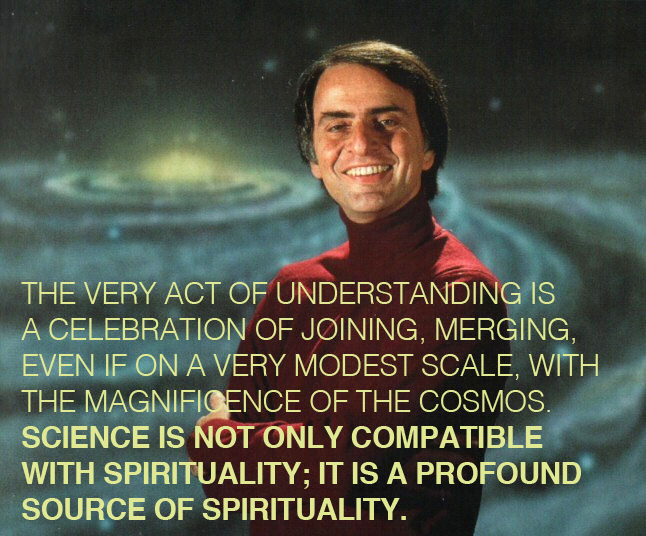

Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) and his one-time mentor and friend, Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850-1935), were both deeply versed in Shinto. I’ve long been fascinated by the differences between them, perhaps because they speak to different parts of my personality. On the one hand is the deeply romantic Hearn, who sought to escape an industrialising present in an idyllic Japan. On the other hand, there is the scholarly Chamberlain, concerned to maintain his commitment to truth.

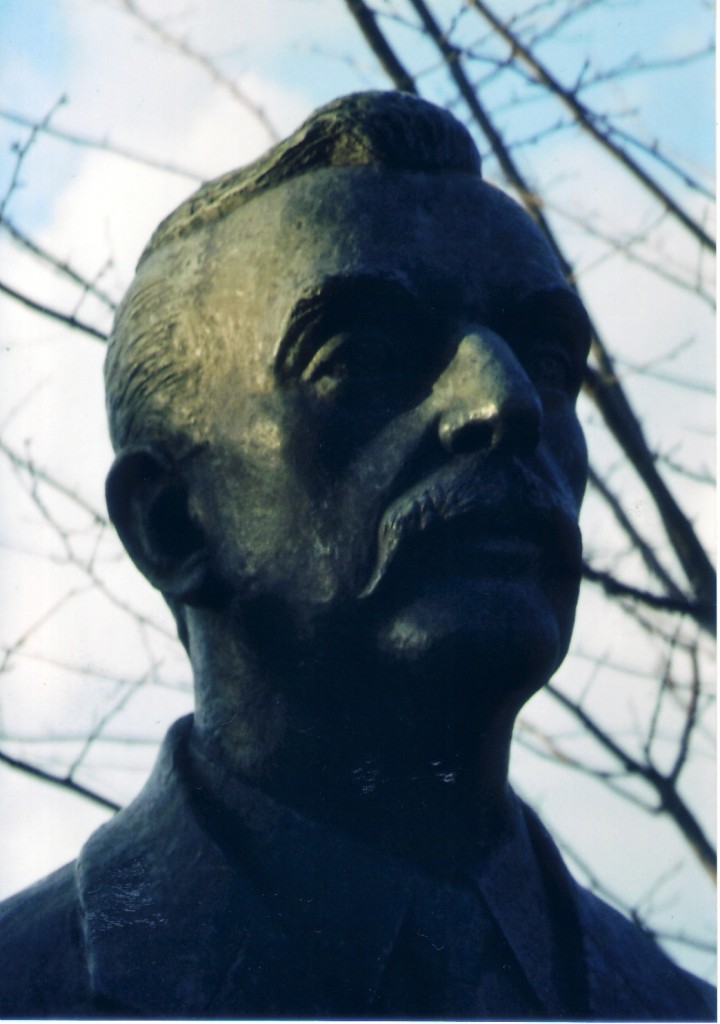

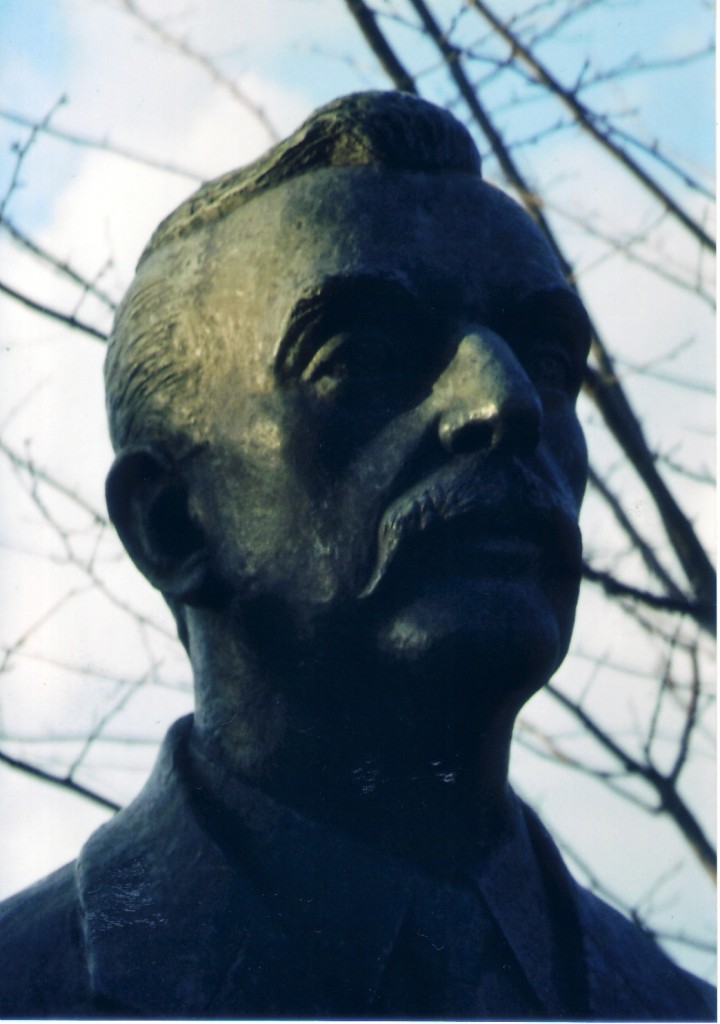

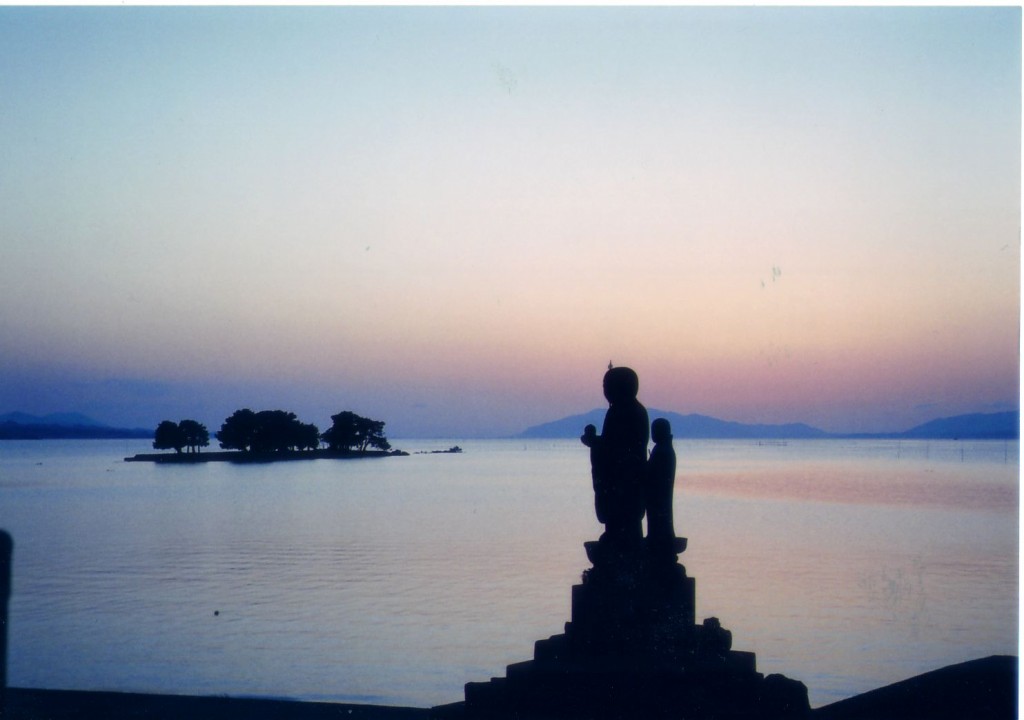

Statue of Lafcadio Hearn in Matsue, Shimane, where he had his first house

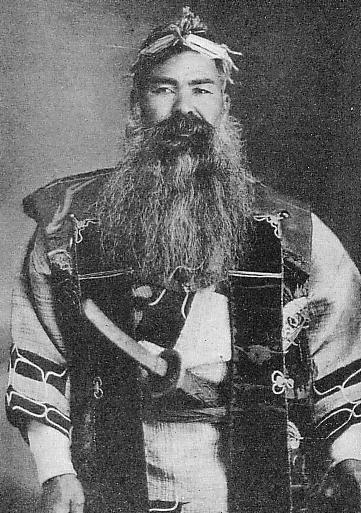

Basil Hall Chamberlain, one-time good friend and mentor to Hearn

Hearn married a Japanese and went native; yet though Chamberlain was the more fluent linguistically (he famously taught Japanese to the Japanese themselves), he clung to his British identity. In contrast to Hearn’s enchantment with folklore, Chamberlain remained detached in his compilation of the voluminous Things Japanese (1890-1906).

It was Chamberlain who as professor at Tokyo Imperial University helped Hearn get his first job in Japan. Hearn became more well-known because of his writings, which shaped Western perceptions of the country. He wrote of folk customs and ancestor worship, whereas B.H. Chamberlain translated the archaic Kojiki (1882), a huge achievement but not of such popular appeal. Nonetheless Chamberlain is acknowledged as the most influential translator of Japanese before Arthur Waley (who translated Genji).

The Japanese adopted Hearn as one of their own, as indeed he was after being naturalised as Koizumi Yakumo. His house has been turned into a museum, and his great-grandchildren keep his name alive in the public domain. Chamberlain by contrast is little-known among the Japanese. But a century after the influential pair, it seems to me that though Hearn’s writing has a seductive pull, it was Chamberlain who was the more enlightened, as is evident in the paper below. I used to belong to the Hearn persuasion; recently I’m inclining towards Chamberlain.

The garden in Hearn’s house in Matsue of which he wrote so graphically

*********************************************************

New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 3, 2 (December, 2001): 106-118.

INTERPRETING JAPAN’S INTERPRETERS: THE PROBLEM OF LAFCADIO HEARN

NANYAN GUO1 University of Otago

Hearn loved what he thought of as ‘Shintoism’, which in his mind combined various beliefs and practices of the common people with the ideology of the Emperor system, which was being constructed in the Meiji period. This has been emphasised recently by some Japanese scholars who treat Hearn as the non-native person who best understood the traditional culture of Japan.

However, Hearn’s interpretation of Shintoism is problematic. He confused the Shintoism he discovered in Japanese legends and religious sentiment, which fascinated him, with the fanatic nationalism which was then being constructed by politicians and ideologues on Shinto foundations. He seems to know little of the political background to this latter process.

Chamberlain’s translation of The Kojiki opened up the stories of Japanese mythology to the likes of Hearn and other Japanophiles.

Having himself become ‘Japanese’, Hearn’s writings on Japan suffer from his uncritical and excessive embrace of many things ‘Japanese’, and it is this element which makes them susceptible to manipulation in the interests of a different kind of nationalism one hundred years later.

When Japan started to gain confidence from its economic success in recent decades, Hearn’s popularity again rose. During the 1990s, his major works were re-translated, compiled into a six-volume series and published under new titles and in a new order decided by the editor. Frequent re-printings of this pocket-sized series indicate that Hearn is being widely read today in Japan.

The editor, Hirakawa Sukehiro, who is also author of several books on Hearn, argues Hearn was the only Westerner of his generation to pay attention to the importance of Japan’s native religion. Hirakawa believes Hearn wrote beautifully about the Shintoist feelings of the common people and the legends of the world of the dead. Hirakawa also thinks that the re-evaluation of Hearn is part of the process of realizing that Western religion is not superior. Hearn’s frequent praise for Japanese patriotism based on his understanding of ‘Shintoism’ deserves especially careful study.

IGNORING INDIVIDUALITY

In Hearn’s article, ‘From the Diary of an English Teacher’ (in Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan), there is a conversation between Hearn and one of his students from the Middle School of Shimane Province in Matsue regarding bowing before the Emperor’s portrait. Hearn said to the student:

I think it is your highest social duty to honor your Emperor, to obey his laws, and to be ready to give your blood whenever he may require it of you for the sake of Japan. I think it is your duty.

In other words, he was doing no more than repeat what most Japanese teachers were telling their students at this time because they all knew that the Christian essayist Uchimura Kanzö (1861-1930) had been expelled in January 1891 from the First Higher School in Tokyo for failing to show sufficient respect for the signature of the Emperor appended to a copy of the new Imperial Rescript on Education.

Hearn’s house, open to the public, stands next to a museum dedicated to the writer

After quoting Hearn’s advice to his students, Hirakawa Sukehiro repeats that Hearn was able to understand the nationalism of the Meiji period despite being a Westerner, and describes Hearn’s observations as an impressive and accurate understanding of the psychology of Japan (Hirakawa 1996: 23 & 27).

Because Hearn was not able to read Japanese, his knowledge of ‘the psychology of Japan’ came mainly from the people surrounding him, and therefore his judgements and feelings were strongly influenced by them. As we can see from his numerous books, Hearn sympathised with Japan because of his love for the people and the traditional culture, and also because of his resentment of modern Western civilisation and Christianity.

Just like the majority of the Japanese around him, he was overjoyed when the country’s army defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-5) and, as the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5) loomed, he believed that Japan would win that too.

Hearn’s belief in patriotism, based on his love of the ‘Shintoist’ ideal of the sacrificial dead, was strong enough to extinguish his humane emotion [for the war damage]. although Hearn perceived the soldiers’ feelings and felt compassion for the dead, he preferred to choose refuge in the so-called ‘Shintoist’ ideal and to forget about the brutal reality caused by Japanese patriotism.

Things Japanese in a revised edition as Japanese Things remains a lively read and is amazingly still in print (and on Kindle)

A DIFFERENT VIEW OF PATRIOTISM: BASIL HALL CHAMBERLAIN

Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850-1935) – In reply to Hearn’s letter in which he wrote: ‘I could really cry with vexation when I think of the indifference — the ignorant, blind indifference of the Educational Powers — to nourish the old love of country and love of the Emperor’ (11 October 1893) (Hearn 1910: 184),

Chamberlain stated an opposite view:”I do not agree with you that the Gove’t [sic] does nothing to foster patriotism and the old military spirit. What of the new songs & poems published by the authorities for the use of soldiers & students …? What of the prostration at New Year before the Emperor’s picture? What of the students’ military drill? What of the creation of such festivals as the Emperor’s birthday, the late Emperor’s anniversary, the 11th February? To my mind there is far too much jingo patriotism in this country. But then I confess that patriotism, anywhere, is a thing altogether distasteful to my mind … It grows from ignorance, and is nurtured by prejudice.” (22 October 1893) (Chamberlain 1936: 108)

Living in Japan for more than 30 years, Chamberlain also loved the country deeply (Ota 1998: 3-4). He insisted that ‘true appreciation is always critical as well as kindly’ (Chamberlain 1905: 7). In 1912, he wrote a pamphlet for the Rationalist Press Association entitled ‘Bushidö or The Invention of a New Religion’, and in 1927 included this in the fifth edition of Things Japanese. In the pamphlet, Chamberlain pointed out:

“Mikado-worship and Japan-worship — for that is the new Japanese religion — is, of course, no spontaneously generated phenomenon …. Not only is it new, it is not yet completed; it is still in process of being consciously or semi-consciously put together by the official class, in order to serve the interests of that class, and, incidentally, the interests of the nation at large …. The new Japanese religion consists, in its present early stage, of worship of the sacrosanct Imperial Person and of His Divine Ancestors, of implicit obedience to Him as head of the army (a position, by the way, opposed to all former Japanese ideas, according to which the Court was essentially civilian); furthermore, [it consists] of a corresponding belief that Japan is as far superior to the common ruck of nations as the Mikado is divinely superior to the common ruck of kings and emperors.” (Chamberlain 1939; 1985: 81, 87)

In Yuzo Ota’ s book Basil Hall Chamberlain, Portrait of a Japanologist (Japan Library, 1998), Chamberlain is shown to be an excellent example for people of today who wish to be free from a narrow-minded nationalism. This book directly challenges the tendency among some Japanese scholars to rebuke Chamberlain and beatify Hearn. It has provided the opportunity to reconsider Chamberlain in comparison with Hearn without bias.

Compared to Chamberlain, Hearn’s love for ‘Shintoism’ and Japanese patriotism was self-deceiving. As demonstrated above, Hearn was not a single- minded person, but rather was conscious of contradictions inside himself. Being aware of these contradictions, he chose to believe in the ‘Shintoist’ fantasy.

His contradictions also disclose the complexity of his literary imagination, and caution us not to take his interpretations of Japan at face value but to examine them carefully. Ignoring his complexity and simplifying his thought can only lead to a self-serving conclusion. Hearn was a problematic interpreter of Japan who deserves an objective and thorough study.

Hearn has long been praised as a way of praising Japan. In the latter years of the twentieth century, glorification of Hearn’s patriotic love for Japan and for the ‘Shintoist’ ideology of the Meiji period can be seen as a rhetorical device to promote a renewed nationalism, one with similar characteristics to that of a century ago. It was the promotion of such an ideology which led, only half a century ago, to the demand in the name of the Emperor for the blood of the people.

****************************************************

For more about Hearn and his writings on Matsue and Shinto, see this posting here.

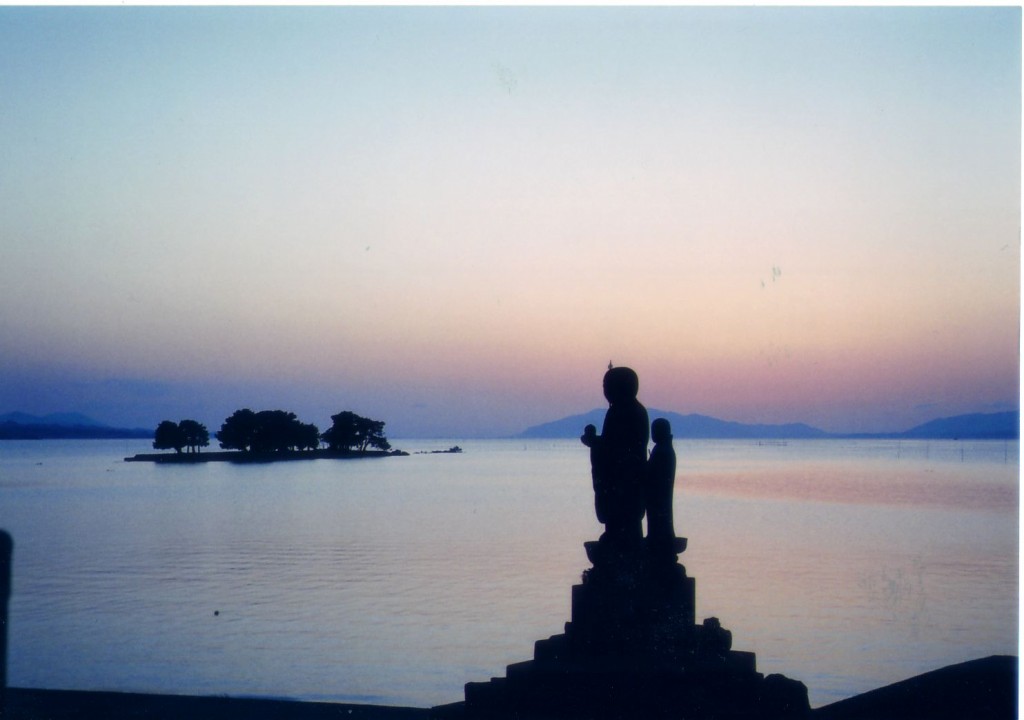

The sun goes down over Lake Shinji at Matsue a century after the Hearn-Chamberlain friendship came to a fractious end