From Wakkanai heading south, Asahikawa is the next significant outpost of civilisation. The train takes almost four hours, which gives an idea of the scale of Hokkaido. Asahikawa is not well-known, but is Hokkaido’s second biggest city with a population of 350,000.

********

At the Information Office, I looked for something special about Asahikawa. Guidebooks pitch it as the gateway to the Daisetsu mountain range, which is Hokkaido’s no.1 tourist destination. ‘Do you have something on mountains, perhaps?’ I asked, and sure enough a glossy brochure was produced – ’Coexisting with the Kamuy: The Kamikawa Ainu’ (Kamuy is the Ainu name for spirits, Kamikawa a sacred river). Inside was a map of Ainu villages and an area labelled ‘Playground of the gods’. Perfect.

The brochure spoke of ‘magnificent waterfalls’, ‘mysteriously-shaped rocks’ and ‘enigmatic lakes’. There were religious sites too, such as a riverside rock from which shaved sticks called Inau were offered to the river god for safe passage through the rapids. One caption spoke of ‘Gorges filled with snow which has not melted in ten thousand years.’ I needed a moment or two to take in the time scale. Seeing that, touching it, savouring it – now that would be special!

*********************

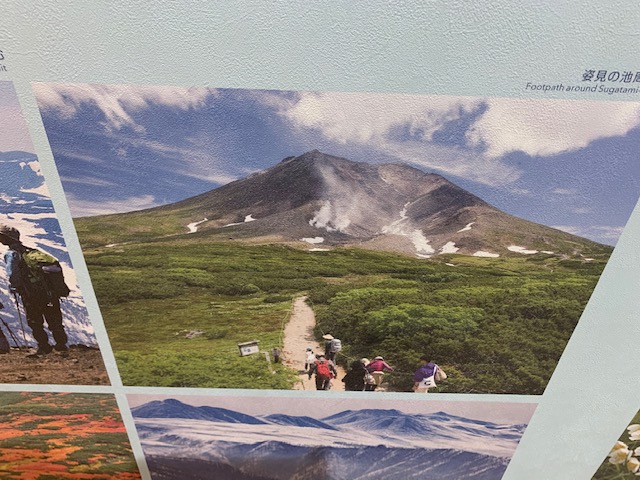

Hokkaido was once two separate islands, which merged into each other as the tectonic plates beneath them collided. The movement forced up the Daisetsu range, which the Ainu named, descriptively, ‘Vast Roof Covering Middle Hokkaido.’ The tallest of the mountains, the highest in Hokkaido, is Mt Asahidake (2291m, 7513 ft), and the Visitors Center at its base has a list of adventurous activities, which along with hiking and river rafting include snowshoeing, air boarding, dog-sledding, and even ‘treeing’.

The route to the top is six kms (3.7m), which there and back takes eight to nine hours to complete. The volcano is still active, so there is no shortage of hot springs available afterwards to soak weary limbs. Skiing is particularly popular, because, according to the Visitors Center, the mountain has ‘the best powder snow in the world’. Really?

Near the Visitors Center a ropeway runs up to 1600m (5200 ft), transporting passengers literally and figuratively to a different realm. In ancient times mountains with a special sense of presence were considered sacred, and Asahidake was sacred to the Ainu. The ride is spectacular – the rarefied atmosphere, the soaring heights, the magnificence of nature. With its waterfalls, pristine lakes and alpine flowers you can see why the Ainu would have thought it a paradise on earth.

At the top a one-hour walk leads to a volcanic landscape with crater lakes. It is the first place every year to display autumn colours in Japan, and the crowning glory is the sight of bright red maple leaves against thick white snow. How divine is that! In winter there are pillars of light and sparkling ice crystals known as ‘diamond dust’, while in spring streams burst into life with the melting of the snow, surging down to the valley below. As in India, the fresh mountain water was seen as a living entity, gifted from the gods on high. Amongst the animal life here are brown bears and – new to me – a furry relative of the rabbit called pika which burrows underground. Cute!

Within this paradise were swarms of dragonflies, darting back and forth in delight at the sunshine. It reminded me of Emperor Jomei, who as early as the seventh century had written of ‘My Yamato, Island of Dragonflies’. It was only when I got back to the wifi comfort of my hotel that I discovered there are a staggering 5000 varieties worldwide, of which 200 exist in Japan alone. Dragon is a powerful moniker for such a fragile creature, yet it captures the appeal of the brightly coloured creatures, for in their flight and love of water they evoke the vision of transitioning between realms. Perhaps the Pure Land priest, Issa, had something similar in mind when he wrote…

dragonfly –

distant mountains

reflected in its eyes

Another writer with an affinity for insects was Lafcadio Hearn, whose interest resulted in a remarkable twenty essays of detailed observation. His eyesight was abysmal, but his one-eyed myopia led him to focus on close-ups through a magnifying glass. He particularly appreciated the value given to insect song in Japanese culture, for ’the music of insects and all that it signifies in the great poem of nature tells very plainly of goodness of heart, aesthetic sensibility, a perfectly healthy state of mind.’