for the night at Lake Biwa. My heart leaps up when I see them, though I’m none too glad of the cold that clings to them from their Siberian north. (I was once delighted to find on my winter break in Kunming in the Yunnan Province of China that the Siberian seagulls migrate there too.)

With their splashes of white and beady intelligent eyes, the seagulls skim at dizzying speeds up and down the river, mostly in large groups but sometimes in pairs or singly. As the day darkens, they whirl up into a dizzying spiral that reaches up to the very heavens before flying off to bed down for the night at Lake Biwa. My heart leaps up when I see them, though I’m none too glad of the cold that clings to them from their Siberian north. (I was once delighted to find on my winter break in Kunming in the Yunnan Province of China that the Siberian seagulls migrate there too.)

In ancient times, both boys and girls would be shorn of their hair until they turned three, when a formal ceremony would be held after which they were allowed to grow it out. There was also a ritual for five-year-old boys in which they would put on a hakama for the first time. For seven-year-old girls there was the ritual of replacing the narrow belt of a child’s kimono with the much wider obi.

In ancient times, both boys and girls would be shorn of their hair until they turned three, when a formal ceremony would be held after which they were allowed to grow it out. There was also a ritual for five-year-old boys in which they would put on a hakama for the first time. For seven-year-old girls there was the ritual of replacing the narrow belt of a child’s kimono with the much wider obi.