The highlight of today’s parade is the turning of the fixed wheel ‘hoko’ floats at Kyoto’s main intersection

This year’s Gion Festival happened to coincide with a three-day weekend, thanks to the public holiday today (July 17, the day of the main procession). It meant extra large crowds and extra large numbers of police, who for the first time on the Yoiyama evening insisted on one-way directions for the milling throng. In methodical Japanese fashion, anyone heading the wrong way against the flow of people was quickly hauled out and pointed in the right direction.

One of the protective ‘chimaki’ talisman on sale

The crowds were also noticeable for the increased number of foreigners this year. On a rough count, I estimated around every twentieth person was non-Japanese. And at least one of the salesman at the ‘yatai’ stalls was a foreigner with a Kansai accent, doing a brisk business with stretch ice-cream.

Because of the increased numbers of tourists, the authorities have gone out of their way to make the festival more appealing by adding features such as small theatre shows and maiko serving beer in front of Yasaka Shrine. For non-Japanese there was also a very useful free leaflet being handed out in English with one of the best festival explanations I’ve seen.

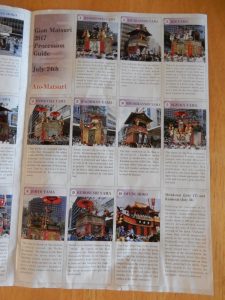

A colourful map gives an overview of the 33 floats and their locations (each downtown neighbourhood maintains and exhibits its own float). There are also detailed explanations of aspects of the festival, such as the special music called Gion Bayashi. This is played with gong, drum and flute. Musicians begin practising when young, mastering all three instruments, and the power of their playing is said to be an important element of the festival.

Another item covered is the ‘chimaki’ protective amulets attached to the front of houses to ward off pestilence during the year. The origin is said to date from when the deity Susanoo lodged overnight at the home of Somin Shorai. Though his family were poor, they gave Susanoo warm hospitality, and in return the deity promised their descendants protection from disease, offering them a bundle of cogon grass to wear around the waist. As a result, cogon grass is used today for the protective ‘chimaki’.

Overview of the 10 floats, with descriptions, that are involved in the Ato-Matsuri (on July 24)

The leaflet also notes that folding screens and scrolls are on display in some of the old houses (though I’m told the number of such displays is greatly reduced as a result of people ‘misbehaving’ by touching exhibits, crossing lines, or shouting in drunken manner etc). Each float also offers for sale its own good luck charm, dedicated to the deity of the float and with its own particular tradition.

Finally, the leaflet gives a detailed description of the two types of floats. One is the Yama, with 14 to 24 carriers, which has a sacred pine tree, a display and carrying poles. The other is the Hoko, which weights 7 to 9 tons and has a long spire like pole stretching up 25 meters from the ground. These floats have large wooden wheels and are pulled by 30-50 people, directed by two men standing on the float itself. Musicians sit on the second floor, and above them are four roof riders who make sure the float steers clear of power lines and other obstacles. Decorative curtains and tapestries hang over the sides.

The distinctive identity and history of each float is neatly given in pages that separate the floats into two parts: firstly, the 23 floats involved today in the Saki-Matsuri (Before Parade on July 17th). Secondly, the ten floats involved in the Ato-Matsuri (After Parade on July 24th).

Four key moments are identified as follows: 1) the festoon cutting ceremony, involving a chigo (sacred child) cutting a straw rope to symbolically represent entering into the spirit world; 2) Lot Check, when each float has to ritually present the document certifying its place in the parade; 3) Float Turning, when bamboo or poles are inserted beneath the fixed wooden wheels of the hoko floats in order to enable them to turn; 4) Disassembly, when after the parade the floats return home and are disassembled to ensure the spirits of disease that have accumulated are not released.

Full marks and gratitude to the Gion Matsuri Yoiyama Council who produced this useful free guide to the annual display of people’s power in the old imperial capital!

The order of floats in the parade is chosen by lottery, and one of the ritual moments in the proceedings is the ‘Lot Check’ when a representative has to show the official document to the authorities.

One of the Chigo (sacred child) that symbolise purity and play an important role in the festival