Our friend, the scholar Robert Wittkamp, has posted an illuminating paper on academia.edu posing the question, ‘Why does Nihon Shoki possess two books with myths but Kojiki only one’? (Click here to see the original paper. Last year he published a longer work on the subject in German: Robert F. Wittkamp, Arbeit am Text: Zur postmodernen Erforschung der Kojiki-Mythen, Gosenberg: Ostasienverlag 2018.)

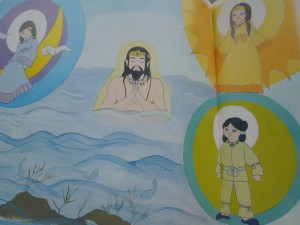

Kagura featuring Ninigi no mikoto, who first descended from heaven to Japan

My initial reaction to Robert’s question was that the answer must be because Nihon Shoki (720) is a historical record of episodes with variant readings, whereas Kojiki (712) is a slimmed down propaganda piece to bolster the mythological roots of the imperial family. The former would obviously be longer than the latter.

However, Robert’s paper answers the question in a much more layered and informed manner. He begins by dividing the myths into two main groups: the southern line from South China, Polynesia and the Pacific, as against the Northern Line from Siberia, Korea and North China.

The southern line is horizontal and concerns the kuni tsu kami who inhabited Japan in early Yayoi times. Their origins lay overseas, hence there are sea myths with paradise somewhere beyond the horizon (one can read about them in Carmen Blacker’s Catalpa Bow).

The northern line, however, is vertical in orientation, with descent from ‘heaven’ (i.e. Korea) by ama tsu kami. This type of myth has roots in Siberian shamanism and looks upwards or downwards to origins. They are more recent in time, arriving as conquerors. To my surprise, Robert suggests this occurred in the fourth century when there was upheaval on the continent with sixteen kingdoms in northern China and a request by Paekche to help fight Koguryeo. (I would have presumed it happened much earlier than that, with the coming of the new Yayoi civilisation in the centuries around year 0.)

Chamberlain’s translation of The Kojiki was the first to open up the stories of Japanese mythology

As Robert notes, important to an understanding of Japan’s myths is the situation of the rulers who ordered their compilation (Tenmu and Jito). They ruled at a time before the title of tenno (emperor) was used and they aspired to greater authority, being dependent on the support of powerful families and feudal clans. (Though Robert doesn’t mention this, Temmu was a usurper and therefore on shaky ground in terms of legitimacy.) By showing ancestral alliances and subordination in the past, it was hoped that the myths would bolster the standing of the rulers.

A key episode in all this is the episode in the myths known as Tenson Korin, when the heavenly kami descended onto Japan. There exist six different versions of this event – one in Kojiki, the main version in Nihon Shoki togetther with four different variants.

Today it is generally assumed that Amaterasu gives the order to her grandson Ninigi-no-mikoto to spread the benefits of their civilisation to earth (a colonial rationale still used today by powerful countries to invade the weak). However, as Robert points out, three of the six extant versions feature Takami Musuhi as issuing the command (Nihon Shoki main version, plus variant 4 and 6). In these three versions it is Takami Musuhi who is the great ancestor of the imperial line. The names of descendants are different. (The usual reading is Takami Musubi, but Robert who is an expert in early Japanese texts prefers Musuhi.)

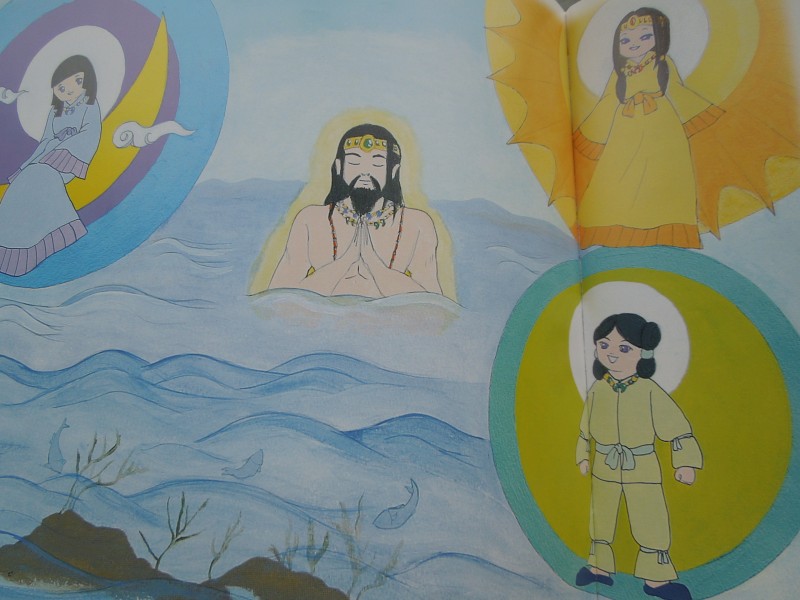

Ame no Uzume whose dance drew a curious Amaterasu from her cave

According to Robert, “Kojiki adds the elements of the two lines together. Consequently it can be described aa ‘ntegration type'”. Later it integrates too the Ise myths into the Amaterasu theme to make one overall narrative, fixing her as the great ancestral spirit. An intriguing conclusion to be drawn from this is that Kojiki may well have been a later compilation than Nihon Shoki, even though it was published eight years earlier.

The question about why Nihon Shoki has two books and Kojiki only one still remains, however. Here Robert suggests that the answer has to do with Nihon Shoki drawing a difference between the Takami Musuhi line in Book One and the Amaterasu line of Book Two. Kojiki on the other hand “tries to connect them and to create a single and coherent narrative.”

At the same time Kojiki puts much greater stress on promoting ties with distant clans away from the capital. The Izumo myths are an example. Robert goes into detailed statistics about the difference between the ancestral groups mentioned in the two books, and his conclusion is that, ‘The Kojiki puts much weight on the powerful groups around Yamato and demotes the muraji and banzo groups close to the Court”.

And here, brilliantly, Robert solves one of the most intriguing puzzles about the myths: why for many long centuries was the Kojik almost totally forgotten (interest was only revived by the historical work of the Kokugaku scholars in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries)?

The answer Robert suggests is that the Fujiwara clan, who rose to dominance after the publication of the myths, did not care for their relatively lowly level played by their ancestors in the myths. The book was therefore put to one side and neglected by nearly all save the imperial household.

The rock cave myth still continues today to play a vital role in Japanese culture and imperial legitimacy

In 2012, to celebrate the 1200th anniversary of Kojiki (712), NHK commissioned a version of the Hyuga cycle of myths, central to the putative descent of the imperial line from heaven.

In 2012, to celebrate the 1200th anniversary of Kojiki (712), NHK commissioned a version of the Hyuga cycle of myths, central to the putative descent of the imperial line from heaven.