6) What difference do you see between practicing Shinto outside Japan compared to Shinto within Japan?

The biggest difference is definitely having the great numbers of foreign followers/attendees. Serving overseas automatically requires an English ability as well as the responsibility of satisfactory “Koto-age” which is to proactively clarify, discuss, explain the precepts of Ko-Shinto/Shinto, as well as the interpretation of mythology classics which has many ambiguous unclear portrayals.

As a Shinto clergy fluent in Japanese, providing the series of Norito liturgy lectures/workshops in English has been one of my significant roles assigned by Kami, as there aren’t fully reliable/accurate Norito resources available in English, unfortunately.

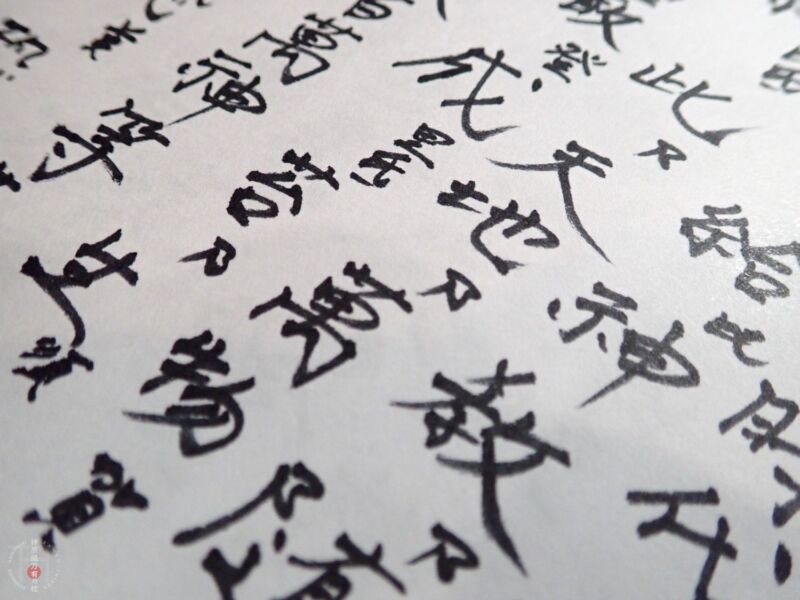

Norito is historically composed in Yamato-kotoba (words of Japanese origin; native Japanese words). It is very different from modern Japanese. For example, “newspaper” in Yamato-kotoba is「東西南北噂文 おちこちのうわさぶみ (Ochikochi-no-Uwasa-bumi, translating as Rumor composition from East to West to South to North」according to Kun-yomi (Japanese reading of Kanji). In modern Japanese it is「新聞 Shinbun: Newly heard」according to On-yomi phonetic Chinese reading of Kanji.

Traditional Norito also involves 万葉仮名 (Manyou-gana: early Japanese syllabary composed of Chinese characters used phonetically) and 歴史的仮名遣 (Rekishiteki-kana-dzukai:Historical Kana) which is mainly used by Shinto clergy when composing and reading Norito. 現代仮名遣い(Gendai-kana-dzukai: modern kana) is used by ordinary citizens.

Shinto prioritizes writing in Historical Kana and reading with 古語 (Kogo: Archaism) pronunciation. For example, Ookami おおかみ becomes Ohokami おほかみ.

Another example, 大祓詞(Great Purification Liturgy)is written as おほはらへのことばin 歴史的仮名遣, おおはらえのことば in 現代仮名遣い, yet both can be pronounced as Ooharae-no-kotoba or with a slight emphasis on “ほ”.

Some shrines write おほはらひのことば in historical Kana, or おおはらいのことば in modern kana, yet both can be pronounced “Ooharai-no-kotoba”.

According to linguistic expert Mr. Katsuji Iwahashi at Jinja-honcho, historical Kana and modern kana are not to be mixed, as it causes confusion especially for non-Japanese who do not know the difference between them and how to correctly read or pronounce them.

Therefore, the precise understanding of Norito requires expertise from Shinto clergy or language professionals to accurately introduce the way how to read and pronounce it, and to explain the depth of meaning in each word, as well as the complete translation of sentences.

Based on言霊 (Koto-tama/Koto-dama:spirit of word) spirituality from ancient Shinto time, correctly understanding and pronouncing each word has a remarkable effect in invoking the Koto-tama/Koto-dama. According to Hakke Shinto’s Nakagawa sensei, two significant elements in the ancient ceremony dating back to prehistoric Jomon period were Koto-tama and Oto-tama/Oto-dama (spirit of sound/instrument).

While serving overseas involves a large amount of work, I am truly honored and appreciative of this setting which Kami has assigned me, to cultivate the path to deliver the spirituality of Ko-Shinto/Shinto to the wider world. I am most humbled and also find joy in being the one to capture the similarities between Ko-Shinto/Shinto as well as with other spirituality/beliefs in the world, and sharing those experiences back with people in Japan. This experience has truly helped me to grow and refine myself as a Shinto priestess to serve the world.

7) Do you think in future it is possible for Shinto to spread in the US so that there are communities under legitimate Shinto shrines worshipping American kami with their own annual matsuri (Rei-Taisai) and form of rituals?

Yes, I do think it is quite possible for Shinto, especially Ko-Shinto to spread in the U.S. I have been actually witnessing that is already gradually happening, as there are remarkably many Americans who love Japanese culture and participate in Shinto ceremonies.

In this globalized era with the internet availability, people all around the world have way more opportunities to search what their spirits are looking for, compared to the past eras. In fact, that is how people leave the religions that they grew up with, and end up reaching me, as they have choices on their own now.

Japanese Anime widely spreading throughout the world and Anime conventions being operated almost at least once in a month somewhere in the U.S. (before Covid-19 pandemic) is also greatly contributing for Americans to be more exposed to Shinto, as many Anime portray Shinto whether they are accurately portrayed or not. Unconsciously or consciously, they are in touch with Shinto elements. It is a matter of time whether fast or slow.

As of “American Kami”, while I am not clearly understanding what exactly it means as it is sounding broad, but Ubusuna-no-kami of the local regional Kami of America can be definitely involved, such as Maryland Ubusuna-no-Ookami in my case, Hawaii-Ubusuna-no-kami for the case of Hawaii.

If you mean Native American deities, that can be also quite possible, as there are remarkable similarities between their (i.e. Hawaiian, Lakota, Alaskan, Hopi tribes) indigenous spirituality and Ko-Shinto/Shinto. However it definitely must be approved by them. Their tradition must be respected and preserved the way they are. I am simply answering this question whether it is possible or not. Most importantly, the anuual matsuri (Rei-Taisai) should be held at legitimate Shinto shrines or by licensed Shinto clergy.

If you mean “to apotheosize a historical person” in the U.S., like Sugawara-no-Michizane, Taira-no-Masakado, or Kodama Gentaro, it depends how people in American can tolerate the idea.

From the Shinto perspective, it is completely doable to conduct ceremonies for the occasions above, including making it an annual ceremony (Rei-Taisai) under legitimate Shinto shrines or licensed Shinto clergy. Shinto is very tolerant and flexible. It is a matter of whether Americans can be open to the ideas.