Normally at this time the Gion Matsuri would be filling Kyoto’s streets, but irony of ironies this year it is not taking place. What’s the irony? Well, it’s a festival that originated and was perpetuated in a desire to dispel pestilence. Just when it’s needed most, you might think, the festival has been cancelled because of Corona.

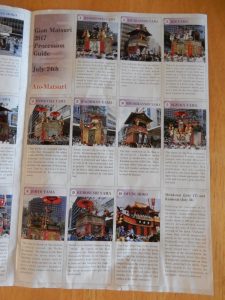

Dating back to 869, the month-long event has been called the oldest urban festival in the world. It climaxes in two parades of stunning floats, though there is far more to it than that. On Sunday, an account of its astonishingly rich diversity was given in a talk for Writers in Kyoto by Catherine Pawasarat, who has a book coming out in August detailing the whole festival.

There are 34 floats in all, and as an indication of the extraordinary wealth of material involved here is an excerpt from Catherine’s forthcoming book focussing on one single float, the Urade Yama.

*******************

Urade Yama 占出山: featuring Empress Jingū

(by Catherine Pawasarat)

Urade Yama shows the third-century Japanese shamaness ruler known as Empress Jingū using fishing as a divining method. She asked the gods to send a fish to let her know if she’d be victorious on a journey to the land of Silla, part of the modern-day Korean peninsula. This took place on Kyushu Island in western Japan. Closest to the Korean peninsula, Kyushu was home to many settlements of immigrants from the ancient kingdoms that predated Korea.

This float’s name, Urade, means roughly, “prophesize and go forth.” Japan’s most ancient texts say Empress Jingū caught a fish, and consequently traveled to Silla [with an army]. With several gods on her side, the texts tell us, she “conquered” it without fighting. She returned to Japan with abundant tribute.

Besides Urade Yama, Fune Boko (“Ship Float”) represents Jingū’s ship on its way to Silla, and Ōfune Boko (“Great Ship Float”) is the ship returning, heavy with gifts. One can’t help but wonder whether it was this remarkable woman’s magnetism that enabled her to win such gains without a battle.

But Urade Yama’s Empress Jingū is prepared for battle, giving us a taste of Japan’s little-known but intriguing history of women warriors, onna-bugeisha. Both the swords she wears are on display in the treasure area before the July 17 procession. The original katana sword is a National Treasure crafted in the tenth century by the legendary Sanjō Munechika, who also created Naginata Boko’s mystical longsword.

Urade Yama’s kaisho treasure display area is unique in that it’s located in the lovely, often peaceful courtyard of a sizable Shintō Shrine. This shrine and courtyard are only open during the Gion Festival, for Urade Yama. The treasures include textiles depicting Japan’s 36 Immortal Poets and its three most famous scenic places, as well as the sweetfish that foretold Jingū’s fate. In textiles based on designs by Maruyama-Shijō school artist, Suzuki Hyakunen, Korean officials and soldiers puzzle at waters encroaching because of divine tide-controlling jewels Empress Jingū used to land victoriously in Silla.

Empress Jingū is famous for being pregnant during her bold adventures in Silla, and for giving birth to a healthy baby boy, the next emperor, Ōjin (see Hachiman Yama), on her return. Therefore she’s considered a protectress of safe childbirth, and amulets are sold here for the same. Over the centuries aristocratic Japanese women used Urade Yama talismans wrapped against their growing bellies to help ensure safe childbirth. After a healthful birth, they gifted their own precious kimono to the deity and her float in gratitude. Thanks to this tradition, at Urade Yama we can see what kind of kimono Japanese empresses and princesses have worn over the centuries. Passed down through generations, the quality and number of kimono a woman had are still considered a measure of wealth. This makes Empress Jingū and Urade Yama wealthy indeed.

(Immigrants from the modern-day Korean peninsula were highly respected in earliest Japanese history. They brought with them technologies like fermentation, ceramic kilns and temple architecture, knowledge like Chinese writing and law, and many other valuable resources. The sacred statue of Empress Jingu wears a noh costume and mask, and holds a curved fishing rod.)

****************

For full coverage of the festival, check out Catherine’s website here. For previous Green Shinto postings, see here, here or here.

of Urade Yama’s luxurious aristocratic

kimono.