Symbolic night with ‘goddess’ to wrap up emperor’s accession rites

By Elaine Lies TOKYO © (c) Copyright Thomson Reuters 2019.

As published in Japan Today Nov 11, 2019

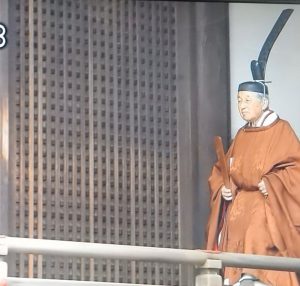

On Thursday evening, Emperor Naruhito will dress in pure white robes and be ushered into a dark wooden hall for his last major enthronement rite: spending the night with a “goddess.” Centered on Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess from whom conservatives believe the emperor has descended, the Daijosai is the most overtly religious ceremony of the emperor’s accession rituals after his father Akihito’s abdication.

Scholars and the government say it consists of a feast, rather than, as has been persistently rumored, conjugal relations with the goddess. Although Naruhito’s grandfather Hirohito, in whose name soldiers fought World War Two, was later stripped of his divinity, the ritual continues.

That has prompted anger – and lawsuits – from critics who say it smacks of the militaristic past and violates the constitutional separation of religion and state, as the government pays the cost of 2.7 billion yen.

WHAT HAPPENS?

At about 7 p.m., Naruhito enters a specially-built shrine compound by firelight, disappearing behind white curtains. In a dimly-lit room he kneels by piled straw mats draped in white, said to be a resting place for the goddess, as two shrine maidens bring in offerings of food, from rice to abalone, for Naruhito to use in filling 32 plates made from oak leaves.

Then he bows and prays for peace for the Japanese people before eating rice, millet and rice wine “with” the goddess.The entire ritual is repeated in another room, ending at about 3 a.m.

Long a secret, the ceremony was re-enacted this year by NHK public television, an unprecedented move scholars say may have been a government initiative to dispel rumors.”There is a bed, there is a coverlet, and the emperor keeps his distance from it,” said John Breen of Kyoto’s International Research Center for Japanese Studies, adding that de-mystifying the ceremony could be a government defense.

“Kingmaking is a sacred business, it’s transforming a man or a woman into something other than a man or a woman,” he said, pointing to mystical elements in Britain’s coronation functions. “So the Japanese government’s denial that there’s anything mystical to it is bizarre, but the purpose is pretty clear – it’s to fend off accusations there’s something unconstitutional going on.”

HOW ANCIENT IS THE TRADITION?

Believed to have started in the 700s and observed for about 700 years, the ritual was then interrupted for nearly three centuries, a gap that Breen said led to the loss of much of its original meaning.

Although believed to have initially been one of the less important enthronement rites, the ceremony gained status and its current form from 1868, as Japan began to turn itself into a modern nation-state, unified under the emperor.

WHAT IS THE FUNDING CONTROVERSY?

At a news conference, the emperor’s younger brother, Crown Prince Akishino, wondered if it was “appropriate” to use public money, suggesting instead the private funds of the imperial family, which would necessitate a far smaller ceremony.

But Koichi Shin, the head of a group of 300 people suing the government to halt the ritual, and demand damages of 10,000 yen each for “pain and suffering”, says that would still not be satisfactory, as the private funds are still tax money.

With part of one lawsuit thrown out by the Supreme Court and another set for hearing after the rite, the court battle is mostly symbolic, as concern over nationalism and the emperor fades.

At then Emperor Akihito’s accession in 1990, protests were louder and bigger, including rocket attacks ahead of some of the rituals, while 1,700 people sued amid harsh media coverage.

“Emperor Hirohito was responsible for the war, but Akihito has done a lot to soften the family’s image,” said Shin, a 60-year-old office worker. “But I think showing these ceremonies on television solidifies the idea of the emperor as religion.”

*********************

For those who wish to read in detail about the sacred space in Daijosai and its connection with Ise Jingu’s twenty year renewal, please see this article by Gunther Niitschke.