New Year beginnings

New Year beginnings

The way Shinto and Buddhism complement each other is never more clearly seen than on the night of Dec. 31. Buddhism is other-worldly, concerned with individual salvation. Shinto is this-worldly, concerned with rites of passage and social well-being. At New Year the two religions come together like yin and yang, either side of midnight. Buddhism sees out the death of the old; Shinto celebrates the birth of the new.

In the dying minutes of the year, people line up at a Buddhist temple to hear the bell riing, or to ring it themselves. By tradition it is rung 108 times, once for every attachment that plagues the human condition. The atmosphere is solemn, and in the darkness the booming of the large bell carries with it a mournful feel that is carried for miles in all directions.

Once midnight strikes, by way of contrast, it’s time to head for a shrine to pick up arrow and amulets for protection through the coming year. The contemplative pre-midnight atmosphere is now replaced by a celebratory mood. Suddenly there are laughing voices, bright kimono, and gaudy lights. Stalls with wannabe yakuza sell candy floss and goldfish. Here all is jollity and smiles.

Arrows in red and white, celebratory colours of vitality, to ward off evil spirits throughout the coming year

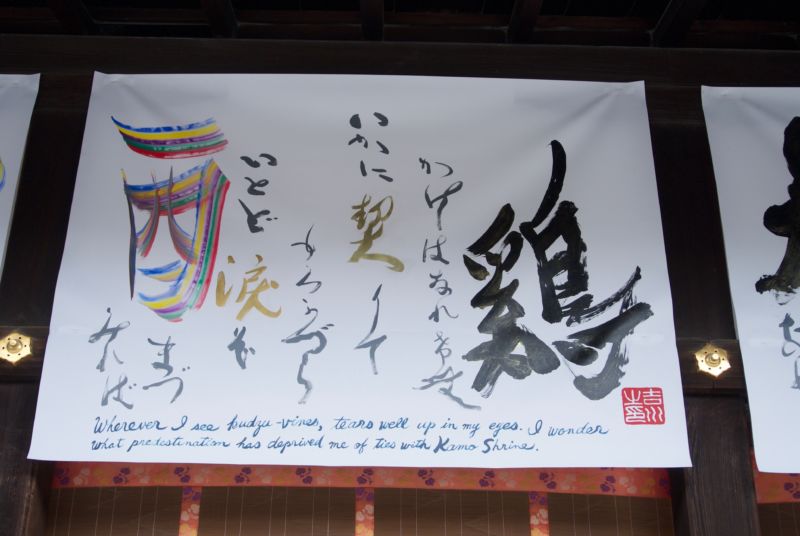

‘Akemashite omedeto’ (Congratulations on the New Year) is heard on every side, as people toss coins into offertory boxes over the heads of those in front. Hot saké is served spiced with ginger, while young women in kimono stand huddled over their fortune slips. With the blessing of the kami, the Year of the Rooster will surely be a good one.

Traditions and customs

New Year is a time of special food – osechi ryori – beautifully displayed in lunch boxes as only the Japanese can do. The custom originated with the Heian aristocracy, for whom New Year’s Day was one of the five seasonal festivals. Since it was taboo to cook during the three day event, food was prepared beforehand.

The New Year food is a feast for the eyes as much as the stomach, full of symbols and auspicious elements. There’s tai fish to signify ‘medetai’ (congratulations), and black beans as a wish for good health (mame can mean bean and health). Broiled fish cake (kamaboko) is laid out in red and white layers, traditional colours of celebration and suggestive of the rising sun.

Although the first shrine visit of the year (hatsumode) is supposed to be done within three days, people continue to pay respects for several days afterwards. Each year has its own auspicious direction, calculated by Chinese astrology, and the custom was to visit a shrine that lies in that direction (though few follow that these days). According to statistics, it seems the vast majority of Japanese visit a shrine at some point, though the percentage is skewed by the number of people who visit two or more shrines (for example their closest, their favourite shrine, and their ujigami).

Numbers are published and scanned with great interest, as if like GDP they reflect the well-being of the nation. Meiji Jingu invariably tops the rankings, with just over three million visitors (though one wonders who counts them). In the Kansai region Fushimi Inari comes top with over two and a half million – one reason why I’ve never dared visit it at New Year, though it’s a personal favourite.

From now on the New Year is all about firstness and freshness. There’s the first dream of the year, which if it is about Mt Fuji, a hawk or an aubergine (!) is held to be particularly auspicious. There’s the first snowfall, the first sign of spring, and the year’s first haiku…

A new year dawning:

First snow upon the mountains

Forming a fresh sheet

One interesting custom is the giving of money to children, known as toshidama. Toshi is the year, and dama is its soul or spirit – so it’s as if one is renewing the spirit of the year through the gift. No doubt the money helps give extra vigour to the young!

Decorations

The traditional New Year decoration is a length of shimenawa (sacred rice rope), festooned with ferns and the stem of a bitter orange, which is hung on the door (see pic at top). For Lafcadio Hearn, the shimenawa was the true ancient symbol of Shinto, other elements such as the ofuda and the torii having come in later. The fern is an evergreen and a symbol of the lifeforce, while the bitter orange is called daidai, which can also mean ‘generation to generation’. It indicates awareness of the ancestral continuity of the household.

It’s customary at this time of year to have steamed rice cake (mochi). This was traditionally done by pounding it by hand and eating fresh, but nowadays supermarkets are filled with plastic packages containing two circular rice cakes on top of each other surmounted by a bitter orange.

A pair of kagami mochi with daidai bitter orange and urajiro leaves

Rice is a symbol of fertility, and the mochicakes symbolise renewal of vitality through the eating of rice. Circular cakes are known as kagami mochi (mirror rice cakes). According to tradition, the sun-goddess Amaterasu presented her grandson with a circular mirror and told him to treat it as if it were her very self. It’s why mirrors are often used in shrines as the sacred ‘spirit-body’ of the kami. In this sense partaking of the round mochi is a kind of sacrament, the Japanese equivalent of communion.

The prime symbol of the New Year are the kadomatsu decorations seen in front of stores and large buildings. These can be grandiose affairs, consisting of three upright pieces of bamboo of differing length to represent the Taoist triad of heaven, earth and human.

Pine and plum branches complete the arrangement – pine not only as a symbol of constancy and vitality, but because the needles ward off evil spirits. The plum symbolises the promise of spring (before cherry blossom, the plum was Japan’s favourite tree for its early flowering amidst the austerity of winter.) Bamboo stands for persistence, a much admired trait among Japanese.

Kadomatsu in traditional style. Bamboo (for perseverance), pine (for evergreen), with nanten berries (red vitality), habotan (bad things become good) and plum (promise of spring) are the basic materials

Who’d have thought so much symbolism could be packed into a simple New Year decoration of natural elements? It’s indicative of just how important a role the New Year plays in Japan, and how much renewal, reinvigoration and revitalisation are written into the culture.

New Year beginnings

New Year beginnings