Itsukushima Jinja

There’s an attractive pond area in the south-west of the Gosho park which contains a shrine for Benzaiten (or Benten for short). It’s named after the famous Itsukushima Shrine near Hiroshima, and was once part of a residential estate belonging to the prestigious Kujo family, one of the five regent houses close to the emperor whose members served as chief advisors. One of the family’s females became wife to Emperor Taisho.

Towards the end of the Edo Era the Tokugawa shogunate yielded to the demands of the USA to open up the country, though the imperial side led by Emperor Komei were strongly opposed. This led to fierce debate about whether or not to sign the Harris Treaty, and negotiations were held here in 1858 at the Kujo residence (Kujo Hisatada was Emperor Komei’s chief advisor).

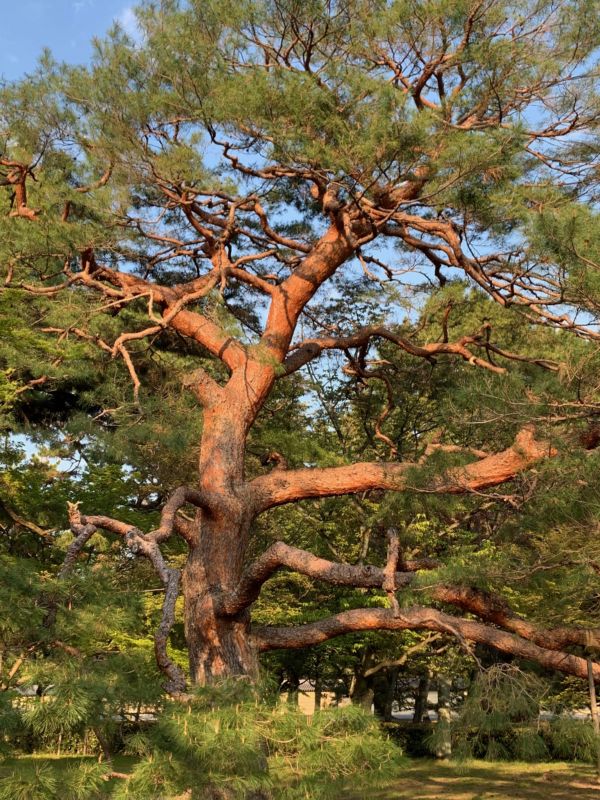

Today all that remains of the estate is the pond with a Tea Ceremony House and a Benten shrine that served as guardian for the Kujo family. It’s said that the island on which the shrine stands was shaped to resemble that of Itsukushima.

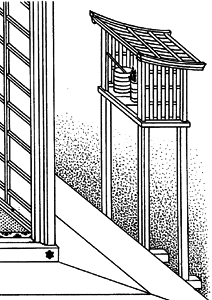

The small shrine bears one striking feature – an unusually shaped torii. The karahafu curve is often seen in shrine architecture, but not in torii. A noticeboard states that it was first built by Taira Kiyomori at the end of the Heian Period, and that it was relocated on more than one occasion, eventually being placed here in Edo times.

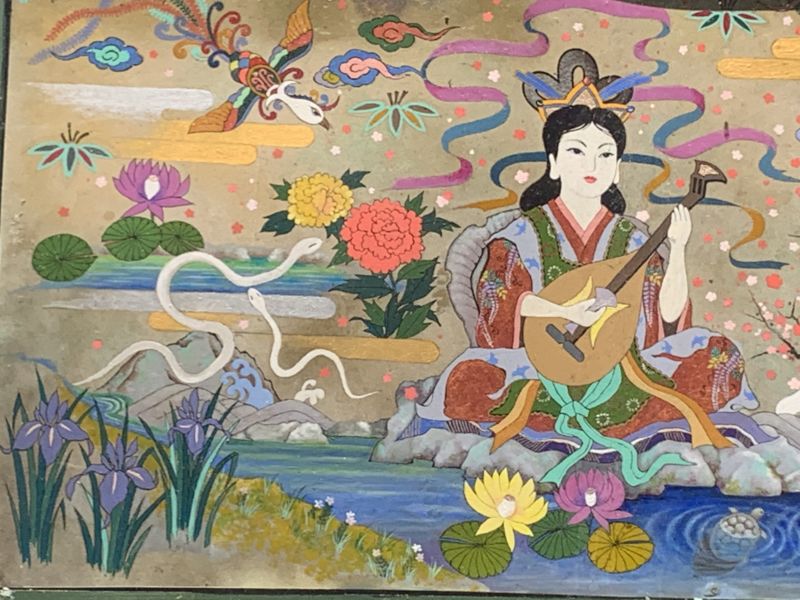

Associated with water and the subconscious, Benzaiten is patron of the arts and creativity. With origins in India, she is served by a white snake and is the only female aboard the Treasure Boat carrying the Seven Lucky Deities. (Click here to read more about them, and about Benten herself.)

Unlike other Shinto deities, the syncretic and foreign origins of Ben(zai)ten means that she is often portrayed in paintings and statues. (Until the arrival of Buddhism, kami were considered to be unseen spirits and consequently there could exist no representations.) No doubt her status as muse of the arts is conducive too, and the shrine’s ema portrays the goddess with auspicious symbols and in creative mode as the patron saint of music.