Every year there’s a Shinto festival held at the Sumiyoshi Shrine in Uto City, Kumamoto Prefecture, to an English woman called Kathleen Drew. (Her full name was Kathleeen Mary Drew-Baker.) It’s a curious phenomenon which reminds us of another foreigner celebrated by what has been described as a ‘religion of Japaneseness’, namely American inventor, Thomas Edison (featured here).

Kathleen Drew became known in Japan as Mother of the Sea for her research on edible seaweed. An article she wrote in 1949 in the scientific journal Nature came at a time when the Japanese economy was in dire straits and there was a failure in the seaweed crop.

The information provided by Kathleen Drew was picked up by Japanese scientists and passed on to fishing communities which enabled them to cultivate nutritious nori. From near starvation the fishermen turned around the seaweed industry to become part of Japan’s rapid economic success. Now it’s said seven billion sheets of nori are produced a year, and riceballs wrapped with nori are Japan’s favoured comfort food.

Out of gratitude the seaside community of Uto put up a monument in 1963 to honour the English woman and inaugurated an annual festival called Drew-sai which draws some 100 people. A norito prayer in Japanese is addressed to her, and a tamagushi sakaki branch offered to her spirit. Although not a kami, she is considered an Onjin to whom the community is indebted.

What does this little-known oddity have to tell us about Shinto? For one thing it shows the vital role that gratitude plays in the religion and in Japanese culture as a whole. More than that though, it shows how Shinto acts to preserve historical memory. Kathleen Drew never visited Japan, but she’s become part of the national consciousness. Shinto serves many functions and by sacralising the past it reinforces the strong bond of communal identity. In this way, ironically, gratitude to a foreigner turns out to deepen awareness of Japaneseness.

(All photos courtesy Wikicommons)

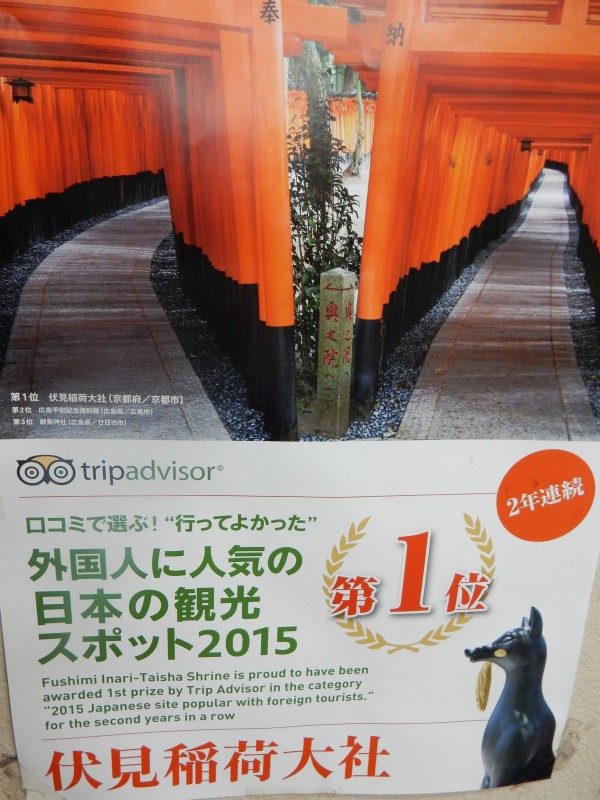

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.

On Sunday I took an out of town visitor to a combination of Tofuku-ji Zen temple and the popular Fushimi Inari shrine. They are both in the south-east of Kyoto, a mere twenty minutes walk apart, and the Zen-Shinto combination makes a wonderful introduction to the world of Japanese religion. The large solemn buildings of Zen provide a contrast with the colourful bustling crowds at Fushimi, and yet the similarities are striking.