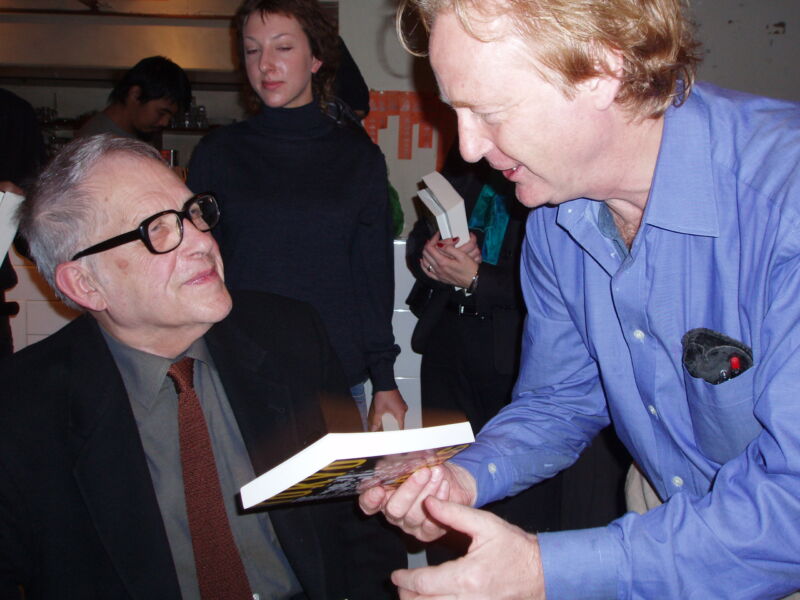

Donald Richie was one of three American giants of Japanese culture in the postwar years, together with Donald Keene and Edward Seidensticker. He came to speak at my university and was kind enough to write a foreword for my book on Kyoto. Like many others, I loved his travel writing in The Inland Sea, and amongst the many thoughtful insights is a passage on Shinto that deserves wider recognition. So here it is, hung around a visit to an out of the way hillside shrine he had come across. (pages 25-27 in the Stone Bridge Press edition)

****************

Many Shinto shrines lie on heights. One goes up and up and up to worship. The steps lead straight into the sky and are always steep. It is work to reach such a shrine. The faithful must arrive puffing, gasping, senses reeling. This is as it should be. One arrives as though new born, helpless, vulnerable. One’s panting sounds in the ears because a shrine is very quiet, quieter than a church. A church is hushed because one is made to be quiet; a shrine is simply quiet. It is so far away that noise does not reach.

You yourself may be as noisy as you please. Gasps for breath, eventual shouts and laughter, are quickly swallowed up. You speak in a normal voice as you walk about, investigating everything, peering behind this door, into that box. The reverent, the hushed, the awed – these have small place in a shrine. If there is any restraint, it comes from nature itself. You may lower your voice, just as you naturally lower your voice in a grove or a gorge. If you feel like it, you impose a willing silence upon yourself.

Shinto prayer is not communal prayer. It is solitary and spontaneous. No one says when to begin or when to stop. You choose your own time. You speak to the gods in the way you might greet your hosts at a party. It is a discreet, friendly, happy, polite prayer.

Apparently no came to pray any more in this small shrine. The stone steps had been forced apart n places by roots of trees grown large after the shrine was built. the only motion in this tangle of bushes and weeds were the large red crabs that, looking already cooked, refused to move, menaced with waving cleft claws, and denied being afraid.

AT the top one is ready for the god. One is reeling, fainting, panting. And there, as though for reward, spread out like a banquet, is a view of the other side of the bay, the sea, the distant farther island, all gleaming in the setting sun, as though cast from bronze and floating on lacquer.

Here at the top it was still day, though below, back toward the village, the sea was clouded and the beach was darkening. The shrine, seen through a line of trees, gleamed a rich yellow, the color of cut wood in sunlight. It was silent. I heard the cicadas the moment they ceased.

Walking through the clinging weeds I crossed to the shrine and stood before the votive box. The god was just inside the closed doors in front of me. I pulled the rope of the god-summoning rattle. The sound was like that of a dry husk shaken. These gods have no bells – the only sound they know is this dusty sound of dried seeds shaken by the winds.

Shinto is nature. Perhaps animism – and Shinto is the only formal animistic religion left – is the true religion. It has roots deep in all of us. One recognizes this. It is the only religion that can inspire the feeling children know when the wind or a rock is made god for a week or a day. Its essence is unknown. The religion speaks to us, to something in us which is deep and permanent.

Once I had sounded the rattle, once its rasping cry, like the quiver of a cicada, had died, once the god was looking from his trellised door way, I was afraid not to give. The votive box looked hungry, its slats like teeth.

The Shinto gods are near us. they prefer money. I dropped a coin; then, not knowing what else to do, shook the rattle again. A dark shape stood for a second against the sky, whirled about me, was a speck of black in the darkening sky, was gone. It was a bat.

****

Climbing slowly down the shadowed tones, I thought of Ise, the greatest shrine of all, the mother shrine, home of the Sun Goddess herself. A visit to any shrine, as humble and forgotten a one as this, leads one to consider such imponderables as life, death. Thoughts of ancient Ise led me to consider another – time.

Time for the West is a river. Down its changing yet forever unchanging length we float. In the East, however, the river is more. a symbol for life, our earthly span, the ukiyo, than it is for time itself.

Time has no symbol in this Asia where almost everyone, at least formerly, lived in a continuous and unvarying present. If it had one, it might be a symbol as startlingly up-to-date as the oscillating current. The reason this occurs is Ise – not only one of the great religious complexes of the world but the only answer yet discovered to man’s universal wish either to invent the perfect perpetual-motion machine or, else, to stop time entirely.

The way to stop time, the Japanese discovered, is letting it have its own way Just as the shape of nature is observed, revered, so is the contour of time. Every twenty years – and for over a thousand years – the shrine at Ise is razed and a new one is erected on an adjacent plot reserved for that purpose. After only two decades, the beam-ends barely weathered, the copper turned to palest green, the shrine is destroyed. Only twenty generations of spiders have spun their webs, only four or five generations of swallows have built their nests, not even a single blink has covered the great staring eye of eternity – yet down come the great cross-beams, off come the reed roofs, and the pillars are carried off to be reused in other parts of the shrine grounds.

On the adjacent plot is constructed a shrine that is in all ways similar to the one just dismantled. More, it is identical. Something dies, something is born, and the two things are the same. This ceremony, the sengushiki is a living exemplar of the greatest of religious mysteries, the most profound of human truths.

And time at last comes to a stop. Forever old, forever new, the shrines stand there for all eternity. This – and not the building of pyramids, or ziggurats, not the erection of Empire State Building or Tokyo Towers – is the way to stop time and make immortal that mortality which we cherish.