National

Clandestine Japanese enthronement rite embodies tradition but is marked by controversy

by Reiji Yoshida (Japan Times Nov 13, 2019)

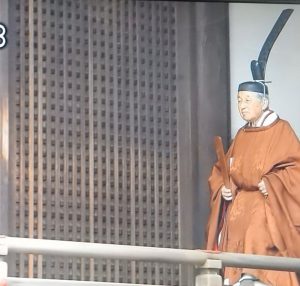

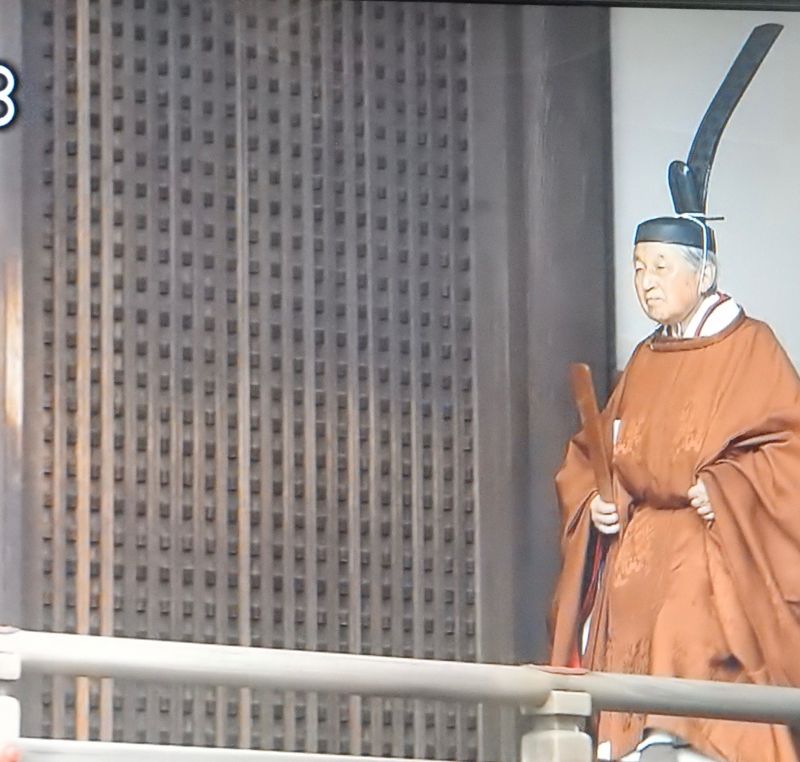

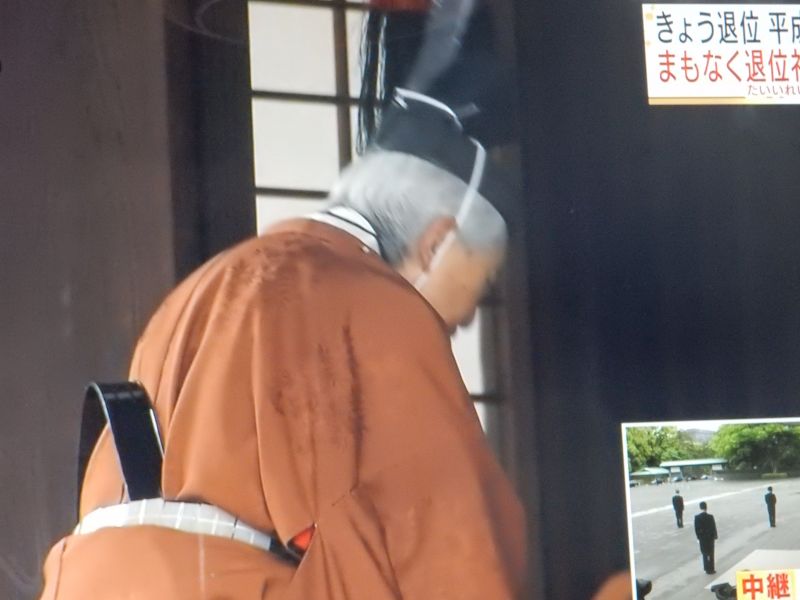

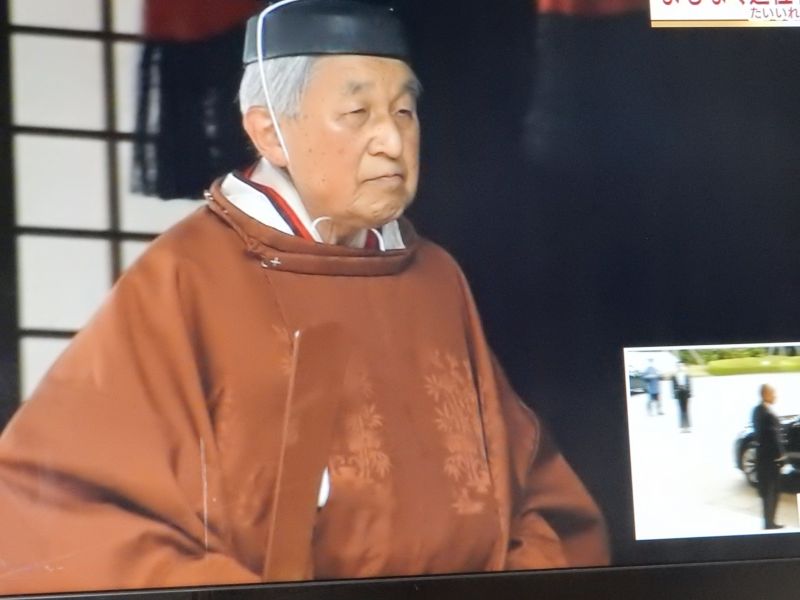

Throughout this year, a series of elaborate ceremonies are being held in Japan to mark the enthronement of Emperor Naruhito and the beginning of the new imperial era, named Reiwa, said to mean “beautiful harmony.”

The Daijosai, the most secretive and arguably controversial part of those ceremonies, was set to begin Thursday evening and continue into the early hours of Friday. The ceremony is a Shinto rite during which a new emperor prays for peace and a rich harvest for the nation.

The ceremony, which originated centuries ago, is mysterious because the exclusive ritual is attended only by the emperor and a handful of female assistants, all wearing traditional-style dress, and according to Shinto beliefs involves deities descending to the ground during the ceremony.

What exactly is the Daijosai, and what will happen inside the two temporary shrines at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo? Here we examine in more detail the Shinto rite set to take place from 5 p.m. Thursday until 3 a.m. Friday:

What is Daijosai?

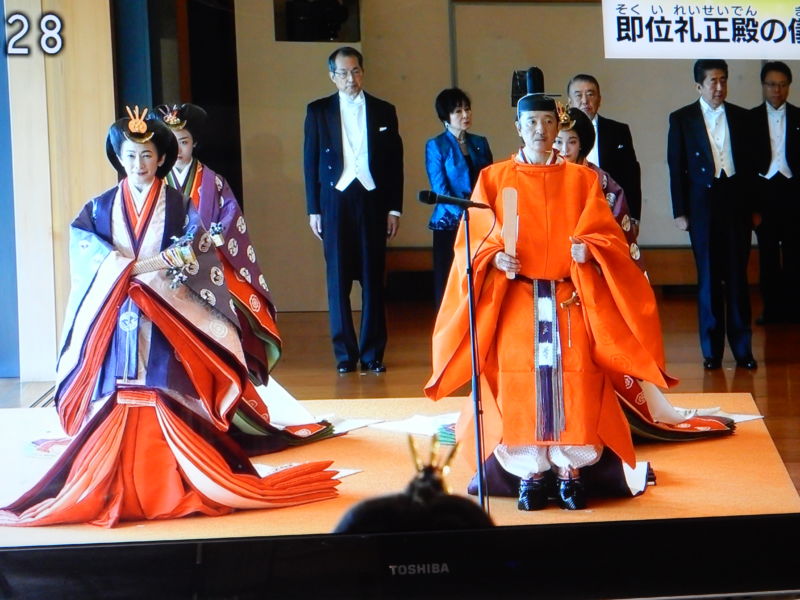

The Daijosai, which can be roughly translated to mean “great food offering ritual,” is the last of the three main imperial ceremonies making the enthronement of a new emperor, following the Kenji to Shokei no Gi in May and Sokui no Rei last month. Compared to the two other events, the Daijosai is a more religious and private ceremony for the emperor and is held in autumn after the year’s rice harvest.

It is a variation of Niinamesai, an annual ceremony in which the emperor offers gratitude for the year’s rice harvest and prays for the peace and prosperity of the nation.

The Daijosai is the first such ceremony following an enthronement, and is considered the most important rite for an emperor.

What’s the origin of the Daijosai?

According to the Imperial Household Agency, the Daijosai originates from the Niinamesai, which is mentioned in the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest existing historical record, which was compiled in 712.

Until the mid-seventh century, there was no clear distinction between the first Niinamesai after an enthronement and other Niinamesai conducted afterward.

Emperor Tenmu, who reigned from 673 to 686, was the first to distinguish between the Niinamesai and the Daijosai, the agency said.

Has the imperial family carried out the ritual every time a new emperor ascended to the throne since then?

No. Although often touted as the world’s oldest monarchy, the emperor lost control of the country in ancient times, and samurai effectively ruled the country for centuries from the late 12th century to the late 19th century.

Hit hard by financial difficulties, the emperor did not conduct a Daijosai ceremony for more than 220 years until the late 17th century.

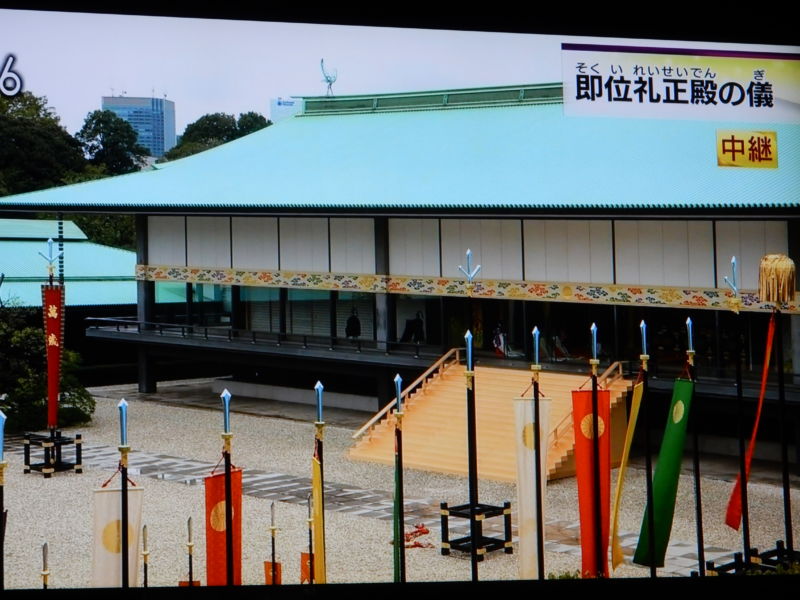

What exactly will the emperor do during Daijosai?For the rite, two temporary shrines called the Yuki Hall and the Suki Hall respectively are set up within the compound of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

On Thursday evening, the emperor will enter the main room of Yuki Hall, the interior of which will be lit dimly by only traditional-style oil lamps. In the room, newly harvested rice, fish, abalones, fruit, chestnuts, sake and other food from across the country will be placed on wooden plates.

The emperor will pick up each food item and place it on leaves, dozens of which will be arranged on the floor, to dedicate it as an offering to Amaterasu Omikami and other Shinto gods that have descended to the room. In Shinto belief, the goddess Amaterasu Omikami is said to be the ancestor of the imperial family.

The emperor then will read out a prayer offering gratitude for peace and the harvest, and will wish for the same for the nation.

The foods are then eaten by the emperor together with the gods in the room. The same rite will be repeated in the Suki Hall, where it will continue until 3 a.m. Friday.

Why does the emperor repeat the same rite in two halls?

The Yuki Hall, located in the east, represents eastern Japan and the Suki Hall western Japan. For that reason, rice from eastern Japan is dedicated to the gods in the Yuki Hall while rice from western Japan is used for the rite in the Suki Hall.

In ancient times, the Yuki Hall in most cases represented the Omi region, which is today’s Shiga Prefecture, while the Suki Hall represented Tamba or Bicchu, which are today’s Hyogo and Okayama prefectures respectively.

For the Reiwa succession, rice from Tochigi Prefecture represents eastern Japan and that from Kyoto Prefecture western Japan. Those areas were chosen based on an ancient-style fortune-telling ritual using sea turtle shells.

In the ritual, a fortune-teller reads signs indicated by cracks on turtle shells heated with fire, and locations of the rice fields are chosen on that basis, according to the Imperial Household Agency.

What is controversial about Daijosai?

The act of the emperor praying directly to Shinto deities, including Amaterasu Omikami, marks the event as highly religious. Some scholars and activists are concerned that the Shinto ritual violates Article 20 of the Constitution, which stipulates the separation of state and religion.

The principle is considered particularly important by historians given Japan’s past militarism in the 1930s and 40s, which was grounded in state-centered nationalism that centered on people’s worship of Emperor Hirohito, posthumously known as Emperor Showa, as a living god.

The Article 20 of the postwar Constitution reads: “No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority … The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.”

The state government plans to spend ¥2.44 billion for the Daijosai, including ¥1.9 billion on construction of the two main shrines and other temporary structures — which will be all dismantled after the planned public viewing.

Hundreds of people have filed a lawsuit against the state government, arguing that such funding violates Article 20 and that their freedom of religion has been damaged.

What does the government say about the claim?

The government at the same time has acknowledged that the Daijosai is more religious, unlike other enthronement-related ceremonies.

For that reason the government is handling Daijosai as a separate imperial activity, rather than a “matter of state,” to allow the emperor’s involvement while respecting the Constitution.

Who will attend the Daijosai this year?

Besides the emperor, only a handful of female assistants are allowed to enter the two halls, to help him, according to public broadcaster NHK.

About 700 guests are invited to wait outside the Yuki and Suki halls during the ceremony. They will not be able to see anything happening inside the halls.

Invited guests include Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, current Cabinet ministers, speakers of the Lower House, the president of the Upper House, Supreme Court judges and dozens of Diet members. No representatives from foreign countries are invited.

Can the general public watch the ceremony live?

No. However, general visitors will be allowed to enter the compound and see the structures used for the ceremony from Nov. 21 through Dec. 8, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Visitors are asked to come to the entrance of Sakashita-mon Gate of the Imperial Palace by 3 p.m.

Map: sankan.kunaicho.go.jp/english/guide/access_map_kokyo.html

***************

For those who wish to read in detail about the sacred space in Daijosai and its connection with Ise Jingu’s twenty year renewal, please see this article by Gunther Niitschke.

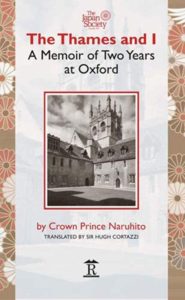

You’re regarded as the high priest of Shinto and chief ritualist of the realm. Your grandfather was considered a living god. Your family line claims descent from the Sun Goddess and has ruled as emperor for 126 generations. With a pedigree like that, what kind of a memoir could you possibly write?

You’re regarded as the high priest of Shinto and chief ritualist of the realm. Your grandfather was considered a living god. Your family line claims descent from the Sun Goddess and has ruled as emperor for 126 generations. With a pedigree like that, what kind of a memoir could you possibly write?