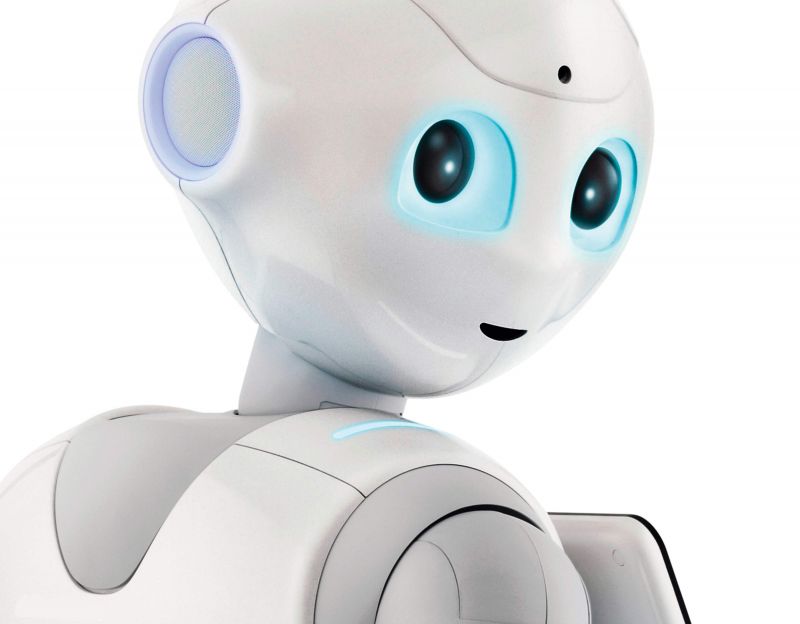

Robot friends are on their way to a shop near you

An article by Joi Ito on wired.com brings up the topic of why Japanese appear to be more disposed to seeing robots in a positive manner than Westerners. It’s a subject Green Shinto has covered before, notably when Christal Whelan wrote from the viewpoint of mana (see here).

Like many others, Joi Ito calls for a rethinking of our attitudes, away from the human-centric thinking that sees the rest of the world, whether living or not, as simply something that is there for our exploitation. What we need is a Gaia-centric outlook.

Ancient religions taught that we are an integral part of the world around us. It’s something that Alan Watts always stressed. And it’s something that struck me the other day when listening to a Native American speaking of rocks as ‘our brothers and sisters’. What a leap in consciousness from our economic imperative which drives the brutal rape of the earth. Too bad for us. The earth will survive, but whether humans will is looking increasingly doubtful.

****************

Why Westerners Fear Robots and the Japanese Do Not

by Ito Joi (July 30, 2018, Wired)

AS A JAPANESE, I grew up watching anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion, which depicts a future in which machines and humans merge into cyborg ecstasy. Such programs caused many of us kids to become giddy with dreams of becoming bionic superheroes. Robots have always been part of the Japanese psyche—our hero, Astro Boy, was officially entered into the legal registry as a resident of the city of Niiza, just north of Tokyo, which, as any non-Japanese can tell you, is no easy feat. Not only do we Japanese have no fear of our new robot overlords, we’re kind of looking forward to them.

It’s not that Westerners haven’t had their fair share of friendly robots like R2-D2 and Rosie, the Jetsons’ robot maid. But compared to the Japanese, the Western world is warier of robots. I think the difference has something to do with our different religious contexts, as well as historical differences with respect to industrial-scale slavery.The Western concept of “humanity” is limited, and I think it’s time to seriously question whether we have the right to exploit the environment, animals, tools, or robots simply because we’re human and they are not.

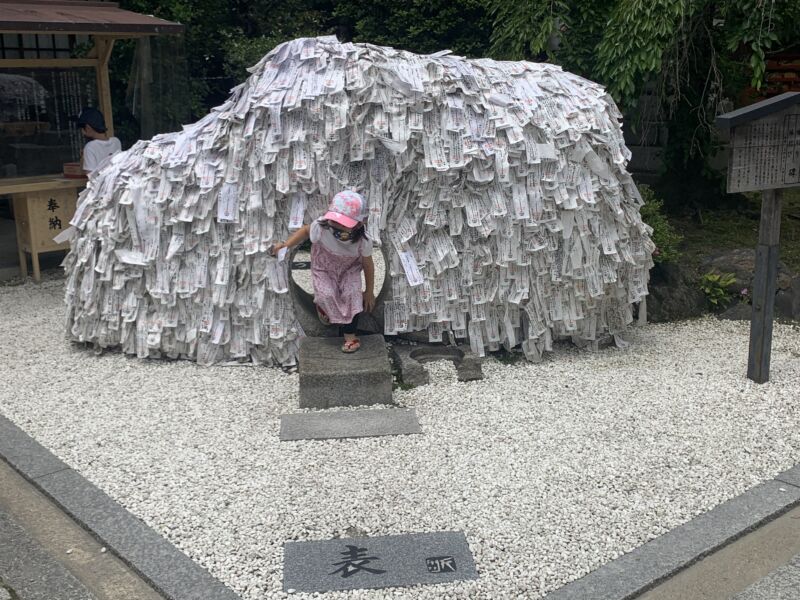

Dolls are important in Japanese culture, and there are services for used dolls that have given years of service

SOMETIME IN THE late 1980s, I participated in a meeting organized by the Honda Foundation in which a Japanese professor—I can’t remember his name—made the case that the Japanese had more success integrating robots into society because of their country’s indigenous Shinto religion, which remains the official national religion of Japan. Followers of Shinto, unlike Judeo-Christian monotheists and the Greeks before them, do not believe that humans are particularly “special.” Instead, there are spirits in everything, rather like the Force in Star Wars. Nature doesn’t belong to us, we belong to Nature, and spirits live in everything, including rocks, tools, homes, and even empty spaces.

The West, the professor contended, has a problem with the idea of things having spirits and feels that anthropomorphism, the attribution of human-like attributes to things or animals, is childish, primitive, or even bad. He argued that the Luddites who smashed the automated looms that were eliminating their jobs in the 19th century were an example of that, and for contrast he showed an image of a Japanese robot in a factory wearing a cap, having a name and being treated like a colleague rather than a creepy enemy.

The general idea that Japanese accept robots far more easily than Westerners is fairly common these days. Osamu Tezuka, the Japanese cartoonist and the creator of Atom Boy noted the relationship between Buddhism and robots, saying, ”Japanese don’t make a distinction between man, the superior creature, and the world about him. Everything is fused together, and we accept robots easily along with the wide world about us, the insects, the rocks—it’s all one. We have none of the doubting attitude toward robots, as pseudohumans, that you find in the West. So here you find no resistance, simply quiet acceptance.” And while the Japanese did of course become agrarian and then industrial, Shinto and Buddhist influences have caused Japan to retain many of the rituals and sensibilities of a more pre-humanist period.

Protective amulets on sale at a shrine on the Fushimi Inari hill

In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari, an Israeli historian, describes the notion of “humanity” as something that evolved in our belief system as we morphed from hunter-gatherers to shepherds to farmers to capitalists. As early hunter-gatherers, nature did not belong to us—we were simply part of nature—and many indigenous people today still live with belief systems that reflect this point of view. Native Americans listen to and talk to the wind. Indigenous hunters often use elaborate rituals to communicate with their prey and the predators in the forest. Many hunter-gatherer cultures, for example, are deeply connected to the land but have no tradition of land ownership, which has been a source of misunderstandings and clashes with Western colonists that continues even today.

It wasn’t until humans began engaging in animal husbandry and farming that we began to have the notion that we own and have dominion over other things, over nature. The notion that anything—a rock, a sheep, a dog, a car, or a person—can belong to a human being or a corporation is a relatively new idea. In many ways, it’s at the core of an idea of “humanity” that makes humans a special protected class and, in the process, dehumanizes and oppresses anything that’s not human, living or non-living. Dehumanization and the notion of ownership and economics gave birth to slavery at scale.

*****

Lots of powerful people (in other words, mostly white men) in the West are publicly expressing their fears about the potential power of robots to rule humans, driving the public narrative. Yet many of the same people wringing their hands are also racing to build robots powerful enough to do that—and, of course, underwriting research to try to keep control of the machines they’re inventing, although this time it doesn’t involved Christianizing robots … yet.

*****

My view is that merely replacing oppressed humans with oppressed machines will not fix the fundamentally dysfunctional order that has evolved over centuries. As a Shintoist, I’m obviously biased, but I think that taking a look at “primitive” belief systems might be a good place to start. Thinking about the development and evolution of machine-based intelligence as an integrated “Extended Intelligence” rather than artificial intelligence that threatens humanity will also help.

As we make rules for robots and their rights, we will likely need to make policy before we know what their societal impact will be. Just as the Golden Rule teaches us to treat others the way we would like to be treated, abusing and “dehumanizing” robots prepares children and structures society to continue reinforcing the hierarchical class system that has been in place since the beginning of civilization.

It’s easy to see how the shepherds and farmers of yore could easily come up with the idea that humans were special, but I think AI and robots may help us begin to imagine that perhaps humans are just one instance of consciousness and that “humanity” is a bit overrated. Rather than just being human-centric, we must develop a respect for, and emotional and spiritual dialogue with, all things.

******************

For a related Green Shinto article which focusses on the Japanese use of dolls, please click here.

Jun Ito has been recognized for his work as an activist, entrepreneur, venture capitalist and advocate of emergent democracy, privacy and internet freedom. He is coauthor with Jeff Howe of Whiplash: How to Survive Our Faster Future. As director of the MIT Media Lab and a professor of the practice of media arts and sciences, he is currently exploring how radical new approaches to science and technology can transform society in substantial and positive ways.