Disused and untended, the shrine buildings have been abandoned to nature

The main part of Oiwa Jinja is the upper section, for it contains the sanctuary with altar and goshintai (spirit-body) of large and small rock. As far as I could tell, this was elemental Shinto as it used to be in ancient times before the religion was co-opted for imperial purposes. Formless and nameless, the kami is here manifest in a natural object that serves as a focus for worship – or used to serve as focus. It suggests a link with prehistoric practice and makes the shrine all the more fascinating.

To the side of the Sanctuary stands another torii decorated by Domoto Insho, together with an impressive avenue of stone lanterns. There are also many examples of the otsuka characteristic of the Inari faith, whereby stone altars with individualised names of the kami are erected by devotees. The names of donors indicated that many belonged to a fraternity named Osaka Tokki Kouchuu.

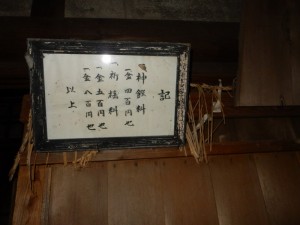

A notice in the abandoned shrine office gave prices that seemed to date from the Taisho period

The general impression was of a shrine that until very recently had been a flourishing enterprise. A bright red lacquered torii which looked relatively new was dated 1999. A stone lantern bore an even later date, donated in 2014. How had the shrine fallen into such decay?

The abandoned shrine buildings stood forlorn, and on the shuttered shrine office was a small handwritten notice saying that following the departure of the long-serving priest in Nov. 2014, there were no more rituals or services. It was dated Jan 2015, and an address given for someone called Kubo Yoshio, the ‘shukyou houjin’ (person legally responsible).

Along the main approach were more stone altars, and we exited onto a deserted dead-end road and headed downhill, stopping to make enquiries of some farmers. They knew little of the shrine, but thought there was no ujiko (parishioners group). At the bottom of the hill stood a kindergarten, and I wandered in to ask if they could help us. Again they knew little, but they did have a brochure of the area with a brief account of the shrine.

According to the brochure, the shrine was started by the Kii clan mentioned in the Yamashiro fudoki (accounts of ancient times). They had apparently been pushed out of their original Fukakusa area by the Hata clan, who had established a shrine at Fushimi Inari in 711. The Kii relocated southwards to Oiwa Hill, which became their tutelary guardian (hills overlooking areas where clans lived usually became their holy place of worship).

In the Onin War (1467-1477) the shrine had been destroyed and all the records lost. Apparently it stayed that way until the Meiji Restoration, when the Kubo family restored it (still today there are many Kubo living in the adjacent area).

From ancient times the shrine had been known for its power to heal serious illness (especially TB). Those who had come here to pray included the mother of Kyoto artist, Domoto Insho, and this explained the two torii that he had decorated and donated. One had been donated in 1952 when his mother was still alive, and the other in 1963 after she had died.

(An inscription on the back of the larger torii mentioned a male aged 70 and a female aged 95, both born in the year of the rabbit, presumably a reference to Domoto’s parents. On the smaller and later torii is an eerie depiction of a woman with no legs (Japanese spirits are by tradition legless.)

Because the brochure had been produced a few years earlier, there was no reference to the shrine’s difficulties or abandonment. I was eager to learn more, and so rang the author of the brochure who said his informant had been the priest running the shrine, named Tsuji Shozo. However, he had no contact number and no information about whether he was still alive.

This was all very fascinating, but I was intrigued by what happens to shrines that have been abandoned. How and why had it been abandoned, anyway? Perhaps the local ward office would have some answers for me, I reasoned, and headed off to see what they had to say. But what they told me only served to deepen the mystery….

The path up to the upper section of the shrine was attractive and well structured.

The shrine buildings were in a bad state of decay…

Yet the altar was still in pretty good shape.

Behind the altar is the sacred rock that served as the object of worship, together with fox guardians and a small torii

There was another torii decorated by Domoto Insho, but not so grand as the one in the lower section

In the surrounding woods were stone altars with individualised names of Inari.

There were some appealing Inari subshrines too

**************************************