Spring is an exciting time of year. After the winter hibernation, nature reawakens in colourful and often spectacular fashion. Plum and cherry blossom are accompanied by daffodil and crocus. Farmers set about planting again, and Shinto hosts a range of festivals dedicated to fertility and success of the year’s new crops.

Promotion of the life force is a central strand of Shinto, sadly overlooked in books and by modern practitioners. One reason is that the reforms of Meiji times did much to sanitise the religion, stripping it of its earthier and uncontrollable elements in order to enforce conformity. Diversity in local practice was replaced by set rituals and an emperor-centred worldview that still prevails.

One of the more obvious examples of the drastic change is the plight of phallic worship. Accounts of the country by Victorian travellers tell of the widespread practice in earlier times, but that many of the phalluses were being removed in the face of Christian criticism that it was primitive and offensive. Japan was intent on joining the Big Powers, not being embarrassed by them.

Yet phallic erection is one of the most vital affirmations of the life force that exists. For those who prefer the old pre-Meiji ways to the new, there are vestiges of the spring time celebration of the ‘life force’ all around Japan. They are manifest in the many shrines that still harbour phallic representations, where they serve not only as stimulants for birth, but as protectors against sexual disease or infertility. They can be seen too in rituals such as 7-5-3, which celebrate the development of children’s growth. They are evident too in cherry blossom parties, where the celebration of nature is enhanced by alcohol and communal feasting.

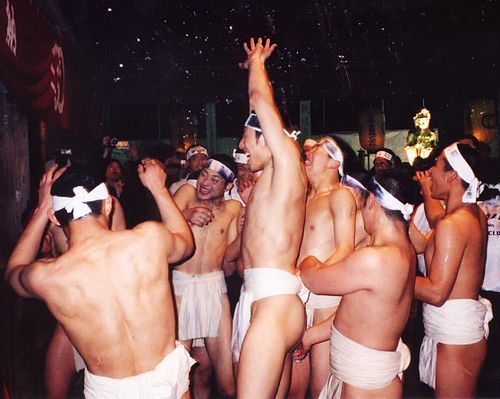

In contrast to the strict adherence to correctness in shrine rituals, the Dionysian side of Japanese culture is manifest in the many wild and sake-fuelled festivals that still retain a local colour. Nothing could be more different from the carefully stipulated niceties of modern Shinto than the spontaneity and communal high spirits of the Japanese matsuri. Here in these unbuttoned festivals the affirmation of the life force can be seen in its most naked guise – sometimes, as in the Hadaka Matsuri below, quite literally.