The previous Green Shinto posting announced a new hokora shrine planned for Upstate New York. One of the organisers, Fukiko Ostensen, has kindly agreed to answer questions about the project in the hope of helping others who may be similarly inspired.

A pond across from where the hokora is going to be established. The Dalai Lama said it houses a huge Naga spirit, and since Sukunabikona also has a dragon form it is thought to be appropriate.

***************

1) When and how did the idea for a hokora first arise?

(Fukiko Ostensen) Last year, my dear friend and business partner, Mayumi Motoki (Mami), started receiving messages from above (Ten 天) saying we should create a shrine in Upstate New York. She often receives interesting spiritual messages, but this one felt like it was beyond our ability to facilitate at first. So, it remained just an idea for about a year.

Then this spring, we got together with local author, friend, and supporter Maya van der Meer, who was immediately on board with our vision. Maya has often felt there would be tremendous benefit from having an attended dragon shrine in our mountains, where stone serpent effigies that map the constellation Draco have been discovered. Dragons (ryū 龍) are highly respected in Japan, considered as benefactors and protectors of humankind; powerful and wise guardians. They are often associated with Shinto shrines.

The three of us meditated together, deepened our commitment to the project, and asked for guidance. Within a month, everything came together! We connected with Seiji Yamamoto sensei who generously agreed to come from Japan to consecrate the shrine with the powerful, healing deity Sukunabikona (少彦名神), who appears in both human and dragon form. We also found the perfect location at Menla Retreat Center in the heart of the Catskill Mountains.

2) What is the main purpose of your project?

We do various activities based on our heritage to benefit the local communities, like serving Japanese style fermented foods, providing healing arts, hosting seasonal events, and volunteering at local schools and libraries. Our initial thought with this Shinto shrine was to create an auspicious bridge or portal between Japan and America to support our activities. On a larger scale, of course, our aspiration is that the hokora serves to facilitate peace and harmony on earth.

3) To start a shrine or hokora a priest is needed. How did you go about finding a sympathetic priest?

This was the biggest obstacle at first for us. We didn’t know how to go about trying to establish a shrine on our own. When we connected with Seiji Yamamoto sensei through an acquaintance in Japan, all the problems we were facing were solved!

Yamamoto sensei teaches Seitai body work and lucid mediation (明想) methods to the group of students at Aiko-ryu Kiko Seitai. He is also adept at Feng Shui, divination (易) and Old Shintō (Koshinto) tradition. Despite his busy schedule, he agreed to come to America to conduct the sacred ritual of welcoming the deity and properly enshrining him. His sincere interest in supporting this project has given us the energy and confidence to keep going.

4) How was the kami decided?

Even though Mami received the message of making a shrine, we weren’t sure which deity to enshrine at the beginning. Another friend of ours in Japan, who is very knowledgeable about Shinto, advised us to enshrine Sukunabikona (少彦名神), knowing we work with medicinal plants, fermentation, and women’s health. Once the name of Sukunabikona came to us, we received many confirmations that it is the right deity for us.

Then, Yamamoto sensei received a message from the deity directly (goshintaku) when he visited the Sukunabikona shrine in Osaka a couple of days after our first virtual meeting. Sukunabikona gave direct guidance, saying, “I will come where the land is red, looking up a black mountain.”

We soon found the location for the hokora in a pristine forest in the middle of the Catskill State Park, surrounded by unspoiled wilderness. The land, considered sacred by Native Americans, contains red clay, and faces the peak of Panther Mountain. It is the site of the Menla Retreat Center in Phoenicia, NY. The leadership and staff there have been open and welcoming to the project because Menla means “medicine” and the shrine’s purpose aligns with the spiritual and healing retreats offered year-round at the center. The idea of having a dragon companion for Menla’s resident naga, a serpent creature the Dalai Lama saw during one of his visits, is also very exciting.

5) How about the size of the hokora, and where will it come from?

Initially, we thought we had to find a specialized carpenter who could build a small shrine in Japanese style, and were struggling to find one in our area. Then, we learned we could enshrine the deity in a natural rock according to the Koshinto tradition. We searched the Menla property and found a relatively small rock to become a hokora. Yamamoto sensei confirmed the rock, naturally deposited during the time of glacier melt, has a very good energy.

6) What are the costs and how have you funded the project?

We have organized a grassroots effort to raise the funds for this project.

The major expense is the transportation cost for Seiji Yamamoto sensei, his wife, and disciple from Tokyo, Japan. They are staying here for 3 nights and 4 days as the teacher’s schedule is tight. Other expenses include preparation for the ceremony, a large wooden sign about the hokora and the deity, offering materials, and the cost for future maintenance.

We have launched a GoFundMe campaign, but it has been difficult to reach people who share the same interest and passion as we do. Additionally, we have also been organizing events in our local areas to raise funds. We are having fun with it, but would love more international support!

7) Your shrine will not be part of Jinja Hocho (Association of Shinto Shrines? Is that a concern, or not?

It is not a concern for us, mainly because having a shrine/hokora in the United States is a unique situation that needs to function outside of ordinary Japanese formalities.

8) Finally, do you have any advice for others thinking of doing something similar?

Mami says “You have to be almost an idiot (あほ) or extremely optimistic to think of doing a project like this.” She advises that if you are called to do something like this, “Surrender to your passion and do not overthink it. Also, it is very important to have a group of like-minded, good friends and supporters to work together. A project like this is large and serves the community in the long run.”

*********************

To donate or contribute to the project, please click here.

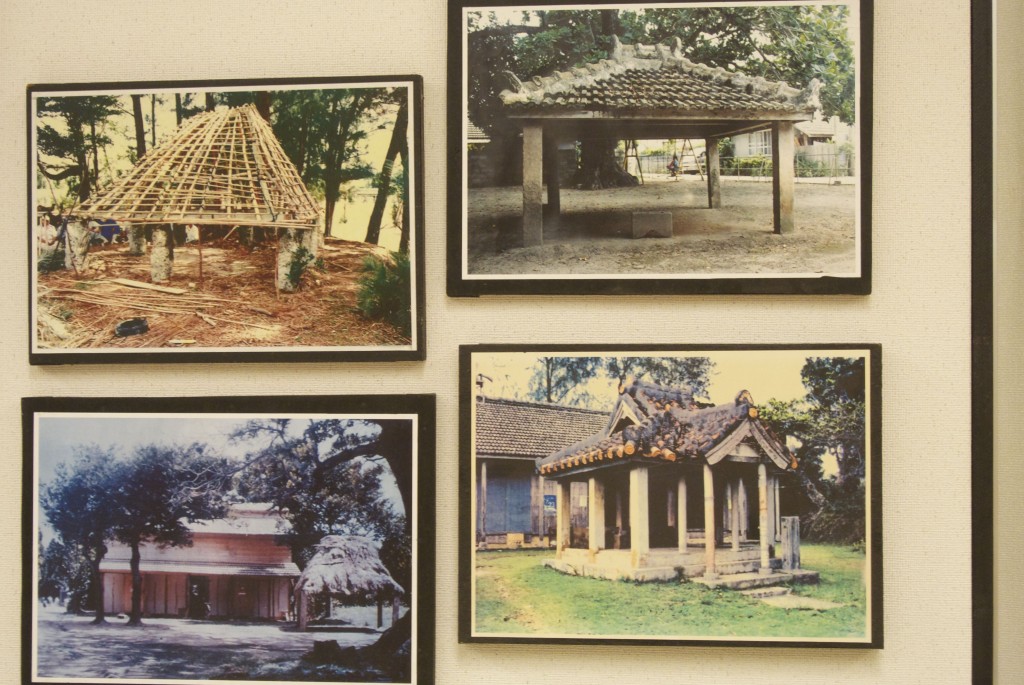

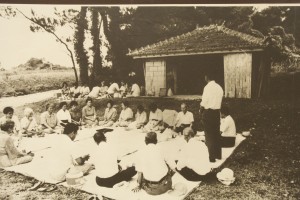

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.