I have long been intrigued by the gender of Amaterasu because I grew up believing it was a matter of common sense that the sun was male and the earth female. The hot and active sun sends out rays, which like fructifying sperm fertilise the female into producing offspring. Hence the epithet Mother Earth and her depiction as a pregnant Earth Mother.

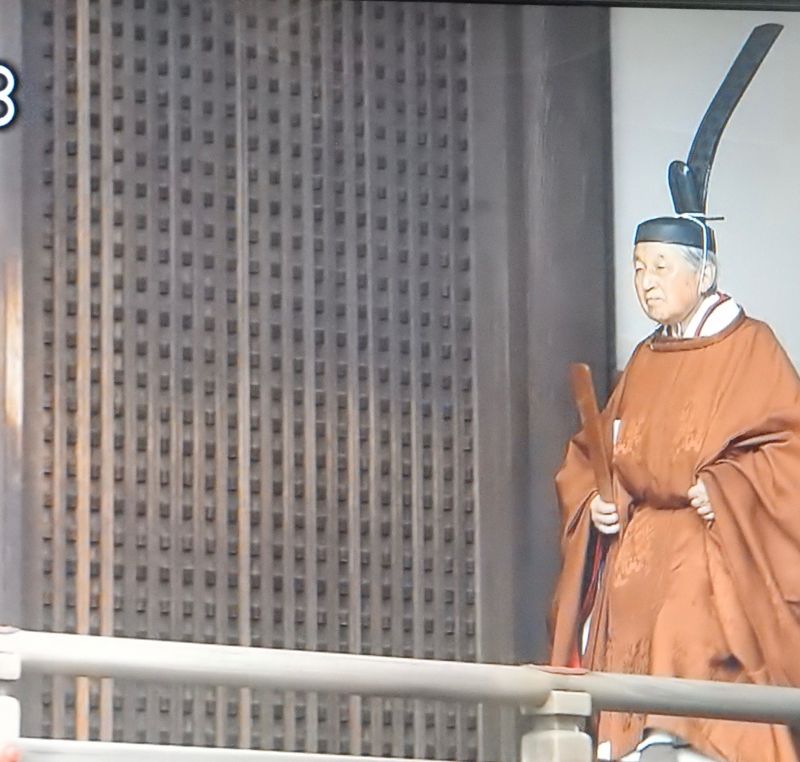

It was a surprise therefore to find that the sun in Japan was female and ancestress to the emperor. This went along with a male moon, which was even odder for if anything seems to embody yin and feminine attributes you would imagine it to be the moon.

From my readings I learnt that the sun as female was by no means unique to Japan. I also learnt from Mark Teeuwen in a talk to Writers in Kyoto that Amaterasu might well have started as male. Here is what I wrote in a previous posting:

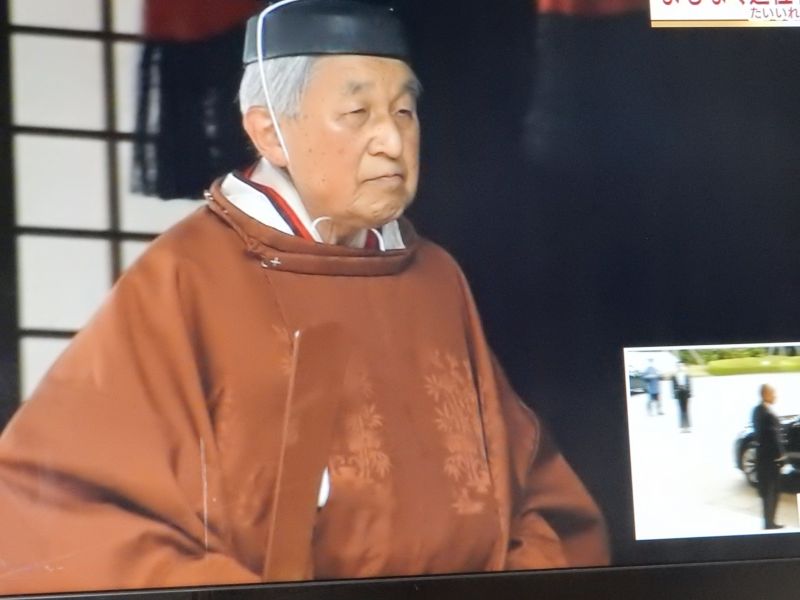

“The shrine dates back to the late seventh century when an angry deity named Amateru (sic) disrupted the imperial household and was ejected, ending up at Ise. Mark T. believes that at this time the deity was male, and that it was only under the influence of Empress Jito (r.686-697) that the deity was feminised by Kojiki mythologisers in her honour (there are parallels between Amaterasu’s son and grandson with those of Jito).”

Now I have chanced upon a new angle on the matter, which comes from the Encyclopedia of Korean Folk Culture. Much of early Shinto came to Japan through Korea, and probably the whole Yamato imperial line, so it is interesting to see in this folk tale some gender shifting. Here follows an excerpt from the encyclopedia, topical because this is the year of the tiger!

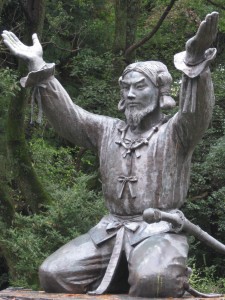

A tiger ate up an old mother returning home after providing labor at a rich household, and after disguising himself with the mother’s clothes and headwrap, went to the home where the mother’s son and daughter were waiting and asked them to open the door. The brother and sister peeked out and realizing that it was a tiger, they ran out through the back door and climbed up a tree. The tiger climbed the tree after them and the brother and sister prayed to the heavens, upon which a metal chain was sent down for them and they climbed up to become the sun and the moon. The tiger tried to come after them on a crumbling straw rope, which broke and the tiger fell on a sorghum field and died. The heavens first assigned the brother as the sun and the sister as the moon, but the sister was afraid of the dark and their roles were switched. The sister, shy of all the people looking up during the day, illuminates with intense light.

Of particular interest are the variations of the tale (see here). The commentary notes that, ‘The variations seem to have been based on the instinct to adhere to the conventional association of the male with the yang energy and the sun.’ Interesting to see the ancients had the same reservations as myself!

I had a Japanese colleague once, a very bright lady, who simply assumed Amaterasu was male and was surprised to hear that she was worshipped as a female. As we move into an era of ‘fluid gender’ and debates about trans- and cis-, perhaps it is altogether appropriate for our time that Amaterasu be ascribed a role in both /all genders. Much like Inari, indeed!

Thanks to Jonathan Swire, we also have input from Basil Hall Chamberlain’s collection of Ainu folk tales, which features a prudish Sun Goddess and a different kind of crossover, from night to day

Formerly it was the female luminary that came out at night. But she was so greatly shocked at the immoralities which she saw going on out of doors among the grass, that she exchanged with the male luminary, who, being a man, did not care so much. So now the sun is a female deity, and the moon is a male deity. But surely the sun must be often shocked at what she sees going on even in the day-time, when the young people are in the open among the grass.—(Written down from memory. Told by Ishanashte, November, 1886.)