This is an extract from a forthcoming book about travel by train the length of Japan. (For Part One click here.)The passage considers the historical treatment of animals in Japan. Despite being a so-called nature religion, Shinto has shown a greater concern for nationalist issues than animal rights, and it is Buddhism that has played the leading role in concern for our fellow creatures.

************************

Next morning I headed for Hakodate’s morning market. The Covid effect was much in evidence in the empty stalls, yet row upon row of fresh fish was laid out in neat display as if through force of habit. Some of the workers were up to their elbows in guts and gills, while others were out hustling passers-by. Set on its own in the middle of the market, like a prime showpiece, was a gigantic crab singled out for its size and feebly moving its legs against a narrow glass tank. A wave of crustacean compassion washed over me.

It was lunchtime, so I let myself be hustled into a surprisingly spacious dining room in which sat a single Japanese couple. What was it like pre-Covid, I asked the waitress. ‘A full house,’ she answered. How many would that be? ’Eighty,’ she said, ‘They come in large groups.’ I presumed that was in summer, ’No, they come all year round. Mainly tour groups for pensioners.’

The market is known for squid, so I ordered a set meal and waited. Tanks of the creatures lined one of the walls, and there were notices warning against sprayed ink. Restaurant staff in happi and headband stood around with nothing much to do, and I was scribbling down a few notes when out of the corner of an eye I noticed something moving next to me. Turning to look, I found myself staring straight into the face of a living creature with eerily undulating tentacles. I thought it must be moving post-mortem, like a headless chicken, but the continued wriggling indicated it was very much alive. ‘Sumimasen,’ I yelled out, ‘Please take this away.’ ‘But you ordered it,’ responded the puzzled waitress.

Realising I was adamant, she took the plate off to the kitchen, returning minutes later with neatly cut strips of fresh squid. I looked at the plate, then at her. ‘Is that the same one you brought before?’ I asked, and hearing it was, I hesitated. Somehow in our eye-to-eye encounter I felt that we had bonded. Was I really going to eat it? For a moment I wavered on the point of refusing, but then I thought of the Ainu who would see it as a divine gift from the Great Squid Spirit, and I thought of Buddha who said not to refuse what had been served by another. But most of all, I thought of the kitchen staff staring at me. There was no way I was going to confirm their prejudice about weak-willed gaijin unable to stomach Japanese food. And so, dear reader, I ate it.

Afterwards I had some questions for the waitress.

‘Is it usual to serve the squid while it’s still alive?’

‘Yes’, she said, ‘Japanese customers like it.’

‘They like it! Why?’

‘Maybe they want to know it’s fresh. And if they watch it dying they know it is fresh.’

‘You mean they like to watch the squid die?’

‘Yes. Maybe it will change colour,’ she said matter-of-factly.

‘Then what happens?’

‘Then it’s sliced and served.’

At this point I plead guilty to hypocrisy. I happily chew dried squid with a glass of saké, but I am squeamish about seeing one dying. Humans are emotional by nature, and little of what we do makes rational sense, though we like to think it does. We pamper certain animals, and torture others. The French eat horse meat, the Koreans dog meat, the Japanese serve live squid. We defend practices that suit us and oppose those that are alien. It is all cultural, for sure. But still… watching your food die on your plate?

The treatment of animals in Japan throws up some interesting historical quirks. In 675 Emperor Tenmu issued a ban on meat eating, particularly domestic animals, though seafood was allowed because reincarnation was thought to be restricted to land animals. (I presume that is where Shinto’s preferennce for offerings of sea food rather than meat originates.)

Venison and wild boar had previously been popular, but as time passed the ban was applied to all four-legged animals – except hares (rabbits), which were counted as birds. Many people think this is because of their large ears which flap like wings, but in fact it is due to a linguistic oddity because in Japanese the verb tobu, which means jump and fly, is applied to both hares and birds.

The haiku master, Kobayashi Issa (1763-1824), was a Pure Land priest with a great compassion for animals, including insects. Such was his depth of feeling that he would hold out his arm for hungry mosquitoes. In the haiku below he shows pity for a stranded insect, identifying perhaps with its poetical ‘chirping’ in a ‘floating world’.

Still chirping

the insect is carried away –

floating branch

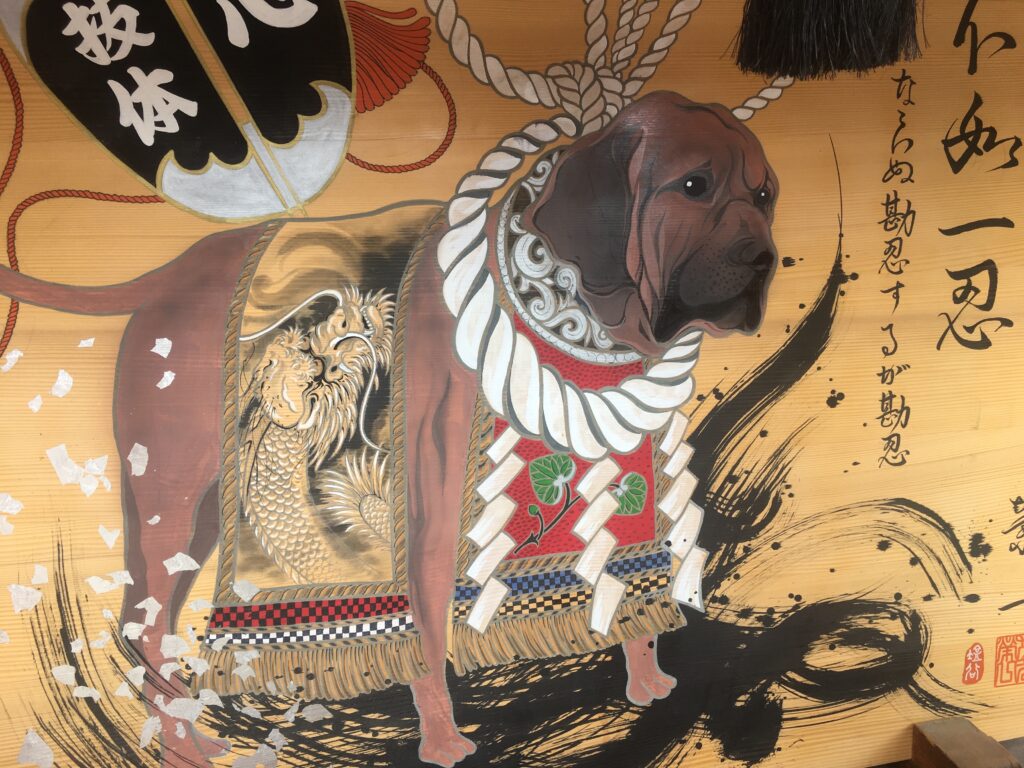

When it comes to animal rights, not even Issa can compare with the ‘dog shogun’, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. In a remarkable series of laws from 1687-1709, he issued Orders on Compassion for Living Things which stipulated that those who abused animals should be punished. The strictures were progressive, even by today’s ‘enlightened’ standards. A weight limit was set for working horses, and the caging of singing insects was banned. Punishments were severe: a public officer was exiled to a remote island for having thrown a stone at a dove.

Tsunayoshi was born in the Year of the Dog, hence the preferential treatment for the animal. If any dog was injured, the owner was held responsible and punished. It led to the mass abandonment of pets, and kennels had to be built to cope with the strays. The number of dogs in care is estimated to have ranged between 100,000 and 200,000, all of which had to be fed. It was big business, and for each dog the kennels received the equivalent of a man’s salary. Such was the cost that it depleted government coffers, surely the only example in human history of dogs nearly bankrupting an economy.