Power spots have been discussed before on Green Shinto. Popular with New Agers, they are welcomed by progressive shrines for the increase in visitors. On the other hand, official Shinto views them with suspicion because they distract from the upholding of Japanese heritage and imperial values to which post-Meiji Shinto is committed. If you’re visiting Ise Jingu to absorb the energy in the woods, you many neglect to pay respects (and money) to the putative ancestor of the emperor.

Think of it in terms of authority. Power Spots are based on direct communion with nature. Open, democratic, pluralistic. Shrine Shinto by contrast is based on a hierarchy with priestly privilege and regulated ritual. Power Spots place power in the spirit of place; Shrine Shinto looks to shrine tradition. For New Agers authentic experience is paramount; for orthodox Shinto it’s subjugation to the communal bond.

An article in Savvy Tokyo highlights the popularity of Power Spots for young Japanese. Given the popularity of paganism and New Age spirituality in the West, it’s surprising that Power Spots in Japan have not caught on in a bigger way with foreign tourists. We’ve already seen a rise in interest in Shugendo tours and walks along pilgrim trails such as Kumano Kodo or the Shikoku 88 Temples. When the Covid crisis is over, perhaps we’ll see an upsurge in spiritual tours to the Power Spots of Japan too.

*********************

Power Spots: The Japanese Way To Recharge Your Mind

Take Care Of Your Life Force By Visiting A Tokyo Power Spot

By Erika van ‘t Veld | June 30, 2020 |Savvy Tokyo

Bathe in the energy of these power spots in and around Tokyo to rejuvenate and recharge your mind and body.

A power spot (パワースポット or pawa-supotto in Japanese) is an area where spiritual visitors can take in the energy of the Earth and experience healing, generate good luck, or rejuvenate a tired body and soul. You might have heard about them as “energy spots” or “energy vortexes.” A staple of Japanese tourism guidebooks, they’re more discrete outside the country. Global power spot examples include Stonehenge in England, Sedona, Arizona in the U.S.A, and Uluru (formerly Ayer’s Rock) in Australia.

In Japan, power spots are often known as sacred places where gods come to walk the Earth, so they often coincide with shrines and temples. Many Japanese tourists who value the mind and spirit travel to power spots every year, which is why many articles introducing strong power spots across the country are published around New Years, like this one from Jalan News (Japanese only).

Why visit a power spot?

Power spots are all places where visitors can pray for good luck, and bathe in healing energy to improve their well-being. According to power spot experts—many who are astrologists and psychics and especially in-tune with the Earth’s energy—, some power spots have different benefits to offer its visitors. Similar to shrines with different deities in Japan, some power spots are famous for their physical healing powers, while others are best to visit for bringing luck in love or at work.

Power spot skeptics

As with any spirituality-based notion, many skeptics dismiss power spots as being figments of imagination. Just remember the benefits of visiting power spots are purely for the individuals who seek the healing energy or ‘good luck’ associated with a location. It’s a familiar concept in Japanese culture and not too far from buying omamori good luck charms for fortune, health, and love at Shinto shrines throughout Japan. Many rural regions promote their charming shrines and alluring countrysides as being power spots, which can bring tourists and pilgrims to places forgotten by time.

5 Power Spots in and around Tokyo

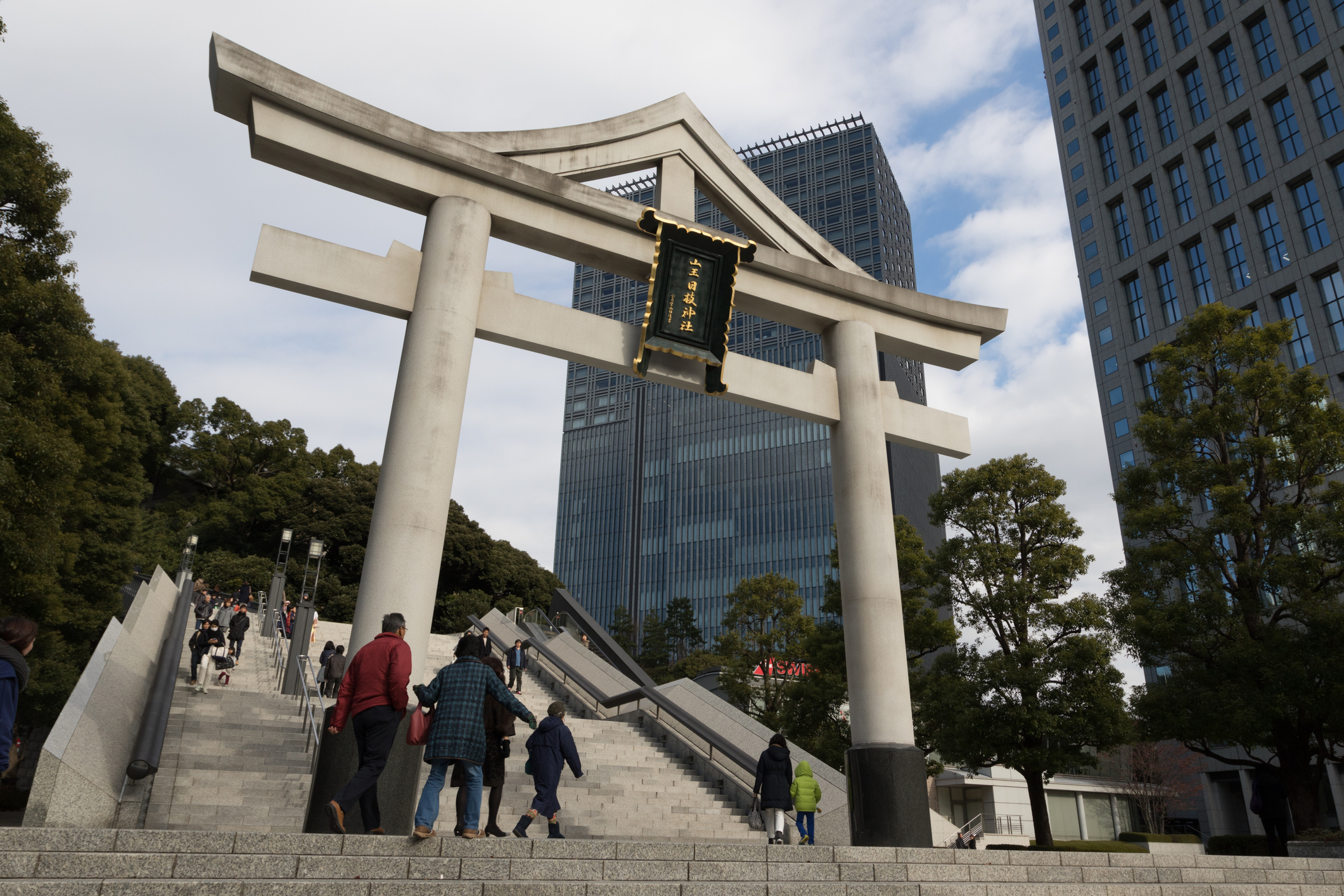

1. Hie Shrine

Hie Shrine is a Tokyo power spot, located on the top of a small hill in the heart of the Akasaka neighborhood. It’s most famous for its steep staircase of vermilion torii gates, and the monkey statues that dot the grounds of the 800-year old great hall.

The shrine is a power spot for those looking for luck in love. It’s a popular venue for Japanese weddings, and many couples who wish for a baby come to pat the statue of a mother monkey and her baby for good luck. When standing in the calm of the shrine’s grounds, even while being surrounded by skyscrapers, you’ll be able to feel the serene energy of the urban power spot.

2. Mount Takao

Just an hour from the bustle of Tokyo city center is Mount Takao, a holy mountain home to several power spots immersed in nature. The central power spot here is the main hall of the Mt. Takao Yakuo-in temple. It houses the deity Tengu, a supernatural creature that brings fortune and protects against disasters. Near the main hall is the bright red Aizen-do, a shrine and power spot that will bring luck in romance and marital harmony. The summit of Mount Takao is also a power spot, where you can see Mount Fuji on clear days—and if you hiked all the way to the summit, you’ll definitely feel powerful with a side of accomplishment. Reenergize by taking in the energy of the mountain, and by refueling with a bowl of Mount Takao’s famous soba!

3. Meiji Jingu

The Meiji Jingu is another power spot in central Tokyo that retains its tranquility even though it’s so close to flashy Harajuku and Shibuya. The Meiji Jingu Shrine houses the deities of Japan’s Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken, and visitors can take part in many Shinto traditions here like purifying one’s hands and mouth with water from the omizuya, and writing a wish on an ema wooden plaque.

The inner gardens (which costs ¥500 to enter), and specifically the Kiyomasa Well within it, are known to be a potent power spot overflowing with positive energy. The outer gardens also consist of many walking trails and lush greenery, making it a green oasis perfect for re-energizing.

4. Mount Fuji

Mt. Fuji is undoubtedly a mighty natural power spot—being in the presence of Japan’s holiest mountain and the spiritual heart of the country is a feeling you’ll always remember. The energy felt here doesn’t come from forests like other natural power spots, but from the mountain: feel the silent strength of the sleeping volcano as you peer down the caldera.

Visitors who summit Mt. Fuji and spend time at the highest point in Japan describe it as a transformative experience. At the summit are several mountain climbers’ huts and restaurants, as well as Okumiya shrine which embodies the holiness of Mount Fuji. Being so close to the gods here makes it a great place to have your wishes and prayers be heard.

5. Toshogu Shrine in Nikko

The Toshogu Shrine in Nikko is another power spot in Japan, and the massive shrine complex is declared a Unesco World Heritage site. It was built in 1617 to enshrine the first shogun of the Tokugawa shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and is famous for its colorful carvings and intricate woodwork on the buildings. The paths and staircases found here follow the natural topography of the shrine’s grounds, creating a feeling of balance with nature. Because it’s a popular tourist spot, be sure to stray to the quieter outskirts of the Toshogu Shrine to fully (and more quietly) experience the energy of this power spot.

Savvy Tip

Next to the Toshogu Shrine is another power spot at the Futasara-jinja, where visitors can follow a ritual of crawling through a hollowed-out tree trunk to receive purification.