The following is adapted from a Japan Times article, which can be accessed here, written by Alex K.T. Martin and dated March 20, 2021. It shows how the crisis is hitting the revenue of both shrines and temples, and the need for new ways of raising revenue.

****************

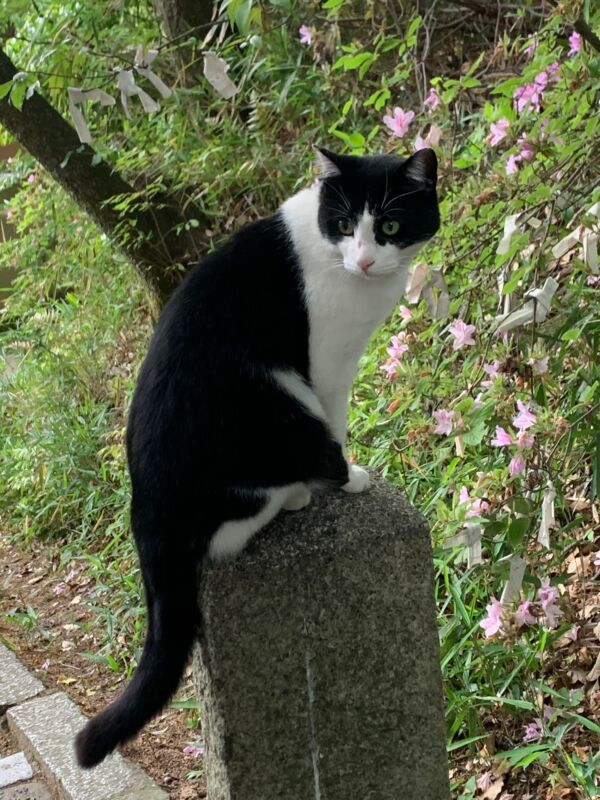

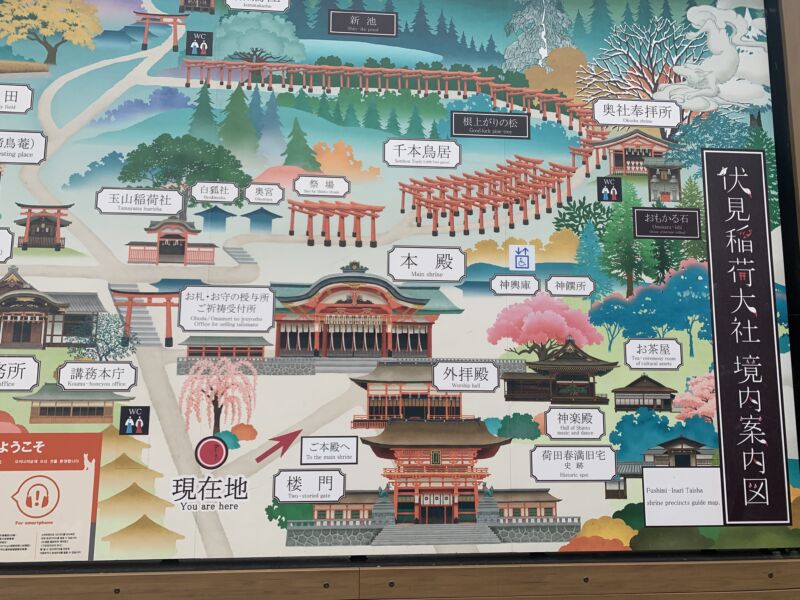

In Japan, where there are more temples and shrines than convenience stores, the Covid situation is financially straining Buddhist and Shinto institutions that rely on donations from parishioners. Already burdened by a shrinking and aging population, the pandemic has prompted a reckoning among monks and priests about how to survive in a future where mass infections are a real threat.

“The virus is having a major impact on religious institutions in Japan, with ceremonies being curtailed and funeral rituals being simplified,” says Hidenori Ukai, a journalist and chief priest at Shogakuji temple in Kyoto. Ukai estimates that total revenue for Japan’s temples fell to around ¥270 billion in 2020 compared to ¥530 billion in 2015. If the pandemic continues, he says, the figure could decline further to ¥230 billion this year.

“At the same time, religion offers solace during uncertain times. Once the situation stabilizes, I think we will see worshippers return en masse,” he says. “In the meanwhile, there are new, unique initiatives being rolled out that are changing the way people worship.”

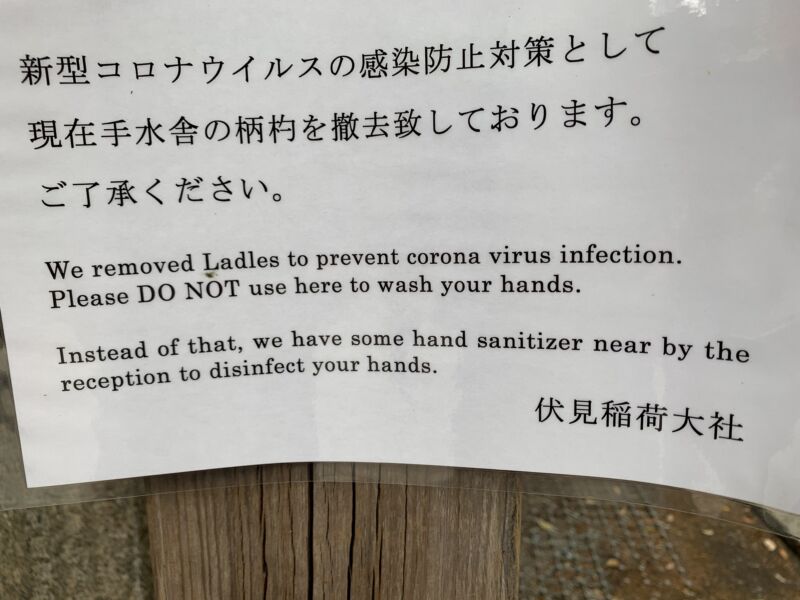

The slump in tourism and the rise of stay-at-home requests have also hit the coffers of the nation’s approximately 81,000 Shinto shrines that primarily rely on cash offering from visitors and ceremonial fees as sources of income. It has also prompted worshippers to seek out alternative means to pay their respect to institutions.

At Kashima Shrine in Kashima, Ibaraki Prefecture, priests have revived an ancient tradition for the first time in 90 years after parishioners asked the shrine to devise a way for them to offer prayers remotely.

Starting this year, a representative known as an oshi has been chosen to visit the shrine on the first of every month to pray on behalf of worshippers.

“The ritual is recorded on video and uploaded to a streaming platform for participants to watch,” says Tomonori Niikura, a spokesperson for the shrine. Those wishing to take part in the service can submit an application with monetary offerings starting at ¥7,000.

Tadashi Matsunobu, a director of the local tourism association whose ancestors were oshi, was selected to assume the role.

“My grandfather used to be an oshi until the early Showa Era (1926-89), when the practice disappeared,” he says. Oshi were essentially missionaries for the shrine that traveled to spread faith and deliver ofuda paper talismans to households.

“I gladly accepted the offer and have been trying my best to convey the wishes of parishioners to the gods,” he says.

With communal gatherings frowned upon, many shrines and temples have been devising ways to appeal to worshippers spending more time at their homes.

Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, for example, accepts online applications for prayers and sells protective amulets and other goods — including face masks and even confectionery — on its website. Enzoji temple in Saitama began airing YouTube clips of comic rakugo raconteur performances and yoga lessons filmed at the temple.

Yumiko Waguri, the chief editor of “Wagense,” a Buddhist quarterly magazine, says the pandemic has seen temples and shrines finding new ways to meet the spiritual and emotional needs of people in the confines of their dwellings.

Her magazine has been featuring stories on how to appreciate Buddhist teachings at home while incorporating some of its practices in daily routines.“Sales of our magazine grew since we focused on the concept of ouchi (home),” she says.

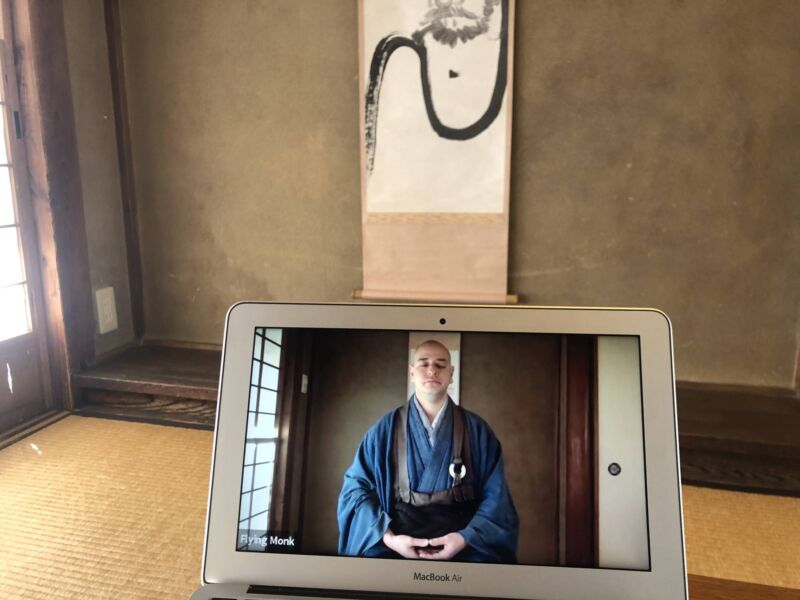

An organization called Terakoya Buddha, for example, hosts online Zoom meetings everyday at 7 a.m. in which monks lead viewers through a 20-minute session involving meditation and mindfulness.

“Those who want to discuss specific issues can chat with the priests to seek advice,” Waguri says.

Meanwhile, temples in graying, rural communities are trying to help older, digitally unsure parishioners who are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, she says.

“I know a temple in Shimane Prefecture that lends tablets to older households and offers to set them up so that people can join online services to avoid crowds,” she says.

And while technological innovations are bridging the social distance in an era of self-isolation, Waguri says traditional rituals associated with death are also being forced to change.