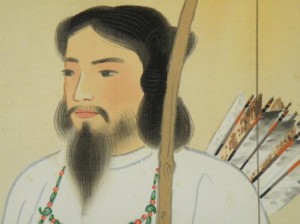

Ino Okifu

It was after speculating about Jofuku and Jimmu that I was startled to find, courtesy of Wikipedia, that I was by no means the first to think that their stories may have overlapped. It turns out that a scholar named Ino Okifu had come to a similar conclusion, though the Wikipedia page goes on to say that his theory of Jimmu being based on Xu Fu (Jofuku) has been rebutted.

It seems Ino Okifu was a Waseda University student, who spent much of his life abroad and as a historian was concerned about the atrocities committed by the Japanese in WW2. It fuelled a desire to disprove the notion of divinity surrounding the imperial line. His theory presumed that Xu Fu was a powerful figure with medical expertise, who fell out with Emperor Qin and was sent on a fool’s errand in quest of mythical Panglai (an island paradise known as Horai in Japan). Fearing that he would be executed on his return, Xu Fu chose to settle in Japan instead, and amongst the advanced knowledge that he introduced were elements of Taoism, which shaped the formation of early Shinto.

If Ino Okifu had a vested interest in presenting his theory, then so did his detractors in refuting it. They included conservatives who wished to maintain the notion of Japanese uniqueness, as well as nationalists eager to preserve the mystery surrounding the emperor’s origins. (Even today imperial graves remain off-limits to archaeologists.)

While it is clear there were close ties between Kyushu and Korea in ancient times, it is less clear how much direct influence China had on Japan, particularly in the development of rice culture. The Kokugakuin Encyclopedia of Shinto gives an indication of the complexity…

It is not clear to what extent immigrants from China contributed to the development of rice cultivation culture, or even before that whether that foundation we could call the East Asian cultural sphere had extended as far as Japan. However, as concerns customs related to rice cultivation, it can be assumed that was a certain degree of commonality from the start throughout East Asia in general. Rather than saying that agricultural rituals or ancestor veneration practices (sosen sūhai) related to cultivation were influenced by imported cultural elements, it is better to think of them as a common denominator throughout the East Asian cultural sphere. It is extremely difficult to discuss questions of influence in the earliest periods.

(courtesy Australian National University)

Cross currents

Given the above, the situation is evidently unclear. Nonetheless there are links with China which give pause for thought. DNA testing of Japanese rice from 2200 years ago, just when Xu Fu came to Japan, show the origin to be China’s Yangtze Delta (see here). It should be noted too that rice arrived in Miyazaki relatively early compared to the rest of Japan.

Yayoi skeletons from the BC period in Kyushu resemble those of China’s Jiangsu Province and differ from the Kumaso of south-east Kyushu and the Korean type of northern Kyushu. Though Japanese language origins are a controversial area, linguists such as Christopher Beckwith (2004) maintain that the ‘the original homeland of the speakers of the Japanese-Koguryo language may have been close to South China.’

It is widely acknowledged that the rituals of purification and cleansing with which Shinto is concerned originated in Taoism. What’s more, such aspects as turtle shell divination, which involved roasting and ‘reading’ the cracks, was an imported court custom, and the Qin emperors had a jade royal seal to go along with their bronze mirrors and swords as a show of authority. (Japan’s regalia, along with a mirror and sword, includes a magatama jewel made of jade, which in China signified inner beauty and immortality.)

Much of Japanese mythology, such as the weaving princess, shows clear links with southern Chinese agricultural myths, and Chinese historical records mention expeditions to Japan. Folk memory too suggested ties, and as late as the 16th century the missionary scholar Joao Rodriques in This Island of Japon claimed that Hyuga (modern Miyazaki) was the first part of Japan to be settled, notably by people from Fukien and Chekiang Provinces (modern Fujian and Zhejiang). ‘The people were cast up there by a storm, as still happens even now,’ he wrote, bringing the Kuroshio current to mind once again.

Mythology by its very nature is what you make of it, and the intermingling of early Chinese, Korean and Japanese cultures cannot be easily unpicked. Even the very identity of the Yayoi people is uncertain. Let us end then with a quotation from Wikipedia, which states with references that, “The most popular theory is that they [the Yayoi] were the people who brought wet rice cultivation to Japan from the Korean peninsula and Jiangnan near the Yangtze River Delta in ancient China. This is supported by archeological researches and bones found in modern southeastern China.”

So was Jofuku a prototype for Jimmu? It seems not implausible that some folk memory of him was interwoven with later myths of invading forces. Perhaps it’s not so far-fetched as it might at first seem. After all, how else would one explain divine descent onto Mt Takachiho?

*******************

For Part One of this series click here, and for Part Two here.