Anyone interested in nature worship will also be concerned with conservation. In this respect there is one easy way in which to help protect the natural world, and that is by simply clicking your mouse every morning on the website described below. By this one simple action, you can help preserve rainforests and endangered species. The explanations below provide the rationale and a description of how it works.

******************************************************

EcologyFund is owned and operated by The Hunger Site Network as a way to get new funds for critical habitat and wilderness preservation using the power of the internet. When you “click to give” our sponsors pay the project you selected to preserve the number of square feet shown by each project. You pay nothing.

To maximize the contribution, click on each project every day. If you register, The Hunger Site Network will donate 500 square feet of wilderness in your name, and will keep a running tally for you of all the land you have preserved. Other sites owned and operated by The Hunger Site Network are The Hunger Site, The Breast Cancer Site, The Rainforest Site, The Animal Rescue Site, and GreaterGood.com.

All monies from sponsorships generated on EcologyFund go to purchase and protect wild lands. Sponsors are interested in supporting wilderness preservation for the same reasons we are: 1) its good for the environment, 2) our advertising budgets can do double duty and accomplish something important, and 3) the best form of public relations is good work.

If you click and visit a sponsor’s site it will usually double their contribution. Clicks to site advertisers in our Special Donations section will save additional land or plant trees. Certain actions (ordering free catalogs or registering for free) will save even more land or plant additional trees through our Rainforest Rewards section. Shopping through Shop For Acres will save an average of 50 square feet per dollar spent. The average amount of land protected through each action of the site is always specified. A breakdown of the amount contributed is listed in our totals section.

Click here for the Ecology Fund

*********************************************************

Testimony to the effectiveness of the Ecology Fund follows below written by the World Pantheism Movement, of which I am a member…

******************

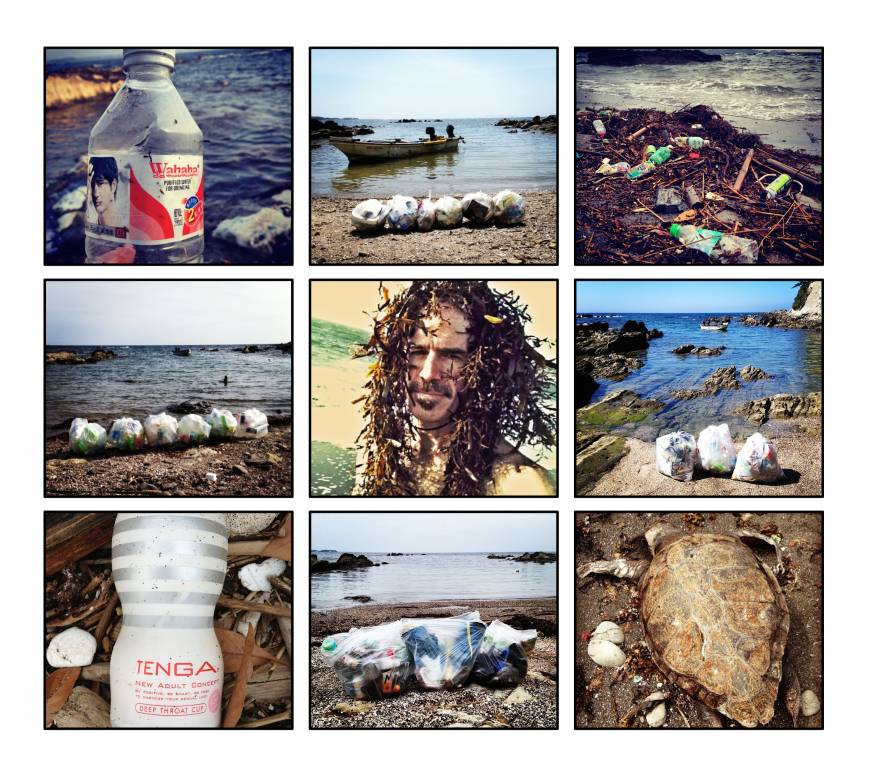

Nature can be tenacious, but it needs our help from the predations of mankind

The WPM has saved more than 100 acres of natural wildlife habitat from destruction through our click group at EcologyFund, and an additional 75 acres through sponsorship of click schemes at EcologyFund and Care2. Most of this land is rainforest brought under the protection of conservation organizations in Central America.

We currently focus our efforts on EcologyFund, where we have a click group with over 1,200 members. We have saved more land than any other religious or environmental group on the site (including Sierra Club and WWF groups), and even more than some groups listed in the top ten.

How it works

Each person who clicks every day, at the current total of 87 sq ft per day, can save almost three quarters of an acre (almost 32,000 sq ft) of wildlife habitat per year from development or exploitation!

This has benefits for the climate as well as for biodiversity. If this area were cleared for farming, it could emit carbon dioxide equal to what the average American produces in half a year – or an average European in a full year. Your daily clicking can prevent that from happening.

Rainforests are the most biodiverse habitats on earth. Just one acre contains around 300-400 individual trees of 20-80 different species, and each tree is home to thousands more species. One tree in Peru was found to house 43 different species of ant.

Who pays for it?

Each page of the site shows ads for eco-friendly companies and non-profits. The income from these advertisements is given to nature conservation organizations. These organizations in turn buy private land in sensitive areas and dedicate the land in perpetuity to wildlife habitat. Basically, your clicking stimulates organizations and companies to spend money on conserving wildlife habitat. You can increase their gifts by visiting, and perhaps even buying from or otherwise supporting an advertised site that catches your eye.

How do I know this is for real?

The World Pantheist Movement has direct experience that it works, because we have advertised with EcologyFund in the past. Our check was always addressed and sent directly to the conservation organization we wished to sponsor – in our case the Rainforest Trust (formerly World Land Trust USA). EcologyFund did not take a cut. World Land Trust undertakes to preserve one acre of habitat for every $100 donated.

Why participate?

We are an integral part of Nature, which we should cherish, revere and preserve in all its magnificent beauty and diversity. Conserving rainforest is also a matter of survival for millions of humans whose homes and livelihoods may be threatened by sea level rise or climate change.

Of course you can save land on your own – but being in a team that can show visible collective results is a good motivation to stick at it and not forget, and it gives the excitement and satisfaction not only of your own totals but also those of the group.

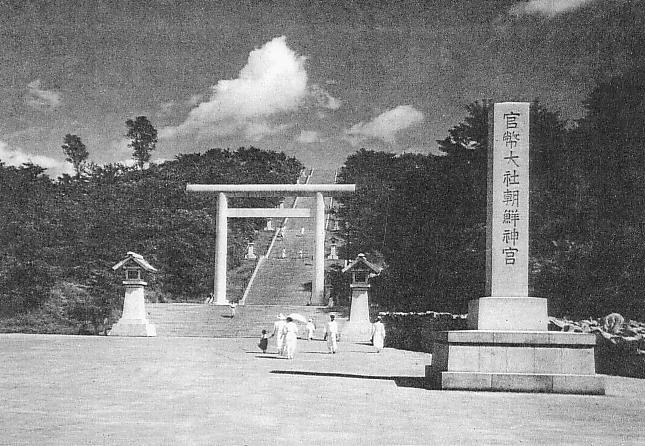

Unspoilt nature in the grounds of the Togakushi Jinja in Nagano