Zen or Shinto? The gardens and aesthetics are similar..

It’s often said that while Shinto is concerned with affairs of this world, Buddhism looks to salvation in the next. Hence the emphasis in Shinto on rites of passage, such as birth, 7-5-3, weddings, yakudoshi ages of transition, etc. Buddhism by contrast is concerned with death, so much so that the term ‘funeral Buddhism’ is widespread and temples are said to derive their income largely from services for the departed. In this way Shinto and Buddhism complement each other.

However, I came across this passage recently, which made me rethink the relationship, at least in terms of Zen. It suggests a surprising commonality of worldview.

Zen tries to help man live fully in this world. This is called the expression of full function. Zen stresses present rather than future, this place rather than heaven. It aims at making actuality the Pure Land.

Religion, of course, transcends the world of science, but it should not conflict with science. Buddhism is a world religion that envelops science. Any religion that hopes to appeal to modern man must embrace science and as well as transcend it. Zen does this.

In conclusion, Zen….

* Frees man from enslavement to machines and reestablishes his humanity;

* Eases mental tension and bring peace of mind; and

* Enables man to use his full potentialities in daily life.From this grow the Zen characteristics of simplicity, profundity, creativity, and vitality that have attracted so many Westerners. (S. Hisamatsu in ‘Zen and Art’ p.24, states that the 7 characteristics of Zen art are asymmetry, simplicity, austerity, naturalness, profundity, detachment, and tranquility.)

If Zen is truly concerned with this world, then what are we to say about the differences? Particularly since the characteristics overlap so closely with Shinto – simplicity, austerity, naturalness, asymmetry…

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.

In this respect one has to wonder if Zen is not a more sophisticated view of the notion that humans are the children of kami. In other words, we all have ‘kami nature’ which is pure in spirit, just as in Zen we all have buddha-nature. It’s why we need the ‘magic cleansing’ of the oharai from time to time, to clean us of the dust of this world. No wonder that both Shinto and Buddhism use mirrors on their altars.

There are however two striking differences that come to mind. One has to do with individualism. Zen aims for personal salvation; Shinto looks to the well-being of the group (family, community, nation). The other striking difference is in perspective. Zen seeks truth within, whereas Shinto looks for harmony on the outside. In other words, Zen is inward looking and Shinto outward.

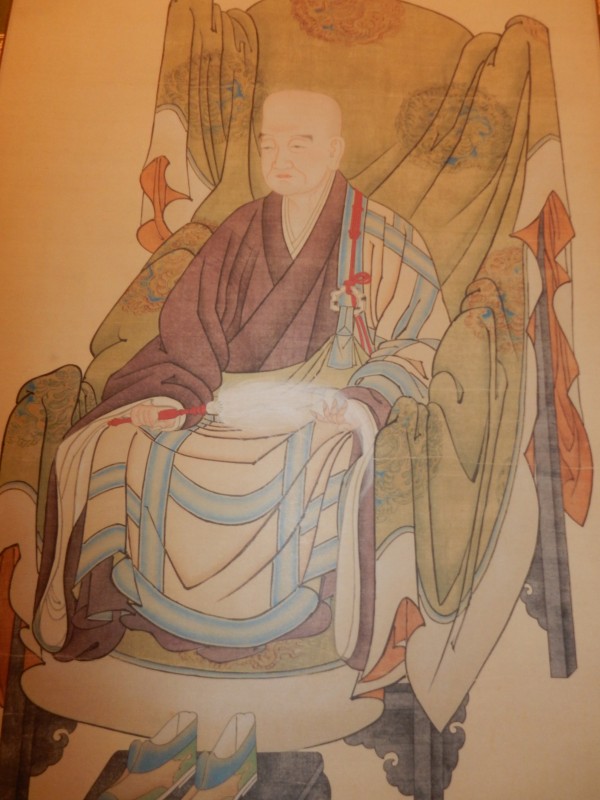

Zen’s search for inner truth centres around the meditation hall (zendo)

The fundamental concern of Zen is to uncover one’s true self, the self that lies beneath the rational thinking ego. It’s the self that functions unconsciously, breathing and digesting and making a myriad ‘decisions’ that maintain life. It’s often referred to as one’s Buddha nature, and is an intrinsic part of the wider universe. The ego likes to think of itself as an independent being; the Buddha self is inextricably linked with the environment on which it is dependent.

Whereas Zen finds expression in sitting silently, Shinto finds expression in matsuri (festivals) when the kami is paraded around its parish. Both religions disdain logic and reason in favour of non-verbal truth. Both have fed off and fed into the Japanese trait for emotional response and wordless communication. Here then may be the mutual complementary nature that has sustained the two religions over the centuries. One is yin and the other yang, both being part of a larger whole. It’s an idea I’d like to explore further in the next post about the role of the sun and the moon in Japanese religion.

The grounds of Ise resemble the dry landscape of Zen gardens. Both seek to symbolically strip away embellishments and externals to arrive at a state of purity.