Izanagi and Izanami stirring the primordial liquid to create Japan. In one version of the myth, Izanami dies and her corpse decays, in another version she mothers Amaterasu and her two brothers.

Last Monday David Lurie of Columbia University gave a talk in Kyoto about ‘Dead Goddesses and Living Narratives’. It centred around the differences between the Kojiki (712) and Nihon Shoki (720). As is well-known, the two books cover similar myths but in different ways. The Kojiki is more of a straightforward official narrative, whereas the Nihon Shoki attempts to be more historical by providing alternative versions of the same story. These variants are only given for the first two books of the Nihon Shoki dealing with the Age of the Gods, following which the narrative takes a more historical tone with annal-style dates and records.

One important point the speaker pointed out is that the myths were written in a Buddhist age about a pre-Buddhist past. One needs therefore to view them through that prism. In the Kojiki, the narrative is strung together by genealogy, and the structure is broken into three different parts. The first deals with Japan’s creation, the birth of gods, the struggle with Earthly deities who finally yield, and the descent of Ninigi no mikoto (an event known as tenson korin). The second part deals with the exploits of legendary Emperor Jimmu, Japan’s first human emperor, and the third part with his successors.

Susanoo slaying the eight-headed serpent

The Kojiki narrative is in places at variance with the Nihon Shoki, which is odd considering they were both apparently court sanctioned. The death of Izanami provides an example. In the Kojiki the decay of her corpse gives rise to all kinds of new deities and creativity. In the Nihon Shoki there is no such death (and there is no afterworld, or yomi, either). Moreover, in the former Amaterasu and her two brothers, Tsukuyomi and Susanoo no mikoto are born by pathogenesis from Izanagi’s eyes and nose after he does misogi. In the latter they are born through straightforward copulation, since Izanami has not died. In this respect you could say the Kojiki version is magical, the Nihon Shoki more rational.

Another big difference comes in the Izumo cycle, where in Kojiki Susanoo slays Ogetsuhime (Lady Great Sustenance) when he realises that she has made food for him from her bodily cavities, including from her rear. It’s a mythic story that not only explains the origin of foodstuff through the cycle of decay and rebirth but the beginnings of silkworm, which emanate from her head after she dies. (The higher the cultural value, the higher the part of the body from which it emerges.)

In Nihon Shoki there is instead Ukemochi (Food Provider) who is killed by Tsukuyomi, the moon god. This enrages Amaterasu, who exiles him to nighttime and darkness. In this story the silkworm derive from Ukemochi’s eyebrows, following which Amaterasu fosters them in her mouth and initiates the practice of sericulture, which was an important part of Japanese culture right into modern times (silk was the number one export of Meiji Japan).

How does one explain these discrepancies? The standard line is that Kojiki was written as a narrative myth to legitimate the ruling family, while Nihon Shoki was more of a Chinese-style history for official purposes. In other words, the former was a private family affair, the latter a public national record. David Lurie suggested too that in contrast to Nihon Shoki with its team of workers, the Kojiki may have been a private project of O no Yasunoro, who only won official recognition after its completion. Since it was written before Nihon Shoki, the court historians made use of it in their own compilation, and it is usually included as one of the several variants for each story (usually variant no. 6).

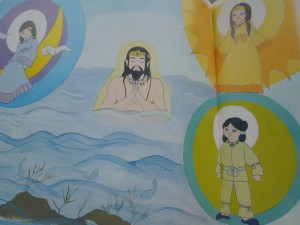

Izanagi undergoes the primal misogi which led to the birth of Amaterasu, Susanoo and Tsukuyomi in the Kojiki version of the myth

One postscript from this. I’ve long been puzzled by the relative absence of the moon god Tsukuyomi from Japan’s shrine deities. Given the significance of the moon in Japanese culture, one might imagine he would play an important balancing role to the sun goddess. One theory I’ve come across to explain his obscurity is that he may have been the deity of a rival clan to the Yamato, and was therefore suppressed. However, David Lurie mentioned two other interesting possibilities. One was that Susanoo was in fact originally the moon god but was later split off as a separate character. The other was that the moon-god was simply an invention for yin-yang purposes and that he was inserted into the text to take over part of Susanoo’s role.

All in all, one came away from the evening thinking there is more to myth than one might think. Those clever historians of the late seventh and early eighth centuries had great talent and vivid imaginations!