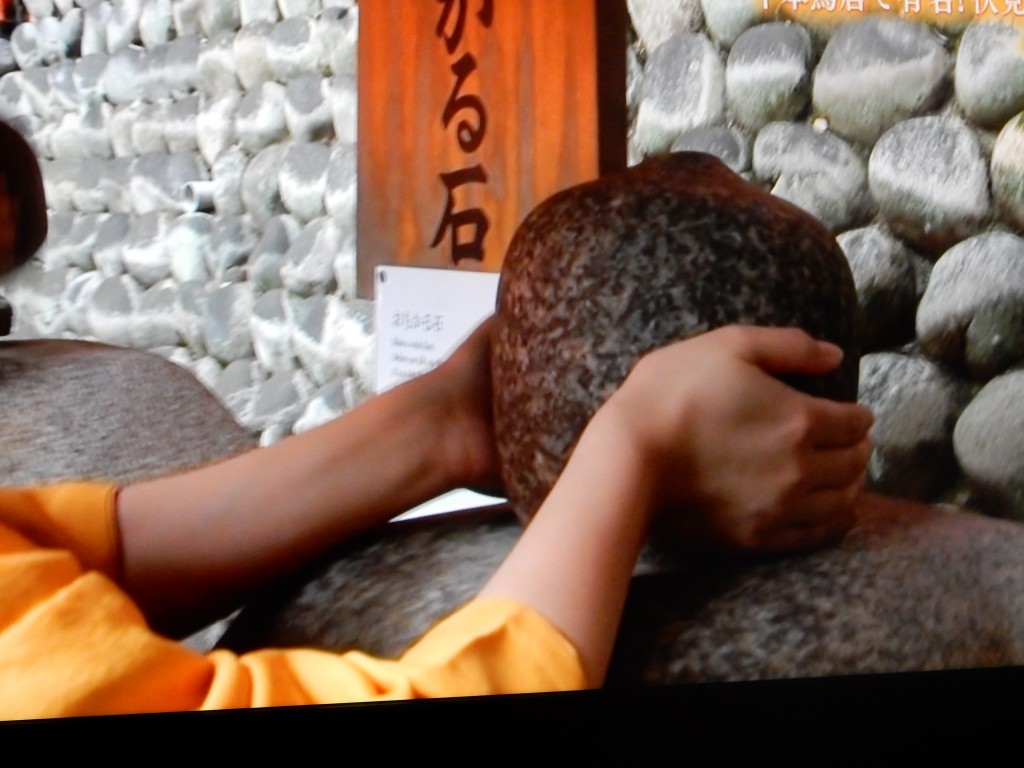

A happy visitor to the shrine's famous power stone, passing through which helps cut bad relationships and form good new ones

Yasui Konpira-gu is one of Green Shinto’s favourite shrines.

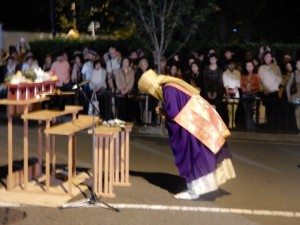

Mochitsuki, or making rice cakes.

It’s in the heart of Kyoto, next to Gion’s traditional geisha era. It’s small but full of history, and it houses the country’s first ema museum. It is famous for its enkiri enmusubi ‘power rock’. And it hosts a wonderful Kushi Matsuri (Comb Festival) featuring the gorgeous hairstyles of Japanese women down a millennium of changes.

Squeezed into an L-shaped space, the shrine leads from the geisha houses of Gion towards the streets running up to Kodai-ji and Kyoto’s Kiyomizu tourist area. The shrine is noticeably sandwiched between love hotels at both its entrances, appropriate for a place which prides itself on promoting happy relationships.

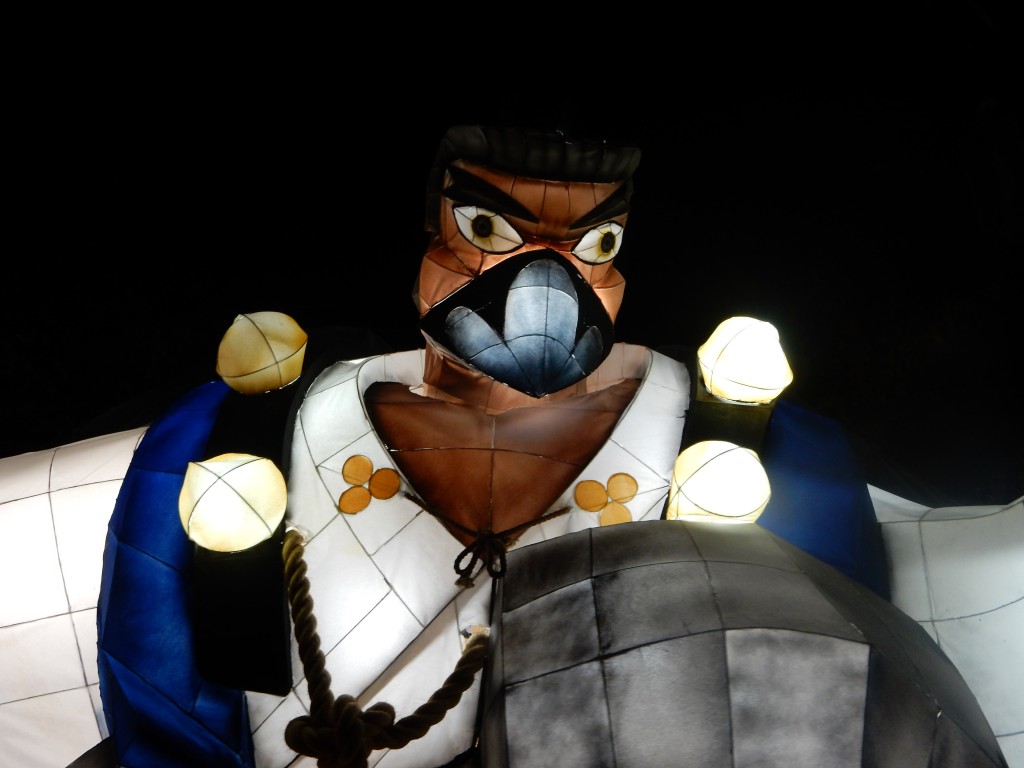

Last weekend was the annual Taisai (main festival) of the shrine, when its mikoshi (portable shrine) is paraded around the parish (there’s a fully illustrated report of last year’s event here).

This year I attended the community event on the day prior to the parade, featuring mochitsuki (making rice cakes). There was a pleasant relaxed atmosphere, which allowed me to explore some of the shrine’s unusual features while talking to the locals and learning of the folklore.

Below follows a listing of 7 striking features I came across in the charmed small compound of the shrine.

1) The entrance torii, unusually, has square pillars instead of round ones.

View from inside the entrance torii with its square pillars, looking towards the east

The slogan across the torii advertises the shrine as a place to sever bad ties and make good new ones

2) Thanks to the recent boom in ‘power spots’ and ‘enmusubi’ (good ties), the shrine has got popular at weekends.

The queue to crawl through the shrine's 'power rock' can stretch all the way down the approach and past the adjacent love hotel.

3) The power rock has a crack running down from the top through which ‘cosmic energy’ passes down into the circular hole through which crawl those wishing to cut off bad ties and make new happy ties.

There's a special spot to stand respectfully before crawling through the hole

You have to be a certain shape and flexibility to slip through so easily

Being reborn to a better life is cause for celebration

3) The Comb Mound (Kushizuka) is relatively recent. Contrary to expectations, the burial mound to pacify used and discarded combs is not ancient but was (re-)created by a scholar in the Showa era. His statue can be seen next to the mound.

The Comb Mound and the scholar whose ideas led to its creation

4) There’s a fantastic dragon carving in the honden (sanctuary). Most people only get to see the Worship Hall (haiden). However, if you take the trouble to look behind it and into the honden building, you’ll see a magnificent ranma carving featuring a dragon.

Hiding in the rafters of the Honden (Sanctuary) is this superb dragon

5) There’s a ‘distant prayer’ shrine facing towards the main Konpira shrine in far-off Shikoku.

The shrine faces towards Kotohira-gu, known as Konpira-san, in Shikoku

6) There’s a Buddhist-style subshrine, most unusually. Inside is a Buddhist bell and incense set before the statues of eight sumo-style figures, representing strength. They are carved from the base stones (‘strength stones’) which supported the massive pillars of the temple to which Yasui Konpira-gu was attached prior to the enforced separation from Buddhism at the beginning of the Meiji Era in 1868.

The shrine of the 8 strong men is a legacy of the temple-shrine complex to which Yasui Konpira-gu once belonged

inside are eight sumo style strong men, carved out of the pillars of the former Buddhist temple that once stood nearby

7) The shrine claims to have Kyoto’s oldest existing komainu, by its northern entrance. I would like to get that confirmed because they’re surprisingly not that old, dating back to the middle of the Edo Period. The faces are worn, but one can make out the closed mouth (yin) and open mouth (yang), and no doubt these fierce creatures are still vigilant enough to see off any evil spirits trying to lurk into the shrine.

************************************************

For a full page report of the shrine by Hugo Kempeneer as part of his Kyotodreamtrips.com site, please click here. The page also contains a video of the Comb Festival, which takes place in September and features a parade of women’s hairstyles and fashion over the past millennium and a half.

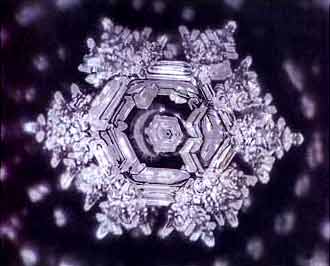

Sadly, news has come of the demise of Dr Emoto, whose water crystal photography stunned many and raised awareness of the damage done by pollution and negativity. Here is a statement from Michiko Hayashi, his Personal Assistant.

Sadly, news has come of the demise of Dr Emoto, whose water crystal photography stunned many and raised awareness of the damage done by pollution and negativity. Here is a statement from Michiko Hayashi, his Personal Assistant.