In an essay on environmentalism in Shinto which has appeared recently on the academic.edu website, Green Shinto friend Aike Rots puts forward different ‘paradigms’ used in descriptions of Shinto. It should give pause to those who like to argue for some kind of ‘official’ version of Shinto. The fact is that there are competing versions.

In the first part of the extract below, Aike talks of the rift between the historical-constructivists and the essentialists. This might seem needlessly theoretical, but as Shinto spreads in the West the arguments between practitioners is becoming increasingly split between the two viewpoints. It’s as well to understand what exactly the differences rest upon.

In the second part, Aike writes of identifying ‘six postwar paradigms’, though reading through the passage below there appear to be only five. Perhaps if Aike reads this, he’d be good enough to write in and add to the following: 1) imperial Shinto; 2) ethnic religion; 3) local (folk) religion; 4) universalism; 5) the spiritual approach.

***************************************************

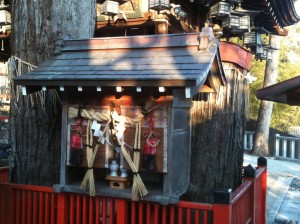

Some consider the kamidana an essential part of Shinto – yet the custom of household kamidana only dates back to the mid-Edo period.

In some ways, defining Shinto is even more difficult than defining Christianity, Islam or Buddhism. Those three religions all somehow trace their own history back to a legendary historical founder – Jesus, Muhammad or Gautama Buddha – and to the period in which this person lived. But when it comes to Shinto, there is very little consensus about when this religion started.

Famously, Shinto has no single founder, and it is not easy to trace it to one single period in history. Some argue that it is has existed since ‘time immemorial’; according to one of most famous and widely read English-language introductions (number one on the amazon.com list, in fact), it is the Japanese ‘native racial faith which arose in the mystic days of remote antiquity’ (Ono 1962, 1).

Among Shinto intellectuals, there is disagreement over the question whether the tradition goes back to the worship practices of hunter-gatherers in the Jōmon period (30,000-300 BCE) or to those of Yayoi-period rice farmers (300 BCE-300 CE). Many serious historians think the tradition was shaped much later, under the influence of Chinese ideology and rituals, and of Buddhism: in the Nara period (8th century), according to some; in the late-medieval period, according to others; or even in the 18th or 19th century, as a modern invented tradition (e.g., Kuroda 1981).

In any case, it is important to realise that there is a difference between two things. On the one hand, there is the historical reality of shrine worship, of the worship of local deities (kami) by means of ritual sacrifice and prayers (norito). These worship practices have always been characterised by great local diversity, constant change, and continuous interaction with Buddhism, Confucianism and Chinese cosmology and ritual.

Local, national, international? Some think kami only exist in Japan (kami no kuni). Originally they were localised, nameless and formless. Only later did they become personified as ancestral spirits.

On the other hand, there is the abstract concept ‘Shinto’, conceptualised as a single and singular tradition, which symbolically unifies the Japanese people as a nation and which is often seen as intimately connected with the imperial institution.

As my PhD supervisor Mark Teeuwen once wrote: Shinto ‘is not something that has “existed” in Japanese society in some concrete and definable form during different historical periods; rather, it appears as a conceptualization, an abstraction that has had to be produced actively every time it has been used’ (2002, 233). But this abstract concept has not always carried the same meaning, and it does not mean the same thing for different people.

There is not only the difference between the ‘insider’s view’, which holds that Shinto is the

indigenous worship tradition of the Japanese people; and the more critical ‘outsider’s view’, according

to which Shinto is an abstraction – and one that appeared fairly late in history. I call this latter approach the historical-constructivist approach.

Most historians today subscribe to this approach: they distinguish between the abstraction ‘Shinto’ on the one hand, and the historical diversity of kami worship on the other, and they deny that there is any transhistorical essence to Shinto (i.e., something that defines ‘Shintoness’). This is different from most insiders’ interpretations, and from most popular introductions to Shinto, which usually assert that Shinto is the indigenous religious tradition of Japan – singular, ancient, uniquely Japanese, and with an unchanging core essence. That is why I call these approaches ‘essentialist’.

But there are also significant differences between various insiders’ interpretations. In particular, they differ with regard to what it is that is considered Shinto’s core essence. In my dissertation, I have distinguished between six different paradigms, according to which Shinto has been conceptualised, defined and shaped in the course of modern history.

The first of these was dominant from the second half of the nineteenth century until the end of the Second World War, but it still lingers on. According to this view, Shinto is a national ritual cult focused on the worship of the divine ancestors of the imperial family; it was seen not as a religion defined by belief and personal membership, but as a collective Japanese, non-religious ritual tradition in which all citizens should take part. I have called this the ‘imperial paradigm’.

Back to nature. Shrines were a later invention after the spread of Buddhism. 'True Shinto' could be said to consist of outdoor worship.

After the Second World War, this imperial ritual and ideological system (which is often referred to as ‘State Shinto’) was dismantled; Shinto was subsequently established legally and politically as a religion. Accordingly, it was privatised, and it had to be redefined. According to the dominant post-war view, Shinto is the ancient, singular Way of ‘the’ Japanese people; it is an ethnic, racial faith, shared by all Japanese in the present and the past, by virtue of their nationality.

According to this view, Shinto encompasses the realm of religion, but it is much more than that: it is the essence of Japanese culture and mentality. As such, it is public and collective, not private or individual. Ono Sokyō, whom I quoted previously, is a representative of this paradigm. It has long been the view of many shrine priests. I call this the ‘ethnic paradigm’.

There are several alternative views, however. One of these is the ‘local paradigm’. It goes back to the work of the Japanese ethnologist Yanagita Kunio, who wrote most of his works before the war; in recent years, it seems to have acquired new popularity. Proponents of this paradigm challenge the focus on the imperial tradition, and of national unity, that characterises the other two.

According to them, the essence of Shinto cannot be found in powerful institutions; but, on the contrary, in local, rural worship traditions and beliefs, which have nearly disappeared. ‘Real Shinto’, according to them, can be found in the shamanistic and animistic traditions of the countryside – accordingly, they profess a nostalgic desire for a nearly-lost rural Japan, characterised by social harmony and harmony with nature.

Totoro, from the Miyazaki Hayao film – an exemplar of local folk Shinto? (courtesy fanpop.com)

This is the image of the popular film character Totoro, living in a grove near an old farmhouse, in a beautiful rural landscape (satoyama, as it is called in Japanese). In all these paradigms, Shinto is intimately connected with the land of Japan.

But there is an alternative paradigm, which has also been around since the pre-war period, and which I call the ‘universal paradigm’. According to this view, Shinto may have emerged in Japan, but it is essentially a salvation religion, which has the potential to reach out to – and maybe even save – the rest of the world. This view is characteristic of many membership-based groups, so-called new religious movements, which define themselves as Shinto. Yamakage Shinto is one of many examples.

There is some overlap with the fifth paradigm, which I call the ‘spiritual paradigm’. I think it is worth distinguishing between these two, as not all proponents of the spiritual paradigm have an international agenda; some are downright nationalist. Simply put, according to advocates of this view, Shinto is a religion without doctrine, a primordial worship tradition; it can only be truly grasped intuitively, by means of a mystical experience of the divine, not intellectually. Politics, theology, philosophy – it is all peripheral, according to this view.

Is Shinto a spiritual pursuit like Shugendo? Or is it rather a celebration of Japanese tradition?

Right-leaning activists around Yasukuni Shrine demanded the government embrace more nationalistic policies, such as revising the pacifist Constitution. They also called for recanting the so-called Kono Statement from 1993, which admitted the Japanese army and other authorities were at times involved in forcibly recruiting women, mostly from the Korean Peninsula, to provide sex to Japanese soldiers before and during World War II.

Right-leaning activists around Yasukuni Shrine demanded the government embrace more nationalistic policies, such as revising the pacifist Constitution. They also called for recanting the so-called Kono Statement from 1993, which admitted the Japanese army and other authorities were at times involved in forcibly recruiting women, mostly from the Korean Peninsula, to provide sex to Japanese soldiers before and during World War II.

Tree worship and tree motifs are frequently said to be a universal phenomenon, however, we would like to show that within the broad notion of the Sacred or Magical Tree, there are in fact distinctive categories and different concepts, and important distinctions and different characteristics will help identify the cultural sphere the object and mytheme belongs to, and the stage of evolution and complexity of the belief, practice or myth, will lend a perspective on the historical events and times associated with the myth and mytheme.

Tree worship and tree motifs are frequently said to be a universal phenomenon, however, we would like to show that within the broad notion of the Sacred or Magical Tree, there are in fact distinctive categories and different concepts, and important distinctions and different characteristics will help identify the cultural sphere the object and mytheme belongs to, and the stage of evolution and complexity of the belief, practice or myth, will lend a perspective on the historical events and times associated with the myth and mytheme.

Interestingly, the Scandinavians are now thought to have received influences from their Central Asian interactions with Scythian-Sarmatians, and with the Altai tribes: (see David K. Faux “The Genetic Link of the Viking – Era Norse to Central Asia: An Assessment of the Y Chromosome DNA”, Archaeological, Historical and Linguistic Evidence, 2004 – 2007)

Interestingly, the Scandinavians are now thought to have received influences from their Central Asian interactions with Scythian-Sarmatians, and with the Altai tribes: (see David K. Faux “The Genetic Link of the Viking – Era Norse to Central Asia: An Assessment of the Y Chromosome DNA”, Archaeological, Historical and Linguistic Evidence, 2004 – 2007)

The Kazakh epic Kobylandy mentions the world tree as a tree with golden leaves (in the epic it has the golden and silver leaves). In dastan of Kashagan, it is referred as a tree of all fruits. The Turkic people had widespread belief that people take the babies under the trees, or that the ancestors’ souls live in the branches and leaves. The branches of the shaman tree, according to the ideas of Turkic-Mongol people, host the souls, preparing for a new birth.

The Kazakh epic Kobylandy mentions the world tree as a tree with golden leaves (in the epic it has the golden and silver leaves). In dastan of Kashagan, it is referred as a tree of all fruits. The Turkic people had widespread belief that people take the babies under the trees, or that the ancestors’ souls live in the branches and leaves. The branches of the shaman tree, according to the ideas of Turkic-Mongol people, host the souls, preparing for a new birth.