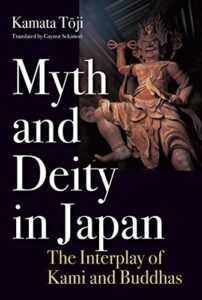

Book review of Myth and Deity in Japan (2009) by Kamata Toji (tr Gaynor Sekimori)

For followers of Green Shinto, this is very nearly the perfect book!

First of all, it is written by a leading scholar and practitioner (emeritus professor of Kyoto University). It positions Shinto as an East Asian religion, not an indigenous religion. It is firmly in support of syncretism, viewing the marriage of Shinto with Buddhism as integral to Japan’s spirituality. It acknowledges the vital input of shamanism and Confucianism. And it takes a very critical attitude to the Meiji reforms, which artificially split Shinto from Buddhism, led to the banning of Shugendo, destroyed local diversity, and replaced kami worship with emperor worship. The damage done by the Meiji ideologues continues to the present day, but as an alternative the book promotes the spirituality of everyday Japanese, as outlined by twentieth century folklorists referred to as Neo-Nativists (about whom more below).

So what makes the book less than perfect? The answer lies in the hard to digest middle chapters, where the reader is overloaded with unnecessary historical detail. Here one has to bear in mind that the book was written for educated Japanese, who would be expected to be familiar with the names and movements.

Chapter One introduces the notion of what a combinatory religion involves, and Chapter Two describes what happened when Buddhism arrived and mixed with the native kami. So far, so good. However, in Chapter Three and Chapter Four, the narrative goes into a lengthy explanation of developments during the Heian and Medieval Periods. This is not easy reading, nor is it helped by some clunky language more suited to a scholarly work (indeed, the book sometimes reads as if it has been pieced together from academic papers).

Chapter Five, which investigates Nativism in late Edo times, injects greater relevance by investigating the influence of leading figures on the religious reforms of Meiji times. This includes a useful overview of the work of the influential oddball, Hirata Atsutane (1776-1843). Whereas his more famous predecessor Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) focussed on this world, Hirata investigated the spirit world including tengu and yokai. In other words Motoori looked to mono no aware, Hirata to mononoke (the pathos of worldy transience in the case of the former, as opposed to the vengeful spirits of the latter). However, it was Hirata’s ‘Japan first’ message that was the decisive element in shaping Restoration Shinto, which later segued into State Shinto and the ideology of WW2.

Kamata is particularly good at depicting the confused meanderings of the Meiji government as it sought a new religious order to bolster the emerging nation. It resulted not only in the banning of Shugendo as superstitious, but also the outlawing of Folk Shinto. It showed just how far removed from ordinary people’s religion the politicians had become. The assertion that Shinto be used as a tool of state meant that it was not classified as a religion, and this resulted in such absurdities as the Shinto shrine of Izumo Taisha being regarded as a vehicle for state rites while the Shinto sect of Izumo-kyo which honoured the same kami was seen as a religion.

Chapter Six not only brings us right up to date but puts forward a surprising agenda for the future, quite different from that of current orthodoxy. It is based on what is called Neo-Nativism, featuring two key figures, the founder of folklore studies, Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) and the more literary minded Orikuchi Shinobu (1887-1953). Between them they promoted folk studies based on common people’s beliefs. This bottom-up approach differed radically from the top-down approach of the Meiji government.

At the end of the book, it is Orikuchi Shinobu in particular who takes centre stage, with no fewer than ten pages devoted to his life and work. Orikuchi had an interest in words and incantations, particularly with regard to pacifying the spirits of the dead and fostering rebirth. To this end he investigated performing arts and festivals, areas in which Kamata Toji himself actively participates (he plays the stone flute and writes Shinto songs). Moreover there is a suggestion that as a man who excelled in many fields, Orikuchi represents the cultural essence of Japan. Not only is he celebrated for his folklore work, but he is also in the words of Kamata, “a surprisingly good novelist, perhaps among the finest Japan has produced” (p. 143). That is some endorsement, and the championing of such a figure is an intriguing way to end a book that seeks to defend pre-Meiji Nativism and promote as a force for peace the spirituality of ordinary Japanese.

Some key quotations –

• About syncreticism: “The idea of kami-buddha combination (shinbutsu shugo) is at the core of Japanese spirituality.” (p.vii).

*About the Meiji Restoration: “It was a religious reformation from above that was highly inconsistent with people’s personal ideas about the kami and the buddhas.” (p. 124) “People”s fundamental understanding of kami did not essentially change as a result, but great changes came about institutionally.” (p.125)

* Shrine merger law of 1906: ‘a great mistake’ (p. 132).”The shrine consolidation policy led to the decline of local culture, disrupted community life, and ultimately destabilized the very foundations of Japanese society.” (p.132)

* Meiji Shinto: “In stipulating that the emperor was divine and came from an unbroken imperial line, the Meiji Constitution created a distinctive Japanese state system that grafted a Prussian model of absolute monarchy onto the ancient ritsuryo-type system, in the process setting up a chimerical absolute monarchy.” (p.131) (According to Greek mythology, the chimera was a grotesque creature made up of many parts.”) (p. 130)

* Buddhism and Shinto: [Buddhism] is basically humanistic, in comparison to Shinto, which born from the plainest of origins, means living with awe of nature, sensitive to the beauty, harmony, and sacred energy within it.” (p.180)

* The future: “A new kami-buddha combination – a new coworking between Shinto and Buddhism – may be necessary.” (p.181) “Searching for a common human base and bringing it to life represent, I believe, the future of spirituality and the spiritual movement.” (p.181)

About the author (The following is taken from Zen 2.0)

Born in Anan City, Tokushima Prefecture. Was interested in Mythology since age of 10. Started poetry at age 17, and became interested in Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism, and other local folk beliefs.

He has climbed Hiei Mountain 560 times as a practitioner of Shugendo. Credit withdrawal from his doctorate at Graduate school of Kokugakuin Faculty of Letters, majoring in Shinto, and credit withdrawal from doctorate from Graduate school of Okayama University Medicine Department Graduate School of Social Environmental and Life Science. Currently, specially appointed professor of Grief-care institute and Sophia University, Honorary professor at Kyoto University, and visiting professor at the Open University of Japan. Representative Honorary Director of NPO Tokyo Freedom University. Representative Director of the Institute of Emei Yojo Culture Training(emei-japan.net), Chairman of Kyoto Traditional Culture Forest (Dento Bunka no Mori) Promotion Council, Philosopher in religion, folklore, Japanese thought history, comparative civilization. Doctor (literature, Tsukuba University). Plays the traditional stone flue, side flute, and conch horn. Shinto Song writer, Poet.